Nature has a fantastic article about how our sense of being located in our bodies is being temporarily warped and distorted in the lab of neuroscientist Henrik Ehrsson.

Nature has a fantastic article about how our sense of being located in our bodies is being temporarily warped and distorted in the lab of neuroscientist Henrik Ehrsson.

We’ve covered some of Ehrsson’s striking studies before as he has managed, with surprisingly simple equipment, to induce out-of-body experiences, the sense of having a third arm and the illusion of having a tiny doll-like body – among many other distortions.

But Ehrsson’s unorthodox apparatus amount to more than cheap trickery. They are part of his quest to understand how people come to experience a sense of self, located within their own bodies. The feeling of body ownership is so ingrained that few people ever think about it — and those scientists and philosophers who do have assumed that it was unassailable.

“Descartes said that if there’s something you can be certain of in this world, it’s that your hand is your hand,” says Ehrsson. Yet Ehrsson’s illusions have shown that such certainties, built on a lifetime of experience, can be disrupted with just ten seconds of visual and tactile deception. This surprising malleability suggests that the brain continuously constructs its feeling of body ownership using information from the senses — a finding that has earned Ehrsson publications in Science and other top journals, along with the attention of other neuroscientists.

The article looks at what this body distorting illusions are telling us about how the brain makes sense of our bodies and how these discoveries could be applied to ‘locating’ us in false limbs or even remote control robots.

Also don’t miss the podcast where author Ed Yong talks about his trip to the lab to try out the illusions.

Link to Nature article ‘Out-of-body experience: Master of illusion’.

I’ve just stumbled across a

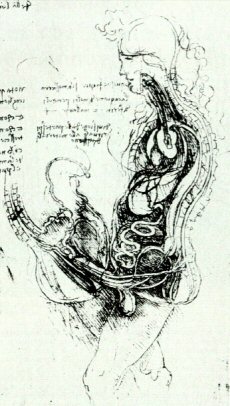

I’ve just stumbled across a  In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain.

In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain.

The New York Times has a fascinating

The New York Times has a fascinating  This is a

This is a

A new

A new  French sleep scientists have

French sleep scientists have  I’ve got a

I’ve got a