This is Part II of our interview with ethnobotanist and explorer Wade Davis where we discuss technology, culture and the slippery concept of human nature.

This is Part II of our interview with ethnobotanist and explorer Wade Davis where we discuss technology, culture and the slippery concept of human nature.

Davis kindly spoke to myself and science journalist Ana María Jaramillo while visiting Medellín’s excellent science museum Parque Explorer and in Part I we discussed altered states of consciousness and the use of psychedelic plants.

If you’re in Medellín, the science museum is shortly to host an exhibition curated by Davis, of photographs by the founding father of ethnobotany, Richard Evans Shultes.

Schultes travelled through then unexplored parts of the Amazon and studied the native peoples, their rituals and knowledge of the forest and was Davis’ professor and mentor.

Ana María: You wrote “Anthropology has long taught that whether a people’s mental potential goes into technical wizardry or unravelling the complex threads of memory inherent in a myth is merely a matter of cultural choice and orientation.” Do you think Western cultures have lost anything important with a greater focus on technical wizardry?

I’m no scholar of middle Europe but if you think of the moment that we elected to liberate ourselves from the tyranny of absolute faith, and that case, the tyranny of the church, the whole thrust of the Enlightenment was the power of the mind over the body of man. When Descartes said that ‘mind and matter is all that matters’ he thrust out all instincts for myth, mysticism and metaphor and basically, in a single gesture, devitalised Europe.

That idea that only human beings can be animate or the idea that a bird could have animus was ridiculed and dismissed as ridiculous. It was pretty clear that the way that we treat the Earth as simply a raw resource to be consumed at our pleasure comes directly out of that process of devitalising the Earth.

That really goes back to the revelations of genetics where geneticists have shown that we’re all cut from the same genetic cloth, that race is a complete fiction, that the human genetic endowment is a continuum. And the corollary of that is that if we all share the same raw intellectual capacity we all share the same human genes and so how the genes are expressed is a matter of cultural choice.

That’s really my whole work with National Geographic to go around the world looking at cultures that manifest the human genus in different ways. Whether that be a shaman learning to manipulate plants with such dexterity to create a preparation like ayuhuasca or the Polynesian navigator who, through a process of dead reckoning, was able to chart the open oceans centuries before the Europeans dared leave the protection of the coastline, or the Buddhist science of the mind with 2500 years of empirical observation on the nature of mind.

To me these are all just options that human beings have taken. In terms of the relationship to the natural world the classic opposition to our world view is the Aborigines of Australia. What’s fascinating when you look at their entire intellectual devotion is that it is not to improve upon anything. We embrace this cult of improvement which technological wizardry expressed and made this really remarkable world we live in, which I’m not denigrating.

My friend Andy Weil, even though he’ll speak of the value of alternative medicine, says that if you get your arm ripped off in a car accident you don’t want to be taken to a shaman. But the physical impact of our world view on the planet has been demonstrable and what I find interesting is that in these cultures that define the world as being alive – like in Andean Peru where people really do believe that they have a reciprocal obligation to the Earth and the Earth in turn has reciprocal obligations to people. That doesn’t mean that the people of the Andes didn’t cut down the forests – they did – but in general that world has a much more gentle impact on the landscape than modernity has had.

And with the Aborigines it’s fascinating because they didn’t only not embrace the cult of progress but they embraced a world view that denied progress. Their who purpose in life was to not improve on anything – to do the ritual gestures necessary to maintain the world exactly as it was at the time of its origins and that’s a profoundly conservative way of thinking but it had real consequences. As a result – yes they didn’t develop a sophisticated material culture – but they didn’t create climate change either.

I don’t think any of this is about saying who’s right and who’s wrong but it’s just fascinating to recognise that there are different options and these other cultures aren’t failed attempts at being us but they’re unique answers to a fundamental question – what does it mean to be human and alive?

When people answer that question, they do so in 7,000 languages. The problem comes along through cultural myopia, which all cultures tend to have but with our unique power we are causing so many of these world views to be lost.

Vaughan: One of the things that anthropology is constantly doing is defying our expectation of what it is to be human. I’m wondering how much you believe in a common humanity?

Genetics shows that we’re all cut from the same genetic cloth, and, as I said, social anthropology shows that we all have the same adaptive imperatives. That’s what I find so cool about culture. Every culture has to deal with death, every culture deals with procreation, coupling or whatever, but within that communality there’s this amazing set of possibilities and so many unique outcomes.

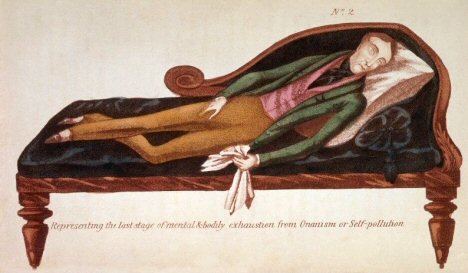

The guy fighting the nurses, in the photo on the right, is asleep. Although usually considered a restful state, sleep, for a minority of people with specific disorders, is a trigger for violence.

The guy fighting the nurses, in the photo on the right, is asleep. Although usually considered a restful state, sleep, for a minority of people with specific disorders, is a trigger for violence.

Anthropologist and explorer

Anthropologist and explorer  I’ve just found an amazing Terry Pratchett

I’ve just found an amazing Terry Pratchett  Science Oxford Online has an

Science Oxford Online has an

Slate has an amazing

Slate has an amazing

The New York Times has a revealing

The New York Times has a revealing  If, like me, you’re worried about the coming robot war, The New York Times has an

If, like me, you’re worried about the coming robot war, The New York Times has an  I recently indulged in the outrageous luxury of placing an international order for the

I recently indulged in the outrageous luxury of placing an international order for the  Legendary Polish neurologist

Legendary Polish neurologist  A wonderful poem simply titled ‘Thought’ by the English writer

A wonderful poem simply titled ‘Thought’ by the English writer