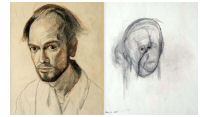

Wired Magazine has an article on a curious condition known as prosopagnosia where affected individuals cannot recognise people by their faces, despite being able to recognise and distinguish everyday objects with little trouble.

Wired Magazine has an article on a curious condition known as prosopagnosia where affected individuals cannot recognise people by their faces, despite being able to recognise and distinguish everyday objects with little trouble.

Until recently, it was thought that the condition only arose after brain injury – usually because of damage to an area of the brain known as the fusiform gyrus. This area is known to be heavily involved in face recognition.

It has more recently been reported as an inherited form, suggesting that some people are simply born with particularly bad face recognition skills.

The article looks at the work of neuropsychologist Dr Bradley Duchaine who is investigating the psychology and neuroscience of face recognition impairment, and discusses the experience of several people who have the condition.

One of the people is Bill Choisser, who created ‘Face Blind!‘, one of the first and longest-running prosopagnosia websites on the net.

A particularly striking feature of his site is a self-published book which is an in-depth discussion of the condition and its effects.

Link to Wired article ‘Face Blind’.

Link to Bradley Duchaine’s page with copies of his scientific papers.

Link to Bill Choisser’s website on prosopagnosia.

There’s an interesting (and actually quite funny)

There’s an interesting (and actually quite funny)

The cover story on yesterday’s The Independent on Sunday had a special report on eating disorders. The report is in several sections and covers the rising prevalence of eating disorders and the experience of people who have anorexia or bulimia.

The cover story on yesterday’s The Independent on Sunday had a special report on eating disorders. The report is in several sections and covers the rising prevalence of eating disorders and the experience of people who have anorexia or bulimia. Neurofuture is back with a bang after a late-summer sabbatical and has

Neurofuture is back with a bang after a late-summer sabbatical and has  This week’s Nature has a fascinating and freely-accessible review (

This week’s Nature has a fascinating and freely-accessible review (

I just discovered from The Neurophilosopher’s

I just discovered from The Neurophilosopher’s

Surely this isn’t news? BBC News is

Surely this isn’t news? BBC News is  The UK government have launched a campaign to warn 11-15 year-olds about the dangers of cannabis, using an ironic and lighthearted

The UK government have launched a campaign to warn 11-15 year-olds about the dangers of cannabis, using an ironic and lighthearted