The ‘Regrets of the Typical American’ have been analysed in a new study that not only looks at what US citizens regret most, but provides some clues for those wanting to know whether it is better to regret something you haven’t done, or regret something you have.

The research has just been published in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science and was carried out by psychologists Mike Morrison and Neal Roese who used random dialling to call people and survey them about a troubling regret.

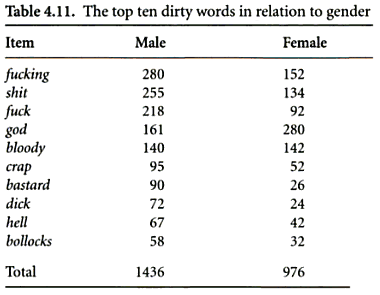

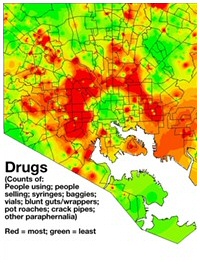

As blues singers have suggested for years, love tops the list (click for larger version):

Previous studies on regret have talked to college students who are probably not ideal for this sort of research as they tend to be quite young and, quite frankly, really haven’t fucked up enough to give a good idea of what the average person laments about their life.

This was the first study to survey a representative sample of all ages, incomes and education levels and although love topped the list, there were some interesting differences in the details.

Women, who tend to value social relationships more than men, have more regrets of love (romance, family) compared to men. Conversely, men were more likely to have work-related (career, education) regrets. Those who lack either higher education or a romantic relationship hold the most regrets in precisely these areas.

Americans with high levels of education had the most career-related regrets. Apparently, the more education obtained, the more acute may be the sensitivity to aspiration and fulfillment. Moreover, the youngest and least-educated people in our sample, who most likely possess the greatest capability of fixing their regrets, were indeed the most likely to provide fixable regrets.

The study also found that regrets about things you haven’t done were equally as common as regrets about things you have, no matter how old the person.

The difference between the two is often a psychological one, because we can frame the same regret either way – as regret about an action: ‘If only I had not dropped out of school’; or as a regret about an inaction: ‘If only I had stayed in school’.

Despite the fact that they are practically equivalent, regrets framed as laments about actions were more common and more intense than regrets about inactions, although inaction regrets tended to be longer lasting.

So the question of whether it is better to regret something you haven’t done than regret something you have, might actually be answerable for some people, but we still don’t know how much choice we have over adopting the different views of regrets or whether this is largely determined by the situation.

Link to summary of study ‘Regrets of the Typical American’.

Link to write-up on PhysOrg.

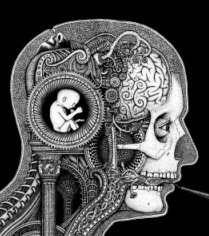

The neuroscience of suggestion and hypnosis are helping us to understand mysterious disorders where people are blind or paralysed with no apparent medical explanation, and may be useful in investigating altered states from diverse cultures – according to an engaging discussion in the monthly JNNP

The neuroscience of suggestion and hypnosis are helping us to understand mysterious disorders where people are blind or paralysed with no apparent medical explanation, and may be useful in investigating altered states from diverse cultures – according to an engaging discussion in the monthly JNNP  Those autotune-friendly science remix chaps Symphony of Science have just released a new

Those autotune-friendly science remix chaps Symphony of Science have just released a new

After almost any large scale disaster, you’ll hear reports that rescue workers, supplies and counsellors are being sent to the area – as if mental health professionals were as vital as food and shelter.

After almost any large scale disaster, you’ll hear reports that rescue workers, supplies and counsellors are being sent to the area – as if mental health professionals were as vital as food and shelter. The Guardian has an excellent ongoing

The Guardian has an excellent ongoing

The New York Times has a fantastic

The New York Times has a fantastic

Urbanite has a fascinating

Urbanite has a fascinating  BBC Radio 4’s Case Notes has an excellent

BBC Radio 4’s Case Notes has an excellent