Slate has got a great article that takes on the newly fashionable field of ‘neuromarketing’ and calls it out as an empty promise.

Slate has got a great article that takes on the newly fashionable field of ‘neuromarketing’ and calls it out as an empty promise.

The piece is written by neuroscientist Matt Wall who notes the upsurge in consumer EEG ‘brain wave’ technology has fuelled a boom in neuromarketing companies who claim that measuring the brain is the shining path to selling your product.

Because neuromarketing companies don’t provide the key details of the analysis techniques they use, it’s hard to evaluate them objectively. However, they seem to take a highly automated approach, essentially plugging the raw data into a black box of algorithms that spits out a neatly processed answer at the other end. Such an approach must involve making a large number of assumptions and some fancy-analysis footwork to make something coherent out of the poor-quality data.

In general the same applies to getting information out of a data set as to getting information out of a human: If you torture it long enough, it’ll tell you everything you want to know, but information extracted under torture is highly unreliable.

In addition, marketing-related studies are not well-suited to the kind of repetition that’s required to boost the useful signal and reduce noise; the same product or TV commercial can be presented only a few times before the participant becomes very bored indeed and therefore ceases to have any kind of meaningful reaction.

The article discusses why the current fad of EEG-based neuromarketing is scientifically unsound but despite the technical difficulties and theoretical incoherence of the field, it would all become irrelevant with one simple demonstration: a measure of the brain that could predict buyer preference better than behavioural or psychological measures.

Until now, no-one has shown this. In other words, no-one, nowhere, has shown that a ‘neuromarketing’ approach adds anything to what can be done by a standard marketing approach.

I’m all for neuromarketing research but until you can come up with the goods as a commercial product, you’re selling hot air.

There is one area that neuromarketing companies excel at though – marketing themselves. Considering a complete lack of data for their benefits, they pull in millions of dollars a year from advertising contracts.

Now that is effective marketing.

Link to Slate article ‘What Are Neuromarketers Really Selling?’

The Journal of Neuroscience has a surprising

The Journal of Neuroscience has a surprising

I’ve got an

I’ve got an  Spiegel Online has an excellent

Spiegel Online has an excellent

I’ve got an

I’ve got an

I’ve written a

I’ve written a  Two neuroscience projects have been earmarked for billion dollar funding by Europe and the US government but little has been said about what the projects will achieve. Here’s what we know.

Two neuroscience projects have been earmarked for billion dollar funding by Europe and the US government but little has been said about what the projects will achieve. Here’s what we know.

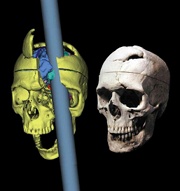

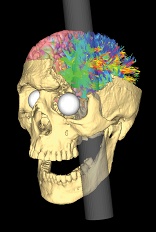

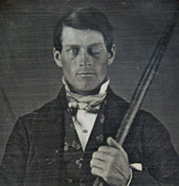

A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed.

A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed. A fascinating

A fascinating