Two years ago we discussed a puzzling, sometimes fatal, ‘nodding syndrome‘ that has been affecting children in Uganda and South Sudan. We now know a little more, with epilepsy being confirmed as part of the disorder, although the cause still remains a mystery.

Two years ago we discussed a puzzling, sometimes fatal, ‘nodding syndrome‘ that has been affecting children in Uganda and South Sudan. We now know a little more, with epilepsy being confirmed as part of the disorder, although the cause still remains a mystery.

The condition affects children between 5 and 15 years old, who have episodes where they begin nodding or lolling their heads, often in response to cold. A typical but not exclusive pattern is that over time they become cognitively impaired to the point of needing help with simple tasks like feeding. Stunted growth is common.

Global Health News have a video on the condition if you want to see how it affects people.

In terms of our medical understanding, a review article just published in Emerging Infectious Diseases collates what we now know about the condition.

Firstly, it is now clear that epilepsy is part of the picture and the nodding is caused by recurrent seizures in the brain. This is a bit curious because this type of very specific ‘nodding’ behaviour has not been seen as a common effect of epilepsy before.

Also, knowing that it is caused by a seizure just pushes the need for explanation further down the causal chain. Seizures can occur through many different forms of brain disruption, so the question becomes – what is causing this epidemic form of seizure that seems to have a very selective effect?

With this in mind, a lot of the most obvious candidates have been ruled out. The following is from the review article, but if you’re not up on your medical terms, essentially, tests for a lot of poisons or infections have come up negative:

Testing has failed to demonstrate associations with trypanosomiasis, cysticercosis, loiasis, lymphatic filariasis, cerebral malaria, measles, prion disease, or novel pathogens; or deficiencies of folate, cobalamin, pyridoxine, retinol, or zinc; or toxicity from mercury, copper, or homocysteine.

Brain scans have been inconclusive with some showing minor abnormalities while others seem to show no detectable damage.

There have been some curious but not conclusive associations, however. Children with the nodding syndrome are more likely to have signs of infection by the river blindness parasite. But huge swathes of Africa have endemic river blindness and no nodding syndrome, and some children with nodding syndrome have no signs of infection.

Furthermore, the parasite is not thought to invade the nervous system and no trace of it has been found in the cerebrospinal fluid from any of the people with the syndrome. The authors of the review speculate that a new or similar parasite could be involved but hard data is still lacking and the typical signs of infection are missing.

A form of vitamin B6 deficiency is known to cause neural problems and has been found in affected people but it has also been found in just as many people untouched by the mystery illness. One possibility is this could be a risk factor, making people more vulnerable to the condition, rather than a sole cause.

One idea as to why it is so specific relates to the increasing recognition that some neurological conditions are caused by the body’s immune system erroneously attacking very specific parts of the brain.

For example, in Sydenham’s chorea antibodies for the common sore throat bacteria end up attacking the basal ganglia, while in limbic encephalitis the immune system attacks the limbic system.

This sort of autoimmune problem is a reasonable suggestion given the symptoms, but in the end, it is another hypothesis that is awaiting hard data.

Perhaps most mysterious, however, is its most marked feature – the fact that it only seems to affect children. At the current time, we seem no closer to understanding why. Similarly, the fact that it is epidemic and seems to spread also remains unexplained.

If you’re used to scientific articles, do check out the Emerging Infectious Diseases paper because it reads like a as-yet-unsolved detective story.

Either way, keep tabs on the story as it is something that needs to be cracked, not least because the number of cases seems to be slowly increasing.

Link to update paper in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

New York Magazine has an excellent piece on whether adolescence is really a time of turmoil for young people or whether it is actually the parents that find their kids’ teenage years the most challenging.

New York Magazine has an excellent piece on whether adolescence is really a time of turmoil for young people or whether it is actually the parents that find their kids’ teenage years the most challenging.

The Psychologist has a fascinating

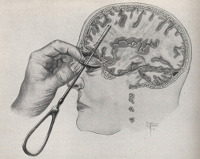

The Psychologist has a fascinating  The image on the left is from a 1952

The image on the left is from a 1952  The drawing on the right was completed by a patient in a medical

The drawing on the right was completed by a patient in a medical  In the drawing on the left, a patient who suffered spinal damage that caused a loss of sensation in their limbs, illustrated how their phantom legs felt.

In the drawing on the left, a patient who suffered spinal damage that caused a loss of sensation in their limbs, illustrated how their phantom legs felt.

Two years ago we

Two years ago we

Film-maker Noah Hutton has just released the ‘Year Four’

Film-maker Noah Hutton has just released the ‘Year Four’