New Scientist reports that Uganda has been hit by a new outbreak of the mysterious ‘nodding syndrome’ or ‘nodding disease’ that seems to be an unknown neurological condition that only affects children.

New Scientist reports that Uganda has been hit by a new outbreak of the mysterious ‘nodding syndrome’ or ‘nodding disease’ that seems to be an unknown neurological condition that only affects children.

There is not much known about it but it seems to be a genuine neurological condition (and not an outbreak of ‘mass hysteria‘) that has devastated the lives of children in the region.

Affected children show a distinctive head nodding (although I would describe it more as lolling than nodding) and show delayed development neurologically and stunted growth physically. This apparently leads to malnutrition, injuries and reportedly, death.

The ‘head nodding’ is also reported to be prompted by food and eating, and by feeling cold, although these triggers are not as well verified.

If you want to see video of the symptoms the best is a seven minute piece from Global Health Frontline News although there’s also a good shorter report from Al Jazeera TV.

This brief Nature News article summarises what we know about it although from the neurological perspective there is good evidence from a preliminary studies that epilepsy and brain abnormalities are common in those with the condition.

There is some suspicion that it might be linked to infection with Onchocerca volvulus, the nematode parasite that causes river blindness, but early studies don’t show consistent results and ‘nodding syndrome’ isn’t prevalent in some other areas where the parasite is common.

One of the most mysterious aspects is why it only seems to affect children and currently there are no theories as to why.

Link to Nature News article on ‘nodding syndrome’.

Link to Global Health News TV report.

Link to open-access neurological study.

I’ve just found a sublime

I’ve just found a sublime

Nature has a fantastic

Nature has a fantastic  I’ve just stumbled across a

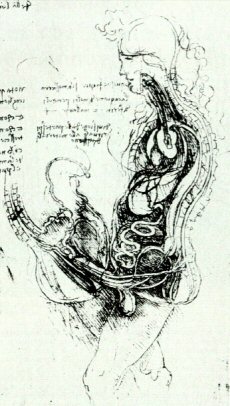

I’ve just stumbled across a  In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain.

In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain. The New York Times has a fascinating

The New York Times has a fascinating

A new

A new