Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

The Guardian asks whether the internet encourages insidious and bullying behaviour? Well, does it, punk?

We typically don’t remember our early years but it turns out this amnesia develops over time, as a brilliant piece on ‘The shifting boundary of childhood amnesia‘ at Psychology Today recounts.

BBC Radio 4 had a good documentary on the influence of Freud on British culture. Only three more days to listen – annoying, I know.

There’s a brilliant post on consciousness, mental time travel and the brain over at the consistently excellent Neuroskeptic.

BBC News report on the switch to short-acting barbiturate pentobarbital for the death penalty in the US. “a sedative typically used to put down animals” says the BBC, although they don’t mention it’s also used in the acute treatment of epileptic seizures.

Science News covers a new study on the intriguing but not very pleasant hallucinogen salvia divinorum.

Dan Ariely’s blog Irrationally Yours looks at how perception of value relates to worker effort not results.

The woman with no fear (and no amygdalae). Coverage from Not Exactly Rocket Science and Neurophilosophy outdid all the mainstreams.

The New York Times has a Bayesian take on Julian Assange: “…from the standpoint of Bayesian reasoning, to think we can separate out the merits of the charges from their political motivations.”

Footage of Freud and psychoanalysis – from the 1940s. Advances in the History of Psychology finds two archive gems.

The Guardian science blog covers an interesting study that tested whether sleep deprivation can prevent post-traumatic stress disorder.

For the first time, marijuana use is more common in American kids than cigarette smoking. The excellent Addiction Inbox has a great write-up.

Macleans has a great piece on fashionable paranoias. Nothing to fear but wifi and fluoride.

There’s an excellent analysis of how top flight science journals handle studies on language over at Child’s Play. In brief, they don’t.

The New York Times has a long but rewarding piece on ‘embodied cognition‘ by philosopher of mind Andy Clark.

The top 10 psychology studies of 2011 have been selected with excellent taste by Neuronarrative.

You all know the excellent Brain Ethics blog has just been relaunched right? New pieces on how to teach neuromarketing and whether genes make up your mind.

The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law has a thoughtful piece by a psychiatrist reflecting on Foucault, forensic psychiatry, and committing patients to hospital against their will.

We believe we have more free will than other people. Neurotic Physiology feels compelled to cover this fascinating new study.

The Guardian science blog has an eye-opening piece about the discrepancy between which childhood neurological disorders get the funding and which are most common.

The way in which data is collected for a psychology study affects the sort of people who volunteer. The BPS Research Digest covers the subtle effects of research design.

New Scientist has the best books of 2010 as chosen by neuroscience Steven Rose.

Psychologically inclined filmmaker Adam Curtis finds a social history gem on his BBC blog The Medium and the Message: a 1969 British documentary on the office Christmas party.

Seed Magazine looks at the science of interconnectedness and understanding risk in a connected world.

Contrary to lay wisdom, high trusters were significantly better than low trusters were at detecting lies. Barking up the Wrong Tree covers a counter-intuitive study.

Cannibalism is a lot more common in human history than you’d guess and an intriguing

Cannibalism is a lot more common in human history than you’d guess and an intriguing  Ecstasy users often describe the high as feeling ‘loved up’ and

Ecstasy users often describe the high as feeling ‘loved up’ and

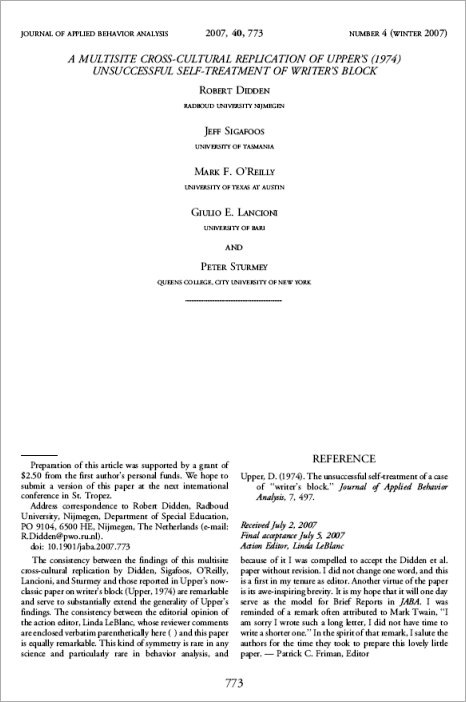

History of Psychology has just published a brief

History of Psychology has just published a brief  You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed.

You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed. The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated.

The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated. Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents.

Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents. The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”.

The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”. The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.

The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.

The Boston Globe has an excellent

The Boston Globe has an excellent  Edge has a fascinating

Edge has a fascinating

Pioneering neurosurgeon

Pioneering neurosurgeon