The New York Times covers an important and provocative speech made at a recent big name social psychology conference where the keynote speaker Jonathan Haidt questioned whether social psychologists are blind ‘to the hostile climate they’ve created for non-liberals’.

The New York Times covers an important and provocative speech made at a recent big name social psychology conference where the keynote speaker Jonathan Haidt questioned whether social psychologists are blind ‘to the hostile climate they’ve created for non-liberals’.

It’s a brave move and he brings up some important points about the narrow perspective the field has cultivated and its impact on our ways of understanding the world.

“Anywhere in the world that social psychologists see women or minorities underrepresented by a factor of two or three, our minds jump to discrimination as the explanation,” said Dr. Haidt, who called himself a longtime liberal turned centrist. “But when we find out that conservatives are underrepresented among us by a factor of more than 100, suddenly everyone finds it quite easy to generate alternate explanations.”…

Dr. Haidt (pronounced height) told the audience that he had been corresponding with a couple of non-liberal graduate students in social psychology whose experiences reminded him of closeted gay students in the 1980s. He quoted — anonymously — from their e-mails describing how they hid their feelings when colleagues made political small talk and jokes predicated on the assumption that everyone was a liberal.

Haidt highlights an interesting taboo about criticising the victims of discrimination, where even voicing these ideas – regardless of their accuracy – are enough to have someone cast out from the ‘tribal moral community’.

Even if you don’t agree with all his points, the lack of political diversity in social psychology is an important issue that has been glossed (glazed?) over for too long.

Link to NYT piece ‘Social Scientist Sees Bias Within’ (via @jonmsutton)

While in Barcelona I discovered a fantastic psychiatry-themed sweet shop called Happy Pills which sells every possible candy you could imagine packaged into mood-lifting pill bottles.

While in Barcelona I discovered a fantastic psychiatry-themed sweet shop called Happy Pills which sells every possible candy you could imagine packaged into mood-lifting pill bottles.

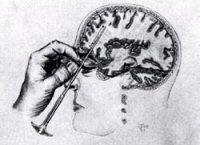

New stimulant street drug

New stimulant street drug

Dana has an eye-opening

Dana has an eye-opening

The Royal Society has just released a fantastic

The Royal Society has just released a fantastic

New York Magazine has an in-depth

New York Magazine has an in-depth