The Chronicle of Higher Education has an excellent in-depth article on the most likely candidate for a revolution in mental health research: the National Institute of Mental Health’s RDoC or Research Domain Criteria project.

The Chronicle of Higher Education has an excellent in-depth article on the most likely candidate for a revolution in mental health research: the National Institute of Mental Health’s RDoC or Research Domain Criteria project.

The article is probably the best description of the project this side of the scientific literature and considering that the RDoC is likely to fundamentally change how mental illness is understood, and eventually, treated, it is essential reading.

It is also interesting for the fact that the leaders of the RDoC project continue to hammer the reputation of the long-standing psychiatric diagnosis manual – the DSM.

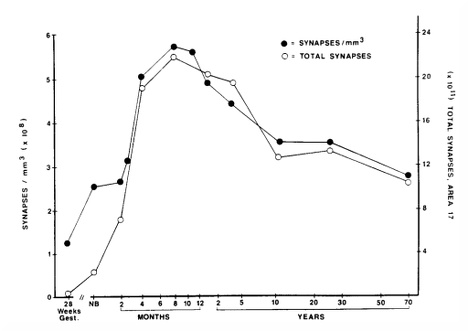

First though, it’s worth knowing a little about what the RDoC actually is. Essentially, it’s a catalogue of well-defined neural circuits that are associated with specific cognitive functions or emotional responses.

If you look at the RDoC matrix you can see how everything has been divided. For example, stress regulation is associated with the raphe nuclei circuits and serotonin system.

The idea is that mental illnesses would be better understood as dysfunctions in various of these core components of behaviour rather than the traditional collections of symptoms that have been rather haphazardly formed into diagnoses.

Conceptually, it’s like a sort of neuropsychological Lego that should allow researchers to focus on agreed components of the brain and see how they map on to genes, behaviour, experience and so on.

It’s meant to be updated over time so ‘bricks’ can be modified or added as they become confirmed. An advantage is that is may allow a more accessible structure to understanding the brain for those not trained in neuroscience but there is a danger that it will over-simplify the components of experience and behaviour in some people’s minds (and, of course, research).

The RDoC has been around for several years but it recently hit the headlines when NIMH director Thomas Insel wrote a blog post promoting it two weeks before the launch of the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual, the DSM-5, saying that the DSM ‘lacks validity’ and that “patients with mental disorders deserve better”.

After a media storm, Insel wrote another piece jointly with the president of the American Psychiatric Association that involved some furious backpeddling where the DSM was described as a “key resource for delivering the best available care” and “complementary” to the RDoC approach.

But in the Chronicle article, head of the RDoC project, Bruce Cuthbert, makes no bones about the DSM’s faults:

“If you think about it the way I think about it, actually the DSM is sloppy in both counts. There’s no particular biological test in it, but the psychology is also very weak psychology. It’s folk psychology without any quantification involved.”

The DSM will not, of course, suddenly disappear. “As flawed as the DSM is, we have no substitute for the clinical realm for insurance reimbursement,” ex-NIMH Director Steven Hyman says in the article.

It’s worth noting that this is not actually true. In the US, diagnosis is usually made according to DSM definitions but insurance reimbursement is charged by codes from the ICD-10 – the free diagnostic manual from the World Health Organisation.

But the fact that the most senior psychiatric researchers in the US are now openly and persistently highlighting that the DSM is not fit for the purpose of advancing science and psychiatric treatment is a damning condemnation of the manual – no matter how they try and sugar-coat it.

The fact is, the NIMH have to walk a fine line. They need to both condemn the DSM for being a mess while trying not to shatter confidence in a system used to treat millions of patients every year.

Best of luck with that.

Link to Chronicle article ‘A Revolution in Mental Health’.

Nature Medicine has a fascinating

Nature Medicine has a fascinating

Roger Ebert’s 2006

Roger Ebert’s 2006

An article in the Guardian Headquarters blog

An article in the Guardian Headquarters blog

The New York Times has an

The New York Times has an

I’ve just finished reading the new

I’ve just finished reading the new