The Headlines

The Independent: First ever human brain-to-brain interface successfully tested

BBC News: Are we close to making human ‘mind control’ a reality?

Visual News: Mind Control is Now a Reality: UW Researcher Controls Friend Via an Internet Connection

The story

Using the internet, one researcher remotely controls the finger of another, using it to play a simple video game.

What they actually did

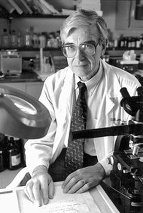

University of Washington researcher Rajesh Rao watches a very simple video game, which involved firing a cannon at incoming rockets (and avoiding firing at incoming supply planes). Electrical signals from his scalp were recorded using a technology called EEG and processed by a computer. The resulting signal was sent over the internet, and across campus, to a lab where another researcher, Andrea Stocco, watches the same video game with his finger over the “fire” button.

Unlike Rao, Stocco wears a magnetic coil over his head. This is designed to invoke electrical activity, not record it. When Rao imagines pressing the fire button, the coil activates the area of Stocco’s brain that makes his finger twitch, thus firing the cannon and completing a startling demonstration of “brain to brain” mind control over the internet.

You can read more details in the University of Washington press release or on the “brain2brain” website where this work is published.

How plausible is this?

EEG recording is a very well established technology, and takes advantage of the fact that the cells of our brain operate by passing around electrochemical signals which can be read from the surface of the scalp with simple electrodes. Unfortunately, the intricate details of brain activity tend to get muffled by the scalp, and the fact that you are recording at one specific point in space, so the technology’s strength is more in telling us that brain activity has changed, rather than in saying how or exactly where brain activity has changed.

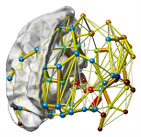

The magnetic coil which made the receiver’s finger twitch is also well established, and known in the business as Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS). An alternating magnetic field is used to alter brain activity underneath the coil. I’ve written about it here before.

The effect is relatively crude. You can’t make someone play the violin, for example, but activating the motor cortex in the right region can generate a finger twitch. So, in summary, the story is very plausible. The researchers are well respected in this area and open about the limitations of their research. Although the experiment wasn’t published in a peer-reviewed journal, we have every reason to believe what we’re being told here.

Tom’s take

This is a wonderful piece of “proof of concept” research, which is completely plausible given existing technology, but yet hints at the possibilities which might soon become available.

The real magic is in the signal processing done. The dizzying complexities of brain activity are compressed into an EEG signal which is still highly complex, and pretty opaque as to what it means – hardly mind reading.

The research team then managed to find a reliable change in the EEG signal which reflected when Rao was thinking about pressing the fire button. The signal – just a simple “go”, as far as I can tell – was then sent over the internet. This “go” signal then triggered the TMS, which is either on or off.

In information terms, this is close to as simple as it gets. Even producing a signal which said what to fire at, as well as when to fire, would be a step change in complexity and wasn’t attempted by the group. TMS is a pretty crude device. Even if the signal the device received was more complex, it wouldn’t be able to make you perform complex, fluid movements, such as those required to track a moving object, tie your shoelaces or pluck a guitar. But this is a real example of brain to brain communication.

As the field develops the thing to watch is not whether this kind of communication can be done (we would have predicted it could be), but exactly how much information is contained in the communication.

A similar moral holds for reports that researchers can read thoughts from brain scans. This is true, but misleading. Many people imagine that such thought-reading gives researchers a read out in full technicolour mentalese, something like “I would like peas for dinner”. The reality is that such experiments allow the researchers to take a guess at what you are thinking based on them having already specified a very limited set of things which you can think about (for example peas or chips, and no other options).

Real progress on this front will come as we identify with more and more precision the brain areas that underlie complex behaviours. Armed with this knowledge, brain interface researchers will be able to use simple signals to generate complex responses by targeting specific circuits.

Read more

The original research report: Direct Brain-to-Brain Communication in Humans: A Pilot Study

Previously at The Conversation, another column on TMS: Does brain stimulation make you better at maths?

Thinking about brain interfaces is helped by a bit of information theory. To read a bit more about that field I recommend James Gleik’s book The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Nature Medicine has a fascinating

Nature Medicine has a fascinating

The New York Times has an

The New York Times has an

The New York Times has an

The New York Times has an

I often get asked ‘how can I avoid common misunderstandings in neuroscience’ which I always think is a bit of an odd question because the answer is ‘learn a lot about neuroscience’.

I often get asked ‘how can I avoid common misunderstandings in neuroscience’ which I always think is a bit of an odd question because the answer is ‘learn a lot about neuroscience’.

Nature has an

Nature has an