My latest Beyond Boundaries column for The Psychologist explores the space between he we study suicide and the experience of families affected by it:

My latest Beyond Boundaries column for The Psychologist explores the space between he we study suicide and the experience of families affected by it:

Suicide is often considered a silencing, but for many it is only the beginning of the conversation. A common approach to understand those who have ended their own lives is the ‘psychological autopsy’ – a method that seeks to reconstruct the mental state of the deceased individual shortly before the final act. The testimony of friends and family is filtered through standardised assessments and psychiatric diagnoses. The narrative is ‘stripped down’ to the essential facts. A life is reduced to risk factors.

Psychologists Christabel Owens and Helen Lambert were struck by the contrast between the goal of the professionals in the interviews and how the friends and family of the deceased used the opportunity to tell their story and to make sense of their loss. ‘The flow of narrative’, they note in their recent study, ‘can often be unstoppable’. The researchers returned to the transcripts of a 2003 psychological autopsy study, but instead of using the interview to construct variables, they looked at how the friends and families portrayed their lost companion.

As suicide is both stigmatised and stigmatising the personal accounts often contained portrayals of events that presupposed possible moral conclusions about the deceased. For example, by tradition, those who have cancer are discussed as heroic fighters, facing down death with courage and resolution. The default stories about people who commit suicide are not nearly so generous, however, and to navigate this treacherous moral territory bereaved friends and family often called on other, more acceptable, social stereotypes to make sense of the situation.

The suicides of women were largely portrayed in medical terms, as being so weakened by negative experiences that they were unable to prevent a decline into mental illness. The suicides of men, on the other hand, were barely ever described in terms of mental disorder. Male suicide was typically described either as the end result of having ‘gone of the rails’, a self-directed descent into antisocial behaviour, or as a ‘heroic’ action, demonstrating a final defiant act against an unjust world.

Deaths were filtered through gender stereotypes of agency and accountability, perhaps to make them more acceptable to an unkind world. Owens and Lambert’s study highlights the stark contrast between how researchers and family members interpret the same tragic events. As professionals, we often do surprisingly little to mesh together the bounded worlds of science and subjectivity, but the study demonstrates the power of the personal narrative. It affects us even after death.

Thanks to Jon Sutton, editor of The Psychologist who has kindly agreed for me to publish my column on Mind Hacks as long as I include the following text:

“The Psychologist is sent free to all members of the British Psychological Society (you can join here), or you can subscribe as a non-member by going here.

Link to original behind pay wall.

The latest

The latest

A fantastic

A fantastic  A

A

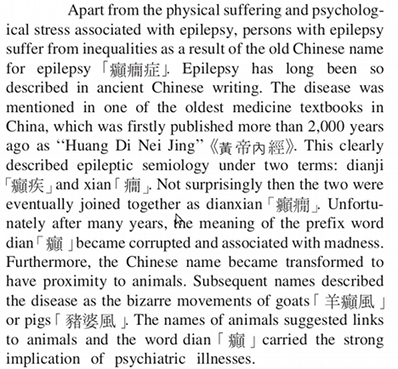

Of all the names for a neurological disorder in the history of medicine, the most awesome has got to be ‘Dark Warrior epilepsy’.

Of all the names for a neurological disorder in the history of medicine, the most awesome has got to be ‘Dark Warrior epilepsy’.

The Chinese character for

The Chinese character for  just makes reference to the brain although the story of how the original name got its meaning is quite fascinating in itself.

just makes reference to the brain although the story of how the original name got its meaning is quite fascinating in itself.

In 1992, the BBC broadcast

In 1992, the BBC broadcast