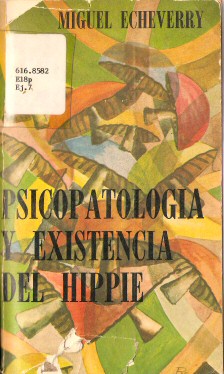

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion.

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion.

I found the book, called Psicopatologia y Existencia del Hippie (Psychopathology and Existence of the Hippy), in my local library and it turns out to be one of the most surprising psychiatry books I have ever read.

At some point, I suspect the good Dr Echeverry must have been driven to breaking point by a bunch of long-haired youths strumming poorly tuned guitars outside his window, because he is clearly furious.

This is his definition of a hippy, translated from p83, where he is so angry he forgets to use a full stop.

The true hippy is an individual with a frank disposition to hereditary psychopathology, who has abandoned himself, has totally neglected his hygiene and self-presentation, has let his hair and beard grow, is dressed bizarrely, eccentrically and ridiculously, wears a multitude of rings, necklaces, beads and other extravagances, is opposed to all defined and purposeful social and family structures now and in the future, rejects productive and redeeming work, irresponsibly and cynically promotes the cult of free love, aggressively promotes contempt for moral, social and religious conventions, preaches paradoxically about the abolition of private property, harmfully drugs them self with marijuana, LSD, amphetamines, hypnotics, mescaline, psylocybin, sedatives and heroin etc to rebelliously and insanely avoid the sad realities of life.

The author notes with disdain that the ‘hippy threat’ seems to be a particular problem in Bogotá, probably reflecting more than a little regional distrust of the free-wheeling capital.

The book contains not a single reference to any scientific or clinical study, although is happy to wax lyrical about the subgroups of the hippy mental illness. Apparently, there are five: hippies with defective personal relationships and autistic-like problems, aggressive hippies, hippies with defective behaviour and poor family adjustment, emotionally impaired hippies, and those with abnormal, perverted or inverted instincts.

For those worried that he may be getting a little too psychoanalytic, Dr Echeverry makes it clear that there is both a strong environmental and genetic component to hippy psychopathology. Yes, apparently, you can inherit hippidom.

The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

Considering the tone of the book, and the fact that the author concludes that being a hippy as akin to having schizophrenia, it’s interesting that Lucidril is not an antipsychotic, but the trade name for a little known compound called meclofenoxate.

There is weak evidence that the drug boosts memory and is notable largely for its enthusiastic uptake by some sections of the ‘nootropics’ brain hacking crowd.

I suspect the enthusiastic adverts for this oddball drug are largely because the book happened to be sponsored by pharmaceutical company Instituto Bio-Quimico Ltd who were clearly trying to sell the drug as a ‘mental detoxification’ compound for the great unwashed.

But not every bearded girl or guy is a real hippy, says Dr Echeverry, who notes that there are also cases of pseudo-hippies, who are really just weak-minded youths who get swept along with the genuine ‘clinical cases’.

How can you tell the difference you ask? Well, pseudo-hippies are the ones who revert to normality once a psychiatrist pumps them full of approved medication. Simple.

January’s British Journal of Psychiatry has another short article in its fantastic ‘100 words’ series, this time on Edvard Munch’s classic painting ‘The Scream‘.

January’s British Journal of Psychiatry has another short article in its fantastic ‘100 words’ series, this time on Edvard Munch’s classic painting ‘The Scream‘. Wired

Wired

The consistently sublime RadioLab has a wonderful

The consistently sublime RadioLab has a wonderful

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion.

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion. The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

Being in coma could play havoc with your nail care routine.

Being in coma could play havoc with your nail care routine.

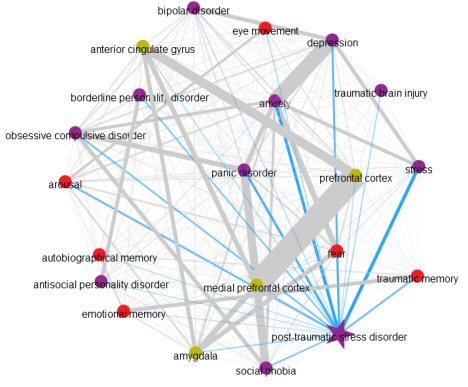

The brilliant Neuroskeptic has created a

The brilliant Neuroskeptic has created a