Both of this year’s lead Oscar winners have published scientific papers on neuroscience. We’ve covered Natalie Portman’s work on frontal lobe development in children before, but it turns out Colin Firth has also just co-authored a study on structural brain differences in people with differing political views.

Both of this year’s lead Oscar winners have published scientific papers on neuroscience. We’ve covered Natalie Portman’s work on frontal lobe development in children before, but it turns out Colin Firth has also just co-authored a study on structural brain differences in people with differing political views.

An excellent post on The Neurocritic tells the intriguing story of how the study came about.

It turns out Firth was a guest editor on the daily BBC Radio 4 news programme Today and commissioned neuroscientist Geraint Rees to scan the brains of two prominent UK politicians – one staunchly liberal and the other a confirmed conservative – to look for differences.

The piece was clearly a piece of news fluff – as you can tell very little from scanning just two people – but it was motivated by a genuine interest in whether political opinions correlate with brain differences.

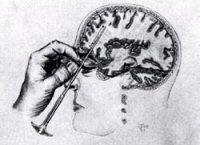

Rees decided to develop the idea into a more comprehensive study, using scans from 90 people, to see whether the density of the brain’s grey matter differed in line with differences in political views.

The study didn’t look at differences across the whole brain, just the anterior cingulate, a part of the frontal lobes, and the deep brain structure the amygdala.

The areas were chosen because previous studies have found that conservatives are more sensitive to fear-inducing prompts – a response linked to the amygdala, whereas liberals show more brain activity in the anterior cingulate when they have to hold back an automatic response.

It must be said that the link between these functions and brain areas is still quite preliminary, so the study is more of an exploration than a cast-iron test of a well-defined idea.

This new study, published in Current Biology and co-authored by Colin Firth, Geraint Rees along with neuroscientist Ryota Kanai and the producer of the Radio 4 programme, found distinct differences in these areas.

We found that greater liberalism was associated with increased gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate cortex, whereas greater conservatism was associated with increased volume of the right amygdala

This doesn’t tell us anything about whether conservatives or liberals are “born or made”. Despite the fact that the whole question is daft and over-simplified, a simple association between beliefs and brain areas doesn’t help us understand anything about cause and effect.

It could be that the brain areas differ because conservatives and liberals differ in how much they ‘practice’ alternative ways of thinking about the world, rather than brain structure ‘determining’ political orientation.

I really recommend the Neurocritic piece for more background, but the fact that the 2011 winners of the best actor and actress Oscar both have their name on neuroscience studies shows how fashionable the science has become.

And if, by chance, a certain Grammy award winning She Wolf would like to join the trend I would be more than willing to help out with the statistical analysis.

Yes, I realise my chat-up lines could do with a bit of work.

Link to The Neurocritic on Colin Firth’s neuroscience study.

The neuroscience of suggestion and hypnosis are helping us to understand mysterious disorders where people are blind or paralysed with no apparent medical explanation, and may be useful in investigating altered states from diverse cultures – according to an engaging discussion in the monthly JNNP

The neuroscience of suggestion and hypnosis are helping us to understand mysterious disorders where people are blind or paralysed with no apparent medical explanation, and may be useful in investigating altered states from diverse cultures – according to an engaging discussion in the monthly JNNP  Those autotune-friendly science remix chaps Symphony of Science have just released a new

Those autotune-friendly science remix chaps Symphony of Science have just released a new

The New York Times has a fantastic

The New York Times has a fantastic  BBC Radio 4’s Case Notes has an excellent

BBC Radio 4’s Case Notes has an excellent  BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time has a wonderful programme on the history of our knowledge about the nervous system which you can listen to streamed from the

BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time has a wonderful programme on the history of our knowledge about the nervous system which you can listen to streamed from the  The addiction journal Substance Abuse has two

The addiction journal Substance Abuse has two

The Royal Society has just released a fantastic

The Royal Society has just released a fantastic

Ecstasy users often describe the high as feeling ‘loved up’ and

Ecstasy users often describe the high as feeling ‘loved up’ and