A guy who enjoyed whacking off while trying to strangle himself has provided important evidence that an outward sign considered to indicate severe irreversible brain damage can be present without any lasting effects.

It was long thought that a body response called decerebrate rigidity – where the body becomes stiff with the toes pointing and the wrists bending forward – was a sign of irreversible damage to the midbrain.

This sign is widely used in medical assessments to infer severe brain damage and has been observed in videos of people being executed by hanging.

A new study in The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology provides striking evidence that it is possible to recover from decerebrate rigidity owing to self-taped videos of a man who would strangle himself with a pair of pyjama pants suspended from the shower while masturbating.

The practice is known as autoerotic asphyxia and is based on the idea that restricted oxygen can enhance sexual pleasure – although is not recommended, not least because the medical literature is awash with cases of people who have died while attempting it.

Indeed, the gentleman described in the study did eventually die while hanging himself and when the forensic team investigated his house they found videos where he had filmed himself undertaking the risky sexual practice.

The three videos show him hanging himself while masturbating to the point where he lost consciousness and had the equivalent of an epileptic tonic-clonic seizure as he crashed to the ground. Each time, he regains consciousness and has no noticeable lasting effects.

In one of the videos, 20 seconds of decerebrate rigidity are clearly present. This was previously thought to be a sign of severe permanent brain damage – and yet he comes round, picks himself up and seems unaffected.

The study makes the interesting point that we still know very little about the effects of oxygen starvation on the brain.

For example, the widely quoted figure about brain cells dying after three to five minutes without oxygen is based entirely on animal studies and we don’t actually know the limit for humans.

As the authors note “There is no study to document this threshold of 3 to 5 minutes of ischemia [oxygen deprivation] to cause irreversible brain damage in human beings. Nevertheless, data obtained from animal studies were applied to human beings and the source of the threshold was later forgotten and assumed to be reliable.”

Link to PubMed entry for study.

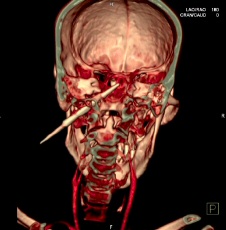

The image is a 3D CT scan of someone who was shot in the head with an arrow which penetrated their brainstem.

The image is a 3D CT scan of someone who was shot in the head with an arrow which penetrated their brainstem. I’ve just finished Carl Zimmer’s new

I’ve just finished Carl Zimmer’s new  I have to admit, I’m a little bored with consciousness, and my heart slightly sinks when I see yet another piece that rehashes the same old arguments. However, I thoroughly enjoyed this refreshing Cristof Koch

I have to admit, I’m a little bored with consciousness, and my heart slightly sinks when I see yet another piece that rehashes the same old arguments. However, I thoroughly enjoyed this refreshing Cristof Koch

The Washington Post has an amazing series of

The Washington Post has an amazing series of

Ohio State University have created a fantastic interactive web

Ohio State University have created a fantastic interactive web  Electronic devices that interface directly with the brain are now being produced by labs around the world but each new device tends to work in a completely different way. An

Electronic devices that interface directly with the brain are now being produced by labs around the world but each new device tends to work in a completely different way. An  The New York Times has an excellent

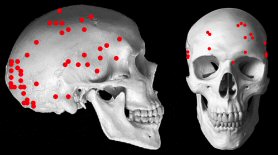

The New York Times has an excellent  Gunshot wounds to the head are a major cause of death among soldiers in combat but little is known about where bullets are more likely to impact. A

Gunshot wounds to the head are a major cause of death among soldiers in combat but little is known about where bullets are more likely to impact. A

The New York Times

The New York Times