Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Neuroscience hip-hop. The Beautiful Brain discovers a new track from Prince Ea where he waxes lyrical about the cortex. The neurobiological microphonist discusses the track here.

The New York Times says to forget what you know about good study habits and discusses where the cognitive science of learning conflicts with teacherly advice.

The future of reading and how tweaking fonts could cause us to process text differently are discussed over at The Frontal Cortex. See also a piece riffing on the recent study on mobile phone half-a-logues.

BBC News has an in-depth article on cutting drugs and how the supply of adulterants to illicit dealers has become a big business in its own right.

Problem drug users are possibly the most stigmatised group of patients. Addiction Inbox looks at how drug policy needs to change to take these social obstacles into account.

Slate has an excellent analysis of ‘HauserGate‘ and why the drive for evidence can be a Siren’s call.

The first medical cannabis advert airs in the US, advertising cannabis for, er, just about any illness you can think of. Dosenation has the video.

NPR has a short radio piece on the top five things parents worry about and the genuine top five dangers to children. There is no overlap.

There’s a fantastic piece on the subtle reaping by carbon monoxide poisoning over at Speakeasy Science.

Wired Danger Room reports on the record number of US troops taking psychiatric medication.

If you read only one piece on oxytocin this week make it this great piece from Wonderland that looks at the differing effects of the hormone and male and female parents and skips the ‘hug drug’ stereotype.

The Guardian has a fantastic piece on the remarkably problem solving abilities of slime moulds. The B-movie version is in the works.

The excellent Providentia blog has a great piece on Thomas de Quincey “one of the high priests of the literary drug culture” – famous for his book ‘Confessions of an English Opium Eater’.

The Psychologist is looking for new voices and brand new talent for its pages. If you’ve not published much, or anything before, but have a passion for writing, this could be your chance.

The woman whose new memories are erased each night. The BPS Research Digest covers an intriguing and unusual form of amnesia.

BBC News has some fantastic coverage of the biomechanical analysis of attractive male dancing styles study. Although, according to the conclusions of the research, the funky chicken should be sexual dynamite.

A new meta-analysis debunks the link between psychopathy and violence and In the News has the low-down.

New Scientist has a lamentable article were they ask the head of the UK’s first and only private internet addiction clinic whether ‘internet addiction’ really exists. Next week, head of Eli Lilly asked which is the best pill to treat depression.

How the mind counteracts offensive ideas. Great review of how we mentally push back against things we don’t like.

All in the Mind from ABC Radio National discusses climate change and the psychology of mass behaviour change for the collective good.

There’s an interesting project developing at the History of Madness blog where they’re publishing the syllabus from a number of university courses on the history of psychiatry from around the world.

The New York Times has an in-depth article that asks can preschoolers be depressed?

A fascinating look at supposedly new slang like ‘gonna’ and ‘shoulda’ over at LanguageLog digs up the fact that they have a fine vintage in the English language.

Nature News has a feature article on the science of nurture and epigenetics.

Maximum amount of alcohol consumed in 24 hours by parents predicts mental health problems in teenagers. Another fascinating look at recent research by Evidence Based Mummy.

The New York Times Opinionator blog has a piece introducing the concept of ‘experimental philosophy’.

The latest edition of the American Psychological Association’s Monitor magazine is online and open.

Newsweek discusses the many facets of alcoholism and why abstinence isn’t always the only solution.

The environmental influence on the heredity of intelligence is discussed over at Spiegel which is one of the few mainstream articles that seems to get the idea that genetic influence isn’t fixed.

The Washington Post discusses the popularity of hallucinogenic ayahuasca ceremonies for Peruvian tourists.

Britney Spears’ tongue. As LanguageLog notes “It’s not very often that an observation about articulatory phonetics goes viral.” Exactly what I was thinking.

Writer Douglas Coupland has a playful article in the The Independent where he defines ‘new terms for new sensations’ and lists new psychological states that may be arising from 21st century life.

Writer Douglas Coupland has a playful article in the The Independent where he defines ‘new terms for new sensations’ and lists new psychological states that may be arising from 21st century life.

The Atlantic has an amazing

The Atlantic has an amazing

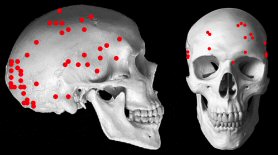

Gunshot wounds to the head are a major cause of death among soldiers in combat but little is known about where bullets are more likely to impact. A

Gunshot wounds to the head are a major cause of death among soldiers in combat but little is known about where bullets are more likely to impact. A

The Twilight series of young adult novels “could be affecting the dynamic workings of the teenage brain in ways scientists don’t yet understand” according to a bizarre

The Twilight series of young adult novels “could be affecting the dynamic workings of the teenage brain in ways scientists don’t yet understand” according to a bizarre

Oscillatory Thoughts has a brilliant

Oscillatory Thoughts has a brilliant