This is a video of people dancing with a recently deceased baby and it tells us something profound about the psychology of grief and mourning.

This is a video of people dancing with a recently deceased baby and it tells us something profound about the psychology of grief and mourning.

Despite a common stereotype, death of a loved one can provoke some of the most culturally diverse forms of emotion and social ritual.

The video is rare footage of the Chigualo ceremony, a mourning ritual for children aged less than seven-years-old who have just passed away from the Afrocolombian community of the Pacific coast of Colombia.

Unfortunately, there is almost nothing written about the ceremony available online in English but the Spanish language Wikipedia has good page about it.

The belief behind the ceremony is that when young children die they become angels and go straight to heaven. Therefore, these deaths are not an occasion for sadness, as many might assume, but a cause for a goodbye celebration.

You can see in the video that the Chigualo involves upbeat rhythms, singing, games and dancing – including passing the dead baby between people at the ceremony.

This may seem shocking or disrespectful to people accustomed to sadness and distress-based mourning, but in its own community it is the single most respectful way of saying goodbye to a recently blessed angel.

Psychology has a stereotype problem with grief and mourning. Over and over again false assumptions are repeated, not even valid in Western cultures, that there are certain ‘stages’ to grief, that people will reliably react in certain ways with certain key emotions – sadness, anger, resignation and so on.

This leads to both a professional pathologising of grieving people including endless variations on ‘the person hasn’t accepted their loss’, ‘they haven’t elaborated their grief’ and ‘they’re in denial’ applied to anyone who doesn’t mourn within the expected boundaries.

Moreover, it leads to a cultural blindness about how other societies feel and understand the loss of others with the implicit assumption that the experience of grief is somehow universal.

Any other reaction except extended sadness is considered to be a way of ‘masking’ supposedly inevitable pain. ‘Underneath’, it is assumed, everyone must feel the same as ‘us’.

This is despite the fact that we have a huge array of anthropological work on the vast variation in grief and mourning throughout the world.

The Akan have elaborate rituals that punctuate the year to keep the memory of dead alive. The Achuar prohibit any attempts to remember or memoralise the deceased.

The Ganda prohibit sexual activity during mourning, the Cubeo have sexual activity as part of the mourning ceremony.

A Dogon funeral is designed to ensure that spirits of the dead leave the community, an Igbo funeral that they stay.

Although death is perhaps the only experience guaranteed to be universal, our reaction to it is one of the most diverse. Consequently, respect comes in many forms.

Link to video of Chigualo ceremony.

I’ve just found a sublime

I’ve just found a sublime

Nature has a fantastic

Nature has a fantastic

I’ve just stumbled across a

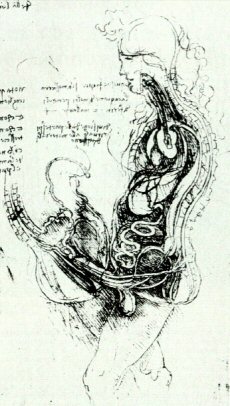

I’ve just stumbled across a  In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain.

In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain.

The New York Times has a fascinating

The New York Times has a fascinating  This is a

This is a