The New York Times has an excerpt of a book that claims to expose one of the most famous psychiatric cases in popular culture as a fraud.

The New York Times has an excerpt of a book that claims to expose one of the most famous psychiatric cases in popular culture as a fraud.

Based on an analysis of previously locked archives the book suggests that the patient at the centre of the ‘Sybil’ case of ‘multiple personality disorder’ was, in fact, faking and admitted so to her psychiatrist.

The diagnosis, now named dissociative identity disorder, is controversial because the idea that someone can genuinely have several ‘personalities’ inside a single body has not been well verified and diagnoses seemed to boom after the concept became well-known.

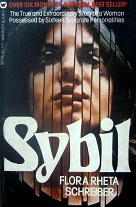

This particular case became well known because it was written up as a best-selling 1973 book and was later turned into successful film of the same name.

The book and the film are though to have been key in the shaping the concept of the diagnosis and making it popular during the late 70s and 80s.

However, detective work by author Debbie Nathan has seemed to uncover medical notes that suggest the psychiatrist at the centre of the case, Cornelia Wilbur, may have known that his patient had admitted to faking for some time.

One may afternoon in 1958, Mason walked into Wilbur’s office carrying a typed letter that ran to four pages. It began with Mason admitting that she was “none of the things I have pretended to be.

“I am not going to tell you there isn’t anything wrong,” the letter continued. “But it is not what I have led you to believe. . . . I do not have any multiple personalities. . . . I do not even have a ‘double.’ . . . I am all of them. I have been essentially lying.”

Before coming to New York, she wrote, she never pretended to have multiple personalities. As for her tales about “fugue” trips to Philadelphia, they were lies, too. Mason knew she had a problem. She “very, very, very much” wanted Wilbur’s help. To identify her real trouble and deal with it honestly, Mason wrote, she and Wilbur needed to stop demonizing her mother. It was true that she had been anxious and overly protective. But the “extreme things” — the rapes with the flashlights and bottles — were as fictional as the soap operas that she and her mother listened to on the radio. Her descriptions of gothic tortures “just sort of rolled out from somewhere, and once I had started and found you were interested, I continued. . . . Under pentothal,” Mason added, “I am much more original.”

Link to excerpt of book in the New York Times.

I read it a little differently, but no less disconcertingly. It seemed to me that the psychiatrist was using the patient both voyeuristically and as career fodder. The manipulation and deceit appeared to be bidirectional.

Different times, but how did DID become advanced and recognized in psychiatry without transparent peer review, critical analysis and plain vanilla evidence? Where is professional skepticism?

The difference between therapy and hucksterism isn’t evident here. At what point does psychiatry lose its privilege to call itself a medical specialty when it repeatedly breaks the social contract?

I’m pretty sure Cornelia would be a her, not a him as you have in your abstract when you say “his patient”. I agree with the person who commented above that there appeared to be bidirectional manipulation/deceit going on based on the description in the NYT article. The whole story always sounded unreal in some ways to me and I agree that somewhere there should have been some kind of professional review and skepticism brought to bear. But the truer version of the story also gets at how manipulable “identity” can be.

Cornelia Burwell Wilbur, M.D., graduated from the University of Michigan in 1930, was one of eight women medical college graduates in 1939 and the first female medical student extern at Kalamazoo State Hospital, and therefore definitely “her.”

Ah, but maybe the personality that admitted she was making it up, was just another one of the multiple personalities!

That’s the great thing about the hypothesis of multiple personalities. No matter what happens, it’s still an explanation.

As a clinical psychologist I remained skeptical with regard to DID partly because because those patients I carefully evaluated seemed very interested in receiving disability payments. And I found that these patients seemed well aware of the different personalities they reported. In other words, there was no genuine dissociation.

Interesting — as you note, not many clinicians will be surprised that this isn’t real.

I’m not sure if this is intentionally misleading or whether vaughanbell just didn’t read to the end of the NYT piece. Mason later disassociated herself from the letter quoted here, so this isn’t the final word. In fact, she said “someone” had written and delivered it. So in some identity states, she didn’t buy this diagnosis or even her own presentation of herself, and in other identity states, she did.

If by DID or MPD being “not real,” you want to say that there aren’t tiny separate people inside these human bodies, then fine, it’s “not real.” But what people experience is something else.

We all know what it’s like to feel like almost a different person in different contexts, to have slightly different identities as parent, worker, citizen, child. In some people, these different identity states are experienced as more bounded, more dissociated. The phenomenon is not like Sybill or The Three Faces of Eve, but it’s not completely nonexistent, either.

I’m not a shrink; I just have been close to someone who is put together this way, and through her, I have met others. The whole thing is confusing, to them and to those close to them. I’m sure sometimes, it’s just a matter of suggestion from a clinician – but not always. There is more to know. It’s likely that there have been times, as in the Wilbur case, when a clinician pushed the diagnosis onto a patient. It’s also possible that Mason did experience what is called DID. It’s certainly the case that others have. Both clinician overstepping and client experience of ptsd and dissociation could be true at the same time.

People in contexts like this blog should be much less confident that they know what they’re talking about.

I love how everyone is jumping on a mentally disturbed individual stating they are not “that” disturbed as proof that the individual was not “that” disturbed. Says more about those that were just looking to confirm THEIR bias than it actually sheds light on the factual basis of the story ;-).