I’ve often seen people on the web who advertise themselves as ‘fashion psychologists’ who say they can ‘match clothes to your personality’. I’ve always rolled my eyes and moved on.

I’ve often seen people on the web who advertise themselves as ‘fashion psychologists’ who say they can ‘match clothes to your personality’. I’ve always rolled my eyes and moved on.

So I was fascinated to meet Carolyn Mair, a cognitive scientist who did her PhD in perceptual cognition, who now leads a psychology programme at the world-renowned London College of Fashion.

They are doing rigorous psychology as it applies to fashion, clothes and the beauty industry and I asked her to speak to Mind Hacks about herself and her work.

Can you say a little about your background?

My first job was as a ‘commercial artist’ (now graphic designer). Alongside this I made a reasonable income from painting portraits and murals. I then moved to Australia for two years where I worked in a cake shop/bakery where I was able to decorate cakes for special occasions. On returning to the UK, I became a mother and continued painting portraits and murals and also began to design and sell children’s clothes as well as cakes.

During this time, I studied on the BSc Applied Psychology and Computing at Bournemouth University in 1992 and then the MSc Research Methods Psychology at Portsmouth University in 1995. I was asked to do a PhD in Computational Neuroscience, a very young discipline in 1999, investigating the ‘binding problem’; specifically short-term visual memory. During this period I spent three months at the centre of Cognitive Neuroscience at SISSA in Trieste which dramatically changed the direction of my thesis from computational to cognitive neuroscience. I completed my postdoc in the Department for Information Science, Computing and Maths at Brunel University and then took up a Senior Lectureship at Southampton Solent University. I left there in 2012 to join London College of Fashion as Subject Director Psychology.

How did you get into the psychology of fashion?

I love fashion! I started making clothes for myself when I was 13 years old and for others during my teens and again when I had children. Following a chance meeting at a conference in 2011, I was asked to give a paper on psychology and fashion at London College of Fashion. I was then invited back to discuss how psychology could be introduced at Masters level. A role was created, I applied and was successful. I have since developed the world’s first Masters programmes, an MA and MSc, to apply psychology to or, in the context of, fashion.

Why does fashion need psychology?

Fashion is about perception, attention, memory, creativity and communication; it involves reasoning, decision-making, problem-solving and social interaction. Fashion is psychology! Although it has been interpreted anecdotally in psychological terms for centuries, applying psychology to fashion as a scientific endeavour is very new.

Psychology matters beyond what our clothes say about us. People are involved in every aspect of fashion from design, though production, manufacture, advertising and marketing, visual merchandising, retail, consumption and disposal. Taking a scientific approach enables us to derive a more meaningful understanding of behaviour related to fashion and therefore to predict and ultimately change behaviour for the better. We know that within one second of seeing another person, we decide how attractive they are, whether we like them and what sort of characteristics they possess. In addition, what we wear can affect our mood and confidence, and interestingly, what we believe about what we are wearing influences our cognitive performance.

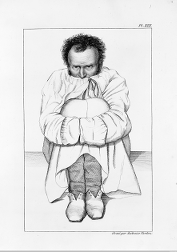

However, the ultimate impact and value of applying psychology to fashion goes beyond what we wear. The fashion industry is an important global industry which employs millions of people worldwide and ultimately involves us all. Since the 60s, the fashion industry has promoted a very narrow stereotype of ‘beauty’ which has now become the ‘norm’ through the ubiquity of web and mobile technology. With the increase in exposure to such images, comes an increase in body dissatisfaction across the lifespan. This brings multiple behavioural issues which can be addressed by psychologists.

In addition, psychologists can challenge the status quo and promote a more inclusive and diverse representation of what is ‘beautiful’ by demonstrating the benefits such an approach would bring. The narrow stereotype of beauty is reinforced through the multibillion pound cosmetic industry. The repercussions of this can be seen in the increase in demand for cosmetic surgery and other interventions many of which are conducted by unqualified practitioners on vulnerable individuals. The impact of such practice is yet to be fully realised, but psychologists are concerned at the lack of regulations that currently exist.

The fashion industry has a poor reputation in terms of the environment and sustainability. In fact, sustainable fashion can be considered an oxymoron. However, it is possible to have a sustainable fashion industry which considers the environment and consumers who care more about what they buy and in doing so buy less. Working alongside fashion professionals, the role of psychology in addressing these issues is education.

When I started applying psychology to fashion, I was determined not be a ‘wardrobe therapist’ or a ‘fashion psychologist’. I am often asked to write about what a particular garment or accessory says about the wearer, for example do glasses suggest intelligence or what does a politician’s fashion style say about him or her? My typical response is that deriving deep meaning from a single ‘snapshot’ is unrealistic as it’s more complex than that! I have been surprised about the demand for this sort of information and think the time is right for developing this new sub-discipline of psychology that has the potential to do good at individual, societal and community levels.

Fashion is a multibillion global industry which employs millions of people worldwide. As a result it affects, and is affected by the intricacies, fallibilities and fragility of human behaviour. In addition to those impacted by fashion as employer; fashion influences its consumers at all levels. Even if we consider ourselves not interested in fashion per se, we all wear clothes! Until recently, the scientific study of psychology applied in the context of fashion has been neglected. This important area, which affects billions worldwide, is in obvious need of investigation.

Name three under-rated things

Looking healthy as opposed to looking young

Getting older

Chilling out

Somewhat unexpectedly, Vice magazine has just launched a

Somewhat unexpectedly, Vice magazine has just launched a

I’ve just read

I’ve just read  Last year I did a talk in London on auditory hallucinations, The Beach Boys and the psychology and neuroscience of hallucinated voices, and I’ve just discovered the

Last year I did a talk in London on auditory hallucinations, The Beach Boys and the psychology and neuroscience of hallucinated voices, and I’ve just discovered the  The New York Review of Books has an excellent new

The New York Review of Books has an excellent new  The U-T San Diego, which I originally thought was a university but turns out it’s a newspaper, has an excellent online multimedia

The U-T San Diego, which I originally thought was a university but turns out it’s a newspaper, has an excellent online multimedia  The Psychologist has a fascinating

The Psychologist has a fascinating