The man who discovered the Stroop effect and created the Stroop test, something which is now a keystone of cognitive science research, never realised the massive impact he had on psychology.

A short but fascinating news item from Vanderbilt University discusses its creator, the psychologist and preacher J. Ridley Stroop.

J. Ridley Stroop was born on a farm 40 miles from Nashville and was the only person in his family to attend college. He began preaching the gospel when he was 20 years old and continued to do so throughout his life. He spent nearly 40 years as a teacher and administrator at David Lipscomb College, now Lipscomb University, in Nashville….

According to his son, Stroop was unaware of the growing importance of his discovery when he died in 1973. Toward the end of his life, he had largely abandoned the field of psychology and immersed himself in Biblical studies. “He would say that Christ was the world’s greatest psychologist,” Faye Stroop recalled.

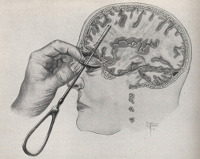

The task is very simple and relies on the fact that we automatically process word meaning when we see words. We don’t have to recognise each letter, consciously string them together, and ‘work out’ what word it is, it just happens straight away.

Stroop’s insight was to wonder what would happen if he asked people to do something that directly conflicted with this automatic processing.

So if I ask you to name the colour the following word is written in: blue; or name the colour this word is written in: red; you do it a little more slowly than naming the colour that these words are written in: blue, red.

This is because you have to inhibit or consciously ‘get round’ the word’s automatically recognised meaning.

This inhibition of automatic responses turns out to be a key function of attention and is heavily linked to the workings of the pre-frontal cortex.

There are many variations, all based on the fact that word meanings can relate to many different forms of psychological process, bias or experience.

For example, the ‘emotional Stroop‘ asks people to name the ‘ink colour’ of either emotionally neutral words (like ‘apple’, ‘soap’) and more emotionally intense words (like ‘violence’ or ‘torture’).

People who have been traumatised, will be more affected by these sorts of emotionally intense words and so they will identify the ‘ink colour’ of trauma-related words more slowly than when compared to non-traumatised people.

The same happens for people with spider phobia when they read spider-related words, and so on.

And because it allows experimenters to measure the interaction between attention and meaning, it has become a massively useful and popular tool.

Link to piece on the history of the Stroop task.

The Psychologist has a fascinating

The Psychologist has a fascinating

Regular readers will know of my ongoing fascination with the fate of the old psychiatric asylums and how they’re often turned into luxury apartments with not a whisper of their previous life.

Regular readers will know of my ongoing fascination with the fate of the old psychiatric asylums and how they’re often turned into luxury apartments with not a whisper of their previous life. Aeon Magazine has an amazing

Aeon Magazine has an amazing

Spiegel Online has an excellent

Spiegel Online has an excellent  We tend to think of Prozac as the first ‘fashionable’ psychiatric drug but it turns out popular memory is short because a tranquilizer called

We tend to think of Prozac as the first ‘fashionable’ psychiatric drug but it turns out popular memory is short because a tranquilizer called

The New York Times

The New York Times