Aeon magazine has an excellent article about how a study on the adoption of Romanian orphans has helped us understand the importance of early-life affection for brain development.

Aeon magazine has an excellent article about how a study on the adoption of Romanian orphans has helped us understand the importance of early-life affection for brain development.

It tracks the story of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), a US-based study that was inspired by seeing the appalling living conditions of orphans from the Ceausescu regime era.

Many were left with virtually no human interaction, were often poorly fed, in poor health and sometimes seemed to be cognitively impaired.

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project completed a randomised controlled trial to show that adoption not only improved physical health but also improved brain function – demonstrating the importance of human contact for healthy brain development.

It’s a moving article that really gets into the importance of early development but it gives an curious impression of what inspired the studies.

It suggests that in 1999, when the study was first launched, previous studies on the negative neurodevelopmental effects of depriving young animals of maternal affection provided the basis for thinking that this is what might be happening in the Romanian orphans.

This is certainly one line of thinking. The experiments of serial monkey abuser Harry Harlow often pop up in these discussions, despite the fact that the effect of early care and affection on healthy emotional development has been known since antiquity and was demonstrated by John Bowlby’s studies on World War II evacuee children years before.

But in the case of Romanian orphans, one of the most important sources of information was not animal studies, but studies already done on the effects of adoption on brain development in Romanian Orphans – of which the first study was published a year earlier, in 1998.

These studies were led by child psychiatrist Michael Rutter who had revisited Bowlby’s ideas and thought that while broadly accurate they were probably too strong in their predictions and that development could be improved for many.

When the Ceausescu regime fell and the plight of the orphanages became clear, many families from across Europe adopted orphans. Rutter compared children who had been taken up by UK families and compared them on what age they were adopted.

The studies found that the length of emotional deprivation was associated with smaller head size (reflecting brain development), lowered IQ, and increased mental heath problems, even when the effects of poor nutrition were controlled for.

One of the difficulties is that the results may not have been comparable to the effects of adoption by Romanian families – which, for example, remains a country with a more limited healthcare system.

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project were the first to run a randomised controlled trial of adoption – literally, an experiment to compare adopting children versus institutional care – to conclusively demonstrate the benefits.

Needless to say, it was an ethically charged project, and the Aeon article discusses the challenges that it raised.

Link to Aeon article ‘Detachment’.

Philosopher

Philosopher  One of the computational linguists who applied forensic text analysis to JK Rowling’s books to uncover her as the author of

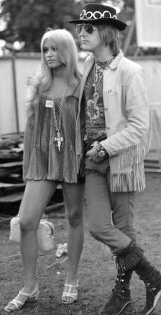

One of the computational linguists who applied forensic text analysis to JK Rowling’s books to uncover her as the author of  The Groupies is a remarkable

The Groupies is a remarkable  Nature has an

Nature has an

Funny or Die is supposedly a comedy site but they seem to have a brief

Funny or Die is supposedly a comedy site but they seem to have a brief  The late Pope John Paul II is to be

The late Pope John Paul II is to be