Decades old research into how memory works should have revolutionised University teaching. It didn’t.

If you’re a student, what I’m about to tell you will let you change how you study so that it is more effective, more enjoyable and easier. If you work at a University, you – like me – should hang your head in shame that we’ve known this for decades but still teach the way we do.

There’s a dangerous idea in education that students are receptacles, and teachers are responsible for providing content that fills them up. This model encourages us to test students by the amount of content they can regurgitate, to focus overly on statements rather than skills in assessment and on syllabuses rather than values in teaching. It also encourages us to believe that we should try and learn things by trying to remember them. Sounds plausible, perhaps, but there’s a problem. Research into the psychology of memory shows that intention to remember is a very minor factor in whether you remember something or not. Far more important than whether you want to remember something is how you think about the material when you encounter it.

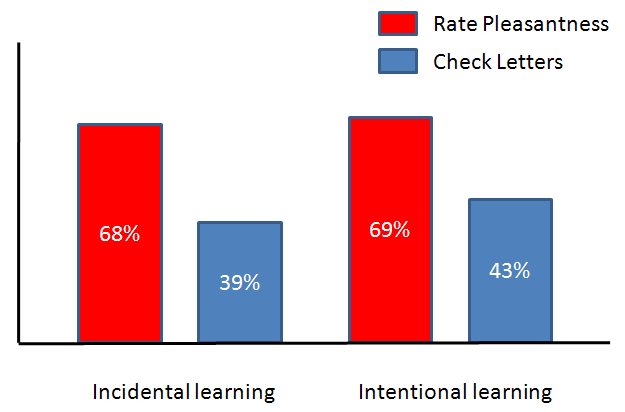

A classic experiment by Hyde and Jenkins (1973) illustrates this. These researchers gave participants lists of words, which they later tested recall of, as their memory items. To affect their thinking about the words, half the participants were told to rate the pleasantness of each word, and half were told to check if the word contained the letters ‘e’ or ‘g’. This manipulation was designed to affect ‘depth of processing’. The participants in the rating-pleasantness condition had to think about what the word meant, and relate it to themselves (how they felt about it) – “deep processing”. Participants in the letter-checking condition just had to look at the shape of the letters, they didn’t even have to read the word if they didn’t want to – “shallow processing”. The second, independent, manipulation concerned whether participants knew that they would be tested later on the words. Half of each group were told this – the “intentional learning” condition – and half weren’t told, the test would come as a surprise – the “incidental learning” condition.

I’ve made a graph so you can see the effects of these two manipulations

As you can see, there isn’t much difference between the intentional and incidental learning conditions. Whether or not a participant wanted to remember the words didn’t affect how many words they remembered. Instead, the major effect is due to how participants thought about the words when they encountered them. Participants who thought deeply about the words remembered nearly twice as many as participants who only thought shallowly about the words, regardless of whether they intended to remember them or not.

The implications for how we teach and learn should be clear. Wanting to remember, or telling people to remember, isn’t effective. If you want to remember something you need to think about it deeply. This means you need to think about what you are trying to remember means, both in relationship to other material you are trying to learn, and to yourself. Other research in memory has shown the importance of schema – memory patterns and structures – for recall. As teachers, we try and organise our course material for the convenience of students, to best help them understand it. Unfortunately, this organisation – the schema – for the material then becomes part of the assessment and something which students try to remember. What this research suggests is that, merely in terms of remembering, it would be more effective for students to come up with their own organisation for course material.

If you are a student the implication of this study and those like it is clear : don’t stress yourself with revision where you read and re-read textbooks and course notes. You’ll remember better (and understand much better) if you try and re-organise the material you’ve been given in your own way.

If you are a teacher, like me, then this research raises some disturbing questions. At a University the main form of teaching we do is the lecture, which puts the student in a passive role and, essentially, asks them to “remember this” – an instruction we know to be ineffective. Instead, we should be thinking hard, always, about how to create teaching experiences in which students are more active, and about creating courses in which students are permitted and encouraged to come up with their own organisation of material, rather than just forced to regurgitate ours.

Reference: Hyde, T. S., & Jenkins, J. J. (1973). Recall for words as a function of semantic, graphic, and syntactic orienting tasks. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12(5), 471–480.

Now available in Italian Insegnare ed apprendere in modo efficace (thanks Giuliana!)

Very suspicious that there’s almost no improvement from incidental to intentional. Tell me to examine a phone number, and there’s a 0% chance I’ll remember it later. Tell me to memorize it, and make it worth it for me, and there’s a 90% chance I’ll do it.

The deal is that usually when you inform people of a future learning test they probably change the strategy with which they approach the material. This study controlled for that by holding a particular strategy constant across the two levels of the other independent variable (knowledge of a future test) and it showed that, when using a particular strategy, awareness of a future test won’t change the efficiency of the strategy.

Tell you neither, and instead, have you call that number multiple times, for something you want and you will retain it much longer. It will be conditioned in you. Even if I tell you to memorize it, you will, for a short period of time. If you don’t actually dial it, you are more likely forget. We remember what we do, a lot more than what we hear or see.

Phone numbers are special situations. 7 bits is generally considered the limit of short term recall. But, if suspicions and intuitions were generally accurate, there would be no purpose to science and systematic study.

well your brain is using the rule of 7’s to remember that 7 digit number when you repeat it in your head over and over. this won’t work with a list of items longer than 7-9 or so

This seems to support more of an inside-out approach to educating rather than the traditional outside-in approach. This makes sense. It is more efficient. On the other hand, there might be instances when an individual could benefit from meta organizational skills, learning how to learn. Not a focus on content, but on process.

When I was a student, I’ve found out that if I prepared cheat sheets for a written exam, more often than not I didn’t have to use them at all – the process of condensing the knowledge to its essentials so that they fit into the teeny tiny sheets has committed it to my memory.

I am writing exam in a weeks time, so guess what I am going to try it and let you know how it go’s. It makes so much sense, acutely excited for my preproration. Will let you guys know how it go’s with the study method:-)

I second hat_eater’s comment. Making crib sheets at university mysteriously improved my memory recall well beyond simply reading over the material, and almost always to the point where I didn’t need the crib sheet afterwards!

I think the reason crib sheets / cheat sheets work is exactly because of the reasons outlined in the article – you only have two sides of paper, hence you need to heavily summarise the information and, more importantly, organise it onto the paper in a manner that aids its use during an exam.

(It’s still my favourite way of reading technical, software engineering manuals!)

“and about creating courses in which students are permitted and encouraged to come up with their own organisation of material, rather than just forced to regurgiate ours.”

As a student, thank you for this. It’s the first time I’ve seen such a statement on learning pedagogy.

Good article Tom,

My PhD supervisor always talks about the need to get students to engage in deep learning, i.e. understanding what things actually mean, rather than just engaging in shallow learning, i.e. regurgitating knowledge in an exam. The only time he advocates shallow learning is if a student is really struggling in a particular area which they need to pass, e.g. statistics, although even in this case an initial approach of deep learning would be better.

I try to emphasize this approach to my 1st years as well, getting them to paraphrase what I’ve taught them in plain english first, then re-expressing it using the proper psychological terminology.

Another aspect of psychology crucial to education which is not emphasised is attribution with regards to success. Students who attribute their success to effort tend to reinforce their effort in studying, and so go on to do better in the future by trying harder. In contrast, students who attribute their success to intelligence or ability, tend to work either less hard, or no harder than they normally do. And of course, praising someone for their intelligence doesn’t reinforce or increase intelligence like praising someone for hard work does. This is a very simple but vital finding, which we should be teaching children from a young age (and certainly teaching 1st year psychologists!).

I agree with both hat_eater and Asim – when I was in university, I always studied for exams by writing out cheat sheets on the course materials. This helped me get down to the very basic principles of each concept, as well as helped me really reflect on how each concept related to any other.

Most lecturers and teachers I’ve ever encountered have intended to set work as well as give lectures.

I’d be interested to know how often courses at schools, colleges or universities consist only of lectures and exams with no exercises, further reading, essays or assignments.

Arousal, priming and meaning. Repeat.

Yes, researchers and education experts have known this for decades.

But how are most faculty taught now to teach? Not at all – they simply do their best to replicate how they were taught.

I dunno about “cheat sheets,” but what always worked for me, was to take notes on the text, as long as I forced myself to put it in “my own words,” as opposed to just re-typing what was in the textbook. I quickly got a good system down of following the outline of the textbooks, bolding words that I was defining, that kind of thing.

But yeah, I often learned the material so well that way, that I didn’t need to read the notes after I’d written them!

This seems to support more of an inside-out approach to educating rather than the traditional outside-in approach. This makes sense. It is more efficient. On the other hand, there might be instances when an individual could benefit from meta organizational skills, learning how to learn. Not a focus on content, but on process.

What are thoughts on how this method of learning compares to repetition/practiced rehearsal? As a former teacher, I am fond of the idea of having students think deeply, process and make connections. But now as a late-starting medical student I understand again how hard it is to think deeply and synthesize tremendous volumes of novel material. While some information can be organized into concepts, many things simply need to be committed to memory just to have the scaffold for more conceptual themes (like learning the characters of a new language before writing words and sentences.) Rehearsal/flash cards seem to work best for those kinds of free floating ideas.

Well, you always have to start from something. If the material is unlike anything you’ve ever seen before, you obviously cannot make meaningful associations. But, as far as I recall, processing the semantic content of the material and making connections that make sense to you, as opposed to repeating the material and creating memories on a phonetic basis, is far more efficient.

Just think of memorizing strings of numbers. If you can recognize meaning in them, you’ll probably have to see them only once, whereas if they make no sense to you, you have the option of repeating them, OR I guess you can force meaning upon them – get creative! 🙂

Um, the graph looks mislabeled. According to the text, the students who examined letters remember more, but in the graph, it’s the other way around.

The graph is right. And the text, as far as I can see. In which bit does it say that there was superior recall from the people who examined letters?

Actually, while we are here and it is now I do have a confession about the graph – no y-axis label (o mea culpa!). It should, of course, be “percentage recall”

The Levels-of-processing approach is to vague to apply to educational settings like you are suggesting. It may work well with pleasantness ratings but can you imagine asking students to rate the pleasantness of the serial position effect? or the capacity of short-term memory?

Fortunately, there is something much easier to incorporate, but you glossed right over it — the benefits of retrieval practise (aka the testing effect). Testing enhances long term retention, and all that’s required is that there are frequent tests.

Karpicke, J.D., & Roediger, H.L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319, 966-968

Nice post; a good intro to levels of processing.

The criticism of lecturing stings a bit, though. (How was I ever able to remember anything from university?)

Looking forward to your follow-up post on how to replace those bad old lectures with “active learning.”

There *is* a follow-up post coming, right?

@Tyler – levels of processing too vague to apply to education? I think you’ve given up too early on the ambition to help students think deeply about the material they are learning

@kloepelm – not just a follow-up post, but a follow up paper! Watch this space. For an earlier attempt at developing active learning see this http://www.abrg.group.shef.ac.uk/show_pub.php?id=11

Obviously there will be times when a lecture is useful – scaffolding students’ understanding of an area, providing a structure into which topics fit, or a good example of their intregration – the point of this post is just that lectures are no more the best tool for teaching than hammers are the best tools for building.

I think the reason that cheat sheets and writing things down in your own words works is simply because the act of writing itself imprints things on your brain and memory. The body and the mind are connected, and when you write you are making a connection between the two. However, writing on a computer does not seem to have the same effect.

Mike, interesting idea, to compare handwriting to computer notes. Is it already done?.

Hello. I like this article. I would like just to say that I can compare two different ways of learning and also maybe teaching. I normaly study in Czech Republic but now I study in Finland. In Czech we usualy get materials and we can just highlight what we consider as important in the materials. Here in Finland we get only some basic structure in Powerpoint (which is used during lessons) and questions for exams. Then we have to look up all the answers on our own. Of course it takes longer time but I think I remember more and sometimes I escape somewhere into related topic in the area of question and I enjoy the question finally.

I completely agree! I’m studying to become a teacher and also majoring in psychology. What’s interesting is that the classes I do the best in are the ones where the professor randomly calls on students to answer questions. As scary is that is sometimes, it allows students to be active and challenges them to think. I actually learned about this study in my Cognitive Psychology class, and to no surprise, the professor of that class always asks us what the material we just learns means to us. Needless to say, i’ve retained almost everything we’ve learned so far (which is very helpful as finals are next week)! Great article!

So glad this is brought up with such clarity. It’s obvious the effort to shift teaching methods to complement learning modes will require lots of energy. I recently interviewed Win Wenger and learned that 300 upstate NY students successfully “learn” 4 years of academic material in one year. They are using techniques pioneered by Win (look-up Project Renaissance), which essentially increase intelligence by including more of what students already know and by using student-based feedback, an essential process for meaningful learning. BTW, Mind Hacks is a supreme connection!

Perhaps I wasn’t reading carefully enough or what-not. But I have realised that this article doesn’t actually teach me HOW to study more effectively. It only showed me the statistics of different ways of learning. I want to know HOW

It is not amazing that every one’s level of deep processing and memorization is different. but where there intentional processing and having more importance there are more chances that every ones’ level of processing and memorization may become relativily equal.

I have been having troubles with social studies but thanks to you I got a A+. Thank you very much sir you have helped me very much and I will look for this.

Signed:Jacob Richard Davis

Age 11 city:Warroad Minnesota

Thanks

This will probably never be seen but here I go… I am currently a second semester senior in college about to go off to medical school. I personally have always had a love of learning, something that has been severely damaged over the years due to school. I also have been teaching SI classes since my sophomore year. (which for those of you who are up to date on advances in college education, SI stands for Supplemental Instruction, and these sessions are usually taught by students who have performed extremely well in the respective class and taught with techniques based upon the research in this article). I have taught 8 semesters of SI (including the current semester) and was so successful, that I became the first ever SI leader at my college to teach SI over the summer, and actually taught two classes thereby making it a full time job (40+ hrs/wk) all summer long. On a scale of very traditional teaching to very nontraditional teaching (based on this type of research), I have dealt with professors at both extremes and everything in between and from my experience there is something that needs to be SERIOUSLY addressed before colleges move away from their traditional teaching. For one, this “new method” is based on the assumption that students want to learn. Unfortunately, myself and many students like me, who maybe originally desired knowledge have been so beaten down by our institutions that all we care about know is our GPA because we believe that it equals money down the road and that we will never reach our aspirations unless we do perfect in our classes. I have a 3.9+ (out of 4.0) GPA, tons of credentials on my resume, and a type A personality but I still stressed day in and day out if I would make it into medical school. Students don’t want to learn the material, they want the material feed to them so they can ace the test. I think professors have blown this off too much and this issue needs a solution.