Seed Magazine has an excellent piece on ‘redefining mental illness’ that discusses the limits of labelling mental disorders and whether we can understand disability purely in terms of the mind.

Seed Magazine has an excellent piece on ‘redefining mental illness’ that discusses the limits of labelling mental disorders and whether we can understand disability purely in terms of the mind.

The piece captures the highlights from a recent online blog discussion on the topic and is inspired in part by the ongoing update to the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual, the DSM-5, due to be released in May 2013.

One of the big changes to the manual is likely to be the introduction of dimensions, so instead of just having to decide whether “you have it or you don’t” psychiatrists will be able to rate symptoms on a sliding scale.

This has been inspired evidence that hallucination-like experiences or unlikely magical beliefs are not restricted to people with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, but are also present, albeit to varying degrees, in everyone.

This has led some to argue that we should abandon diagnoses for mental disorders as they’re just arbitrary cut-off points that have no scientific basis.

But if everyone has their own ‘unique dose’ of unusual experiences, like everyone has their ‘unique dose’ of typical daily anxiety, we should see a nice smooth curve when we measure it in the population. Some people have a little, some people have lots, and we should find everyone else in between.

It turns out, that this is not the case with hallucinations, delusions, reality distortions and unusual magical beliefs.

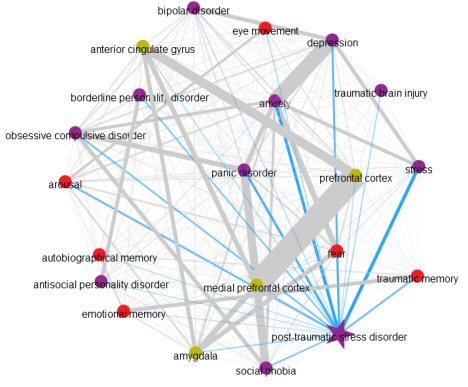

A recent over-arching meta-analysis of all the data from past research suggests that some people show a qualitative difference in the type of psychosis-like experiences they have – in other words, there is a natural break – but this doesn’t match up with who is likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Here are the authors in their own words:

The weight of evidence suggests there is a nonarbitrary boundary between those with and without schizophrenia. Certainly, the prevalence estimates of the psychometric risk categories indicate that this nonarbitrary boundary is well below the threshold for schizophrenia, capturing approximately 11% of the population.

In other words, there is not a smooth continuum between normality and schizophrenia. In fact, there seems to be clear difference in 11% of the population, but this happens in most cases in people who never become mentally ill.

Less than 1% of the population will qualify for a diagnosis of schizophrenia and only 3% for any type of psychotic disorder involving hallucinations and delusions.

That leaves 8% who have, perhaps what we could call ‘schizophrenia-like’ unusual experiences (as opposed to ‘regular’ unusual experiences), but who don’t ever seem to become disabled.

What this may mean is that defining mental disorders like schizophrenia largely on the basis of certain experiences may be missing the point, because they don’t in themselves cause a problem for most people.

But what this also means, is that the diagnostic manuals will remain very rough guesses until the publishers decided to draw their diagnoses from science, rather than doing science to try and justify their diagnoses.

Link to Seed on ‘Redefining Mental Illness’.

Link to ‘What is Mental Illness’ blog carnival.

Link to PubMed entry for meta-analysis of psychosis-like experiences.

The New York Times has a fantastic interview with Emery Neal Brown, a neuroscientist and doctor who is trying to understand how anaesthesia works to better understand the brain and to build better drugs.

The New York Times has a fantastic interview with Emery Neal Brown, a neuroscientist and doctor who is trying to understand how anaesthesia works to better understand the brain and to build better drugs. In the debate about the ability of language to adequately describe conscious experience, jazzed-out rappers

In the debate about the ability of language to adequately describe conscious experience, jazzed-out rappers  Australian science reporter Professor Funk has made a fantastic animated

Australian science reporter Professor Funk has made a fantastic animated

A remarkably accurate account of the

A remarkably accurate account of the  The New York Times

The New York Times

New stimulant street drug

New stimulant street drug  Dana has an eye-opening

Dana has an eye-opening  Wired

Wired

Cannibalism is a lot more common in human history than you’d guess and an intriguing

Cannibalism is a lot more common in human history than you’d guess and an intriguing