Interest in the cognitive science of magic is really hotting up with Nature Neuroscience having just published a review article jointly authored by some leading cognitive scientists and stage illusionists. They argue that by studying magic, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention and awareness in the laboratory which could give insights into the neural basis of consciousness itself.

Interest in the cognitive science of magic is really hotting up with Nature Neuroscience having just published a review article jointly authored by some leading cognitive scientists and stage illusionists. They argue that by studying magic, neuroscientists can learn powerful methods to manipulate attention and awareness in the laboratory which could give insights into the neural basis of consciousness itself.

The neuroscientists involved are Stephen Macknik and Susana Martinez-Conde, while the magicians are Mac King, James Randi, Apollo Robbins, Teller from Penn and Teller, and John Thompson.

If this collection of names sounds familiar, it’s because this time last year the same group presented a symposium at the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness on ‘The Magic of Consciousness’.

The new article rounds up the conference discussion and The Boston Globe has a piece looking at some of the highlights.

This is not the only cognitive science article that explores what neuroscience can learn from the mystic arts. In a forthcoming article [pdf] for Trends in Cognitive Sciences psychologist Gustav Kuhn.

Kuhn has done some fantastic experimental studies looking at eye movements and attention of people watching magic tricks.

It’s not only an academic interest as Kuhn is apparently an illusionist himself and he’s one of a number of psychologists who also happen to be stage magicians. Just off the top of my head psychologists Richard Wiseman and Robert Moverman are also ex-professional conjurers. I’ve come across several others and so its perhaps not so surprising that these new articles have been published, but more that they took so long.

Both articles look at some common and no so common magic tricks and explain the cognitive science behind how they work:

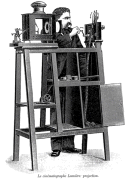

Persistence of vision is an effect in which an image seems to persist for longer than its presentation time12, 13, 14. Thus, an object that has been removed from the visual field will still seem to be visible for a short period of time. The Great Tomsoni’s (J.T.) Coloured Dress trick, in which the magician’s assistant’s white dress instantaneously changes to a red dress, illustrates an application of this illusion to magic. At first the colour change seems to be due (trivially) to the onset of red illumination of the woman. But after the red light is turned off and a white light is turned on, the woman is revealed to be actually wearing a red dress. Here is how it works: when the red light shuts off there is a short period of darkness in which the audience is left with a brief positive after-image of the red-dressed (actually white-dressed but red-lit) woman. This short after-image persists for enough time to allow the white dress to be rapidly removed while the room is still dark. When the white lights come back, the red dress that the assistant was always wearing below the white dress is now visible.

Link to Nature Neuroscience article (via BB).

pdf of Trends in Cognitive Science article.

Link to Boston Globe write-up.

The rather poetic

The rather poetic  Discover Magazine has a brief but interesting

Discover Magazine has a brief but interesting  Neurophilosophy has a fantastic

Neurophilosophy has a fantastic  This is a wonderfully written

This is a wonderfully written  As part of Seed Magazine’s on innovative thinkers in science, they published a podcast

As part of Seed Magazine’s on innovative thinkers in science, they published a podcast

The recently satirical New Yorker cover depicting Obama and his wife as fist-bumping Islamic terrorists comes under fire in an

The recently satirical New Yorker cover depicting Obama and his wife as fist-bumping Islamic terrorists comes under fire in an

I’m currently reading Elaine Showalter’s

I’m currently reading Elaine Showalter’s  The not very good photo is of Coco, the Maudsley Hospital cat and one in a long line of felines who reside in psychiatric hospitals. Not all psychiatric hospitals have cats, but they’re not uncommon and exist as a sort of informal tradition of live-in feline therapy.

The not very good photo is of Coco, the Maudsley Hospital cat and one in a long line of felines who reside in psychiatric hospitals. Not all psychiatric hospitals have cats, but they’re not uncommon and exist as a sort of informal tradition of live-in feline therapy. The results of a moderate sized trial on a new Alzheimer’s drug have just been

The results of a moderate sized trial on a new Alzheimer’s drug have just been  I’ve just found an eye-opening 2003

I’ve just found an eye-opening 2003  I just found this clever

I just found this clever  A new

A new