How do you persuade somebody of the facts? Asking them to be fair, impartial and unbiased is not enough. To explain why, psychologist Tom Stafford analyses a classic scientific study.

One of the tricks our mind plays is to highlight evidence which confirms what we already believe. If we hear gossip about a rival we tend to think “I knew he was a nasty piece of work”; if we hear the same about our best friend we’re more likely to say “that’s just a rumour”. If you don’t trust the government then a change of policy is evidence of their weakness; if you do trust them the same change of policy can be evidence of their inherent reasonableness.

Once you learn about this mental habit – called confirmation bias – you start seeing it everywhere.

This matters when we want to make better decisions. Confirmation bias is OK as long as we’re right, but all too often we’re wrong, and we only pay attention to the deciding evidence when it’s too late.

How we should to protect our decisions from confirmation bias depends on why, psychologically, confirmation bias happens. There are, broadly, two possible accounts and a classic experiment from researchers at Princeton University pits the two against each other, revealing in the process a method for overcoming bias.

The first theory of confirmation bias is the most common. It’s the one you can detect in expressions like “You just believe what you want to believe”, or “He would say that, wouldn’t he?” or when the someone is accused of seeing things a particular way because of who they are, what their job is or which friends they have. Let’s call this the motivational theory of confirmation bias. It has a clear prescription for correcting the bias: change people’s motivations and they’ll stop being biased.

The alternative theory of confirmation bias is more subtle. The bias doesn’t exist because we only believe what we want to believe, but instead because we fail to ask the correct questions about new information and our own beliefs. This is a less neat theory, because there could be one hundred reasons why we reason incorrectly – everything from limitations of memory to inherent faults of logic. One possibility is that we simply have a blindspot in our imagination for the ways the world could be different from how we first assume it is. Under this account the way to correct confirmation bias is to give people a strategy to adjust their thinking. We assume people are already motivated to find out the truth, they just need a better method. Let’s call this the cognition theory of confirmation bias.

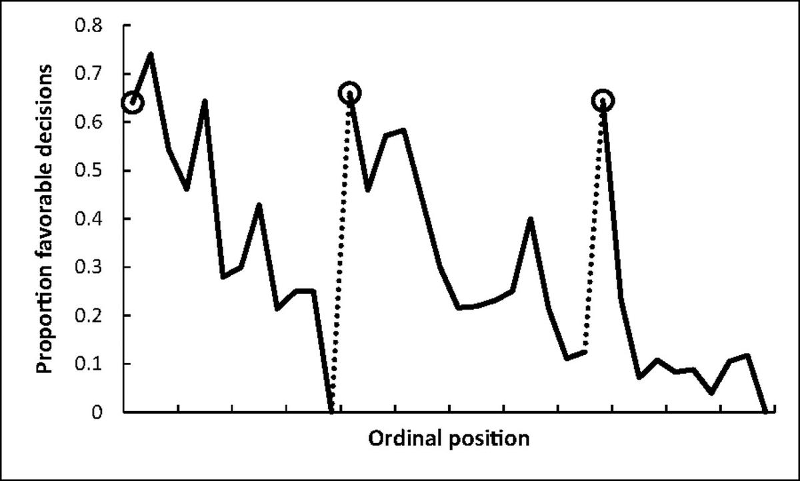

Thirty years ago, Charles Lord and colleagues published a classic experiment which pitted these two methods against each other. Their study used a persuasion experiment which previously had shown a kind of confirmation bias they called ‘biased assimilation’. Here, participants were recruited who had strong pro- or anti-death penalty views and were presented with evidence that seemed to support the continuation or abolition of the death penalty. Obviously, depending on what you already believe, this evidence is either confirmatory or disconfirmatory. Their original finding showed that the nature of the evidence didn’t matter as much as what people started out believing. Confirmatory evidence strengthened people’s views, as you’d expect, but so did disconfirmatory evidence. That’s right, anti-death penalty people became more anti-death penalty when shown pro-death penalty evidence (and vice versa). A clear example of biased reasoning.

For their follow-up study, Lord and colleagues re-ran the biased assimilation experiment, but testing two types of instructions for assimilating evidence about the effectiveness of the death penalty as a deterrent for murder. The motivational instructions told participants to be “as objective and unbiased as possible”, to consider themselves “as a judge or juror asked to weigh all of the evidence in a fair and impartial manner”. The alternative, cognition-focused, instructions were silent on the desired outcome of the participants’ consideration, instead focusing only on the strategy to employ: “Ask yourself at each step whether you would have made the same high or low evaluations had exactly the same study produced results on the other side of the issue.” So, for example, if presented with a piece of research that suggested the death penalty lowered murder rates, the participants were asked to analyse the study’s methodology and imagine the results pointed the opposite way.

They called this the “consider the opposite” strategy, and the results were striking. Instructed to be fair and impartial, participants showed the exact same biases when weighing the evidence as in the original experiment. Pro-death penalty participants thought the evidence supported the death penalty. Anti-death penalty participants thought it supported abolition. Wanting to make unbiased decisions wasn’t enough. The “consider the opposite” participants, on the other hand, completely overcame the biased assimilation effect – they weren’t driven to rate the studies which agreed with their preconceptions as better than the ones that disagreed, and didn’t become more extreme in their views regardless of which evidence they read.

The finding is good news for our faith in human nature. It isn’t that we don’t want to discover the truth, at least in the microcosm of reasoning tested in the experiment. All people needed was a strategy which helped them overcome the natural human short-sightedness to alternatives.

The moral for making better decisions is clear: wanting to be fair and objective alone isn’t enough. What’s needed are practical methods for correcting our limited reasoning – and a major limitation is our imagination for how else things might be. If we’re lucky, someone else will point out these alternatives, but if we’re on our own we can still take advantage of crutches for the mind like the “consider the opposite” strategy.

This is my BBC Future column from last week. You can read the original here. My ebook For argument’s sake: Evidence that reason can change minds is out now.

One of the most commented-upon posts on this blog is this from 2009, ‘

One of the most commented-upon posts on this blog is this from 2009, ‘ Dorothy Bishop has an excellent post

Dorothy Bishop has an excellent post