After amputation, many people feel ‘phantom limb‘ sensations that seem to come from the missing body part. Although typically associated with missing arms or legs, these phantom sensations can arise from almost anywhere and a new study in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences looks at how the ‘phantom penis’ has enjoyed a surprisingly long history in the medical literature.

After amputation, many people feel ‘phantom limb‘ sensations that seem to come from the missing body part. Although typically associated with missing arms or legs, these phantom sensations can arise from almost anywhere and a new study in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences looks at how the ‘phantom penis’ has enjoyed a surprisingly long history in the medical literature.

The first case of a phantom penis was mentioned in passing by the ‘father’ of phantom limbs, Silas Weir Mitchell, and there has been an assumption that these sensations are rare or unusual.

In fact, a 1999 case report of a phantom penis after amputation noted only a few previous mentions of the experience, some of which have become quite well-known.

Among the most cited publications is one by Boston surgeon A. Price Heusner (1950) containing two case studies. His first case was an elderly man whose penis was “accidently traumatized and amputated,” and who “was intermittently aware of a painless but always erect penile ghost whose appearances were neither provoked nor provokable by sexual phantasies” (Heusner, 1950, p. 129). This man had to look under his clothes to be sure that his penis was, in fact, absent. Heusner’s second case was a middle-aged, perineal cancer patient. Because his malignancy had spread and was causing intense burning pains in his groin, he opted to undergo penile amputation. Thereafter, he continued to have painful sensations “suggesting the continuing presence of the penis,” until he underwent spinal surgery

This new historical study shows that there were actually many reports of phantom penises in the 18th Century medical literature that have previously been overlooked.

These include reports from some of the most important doctors of the time, and indeed, some of the most important in history.

This included the Scottish surgeon and anatomist John Hunter who reported on what can only be described as phantom wanking:

A serjeant of marines who had lost the glans, and the greater body of the penis, upon being asked, if he ever felt those sensations which are peculiar to the glans, declared, that upon rubbing the end of the stump, it gave him exactly the sensation which friction upon the glans produced, and was followed by an emission of the semen.

Hunter’s case highlights an interesting aspect of the phantom penis sensation which seems to differentiate it from most other forms of phantom limb sensations – they tend to be pleasurable rather than painful.

Phantom limbs are often associated with the feeling that the missing body part is stuck in an awkward position, such as the ‘fingers digging into the palm’, something which the mirror box treatment attempts to correct.

Although some painful phantom penises have been reported they seem more likely to appear as pleasurable sensations and phantom erections.

This may have some interesting implications for neuroscience. Phantom limbs are thought to arise when activity in the brain maps that represent the limbs no longer have a constant flow of sensory feedback that keep them tied to their task.

The boundaries of the maps become blurry and information from other body areas starts to cause activity in the map for the missing limb, leading to the phantom sensations.

However, in contrast to the penis, arms and legs involve much more of a feedback loop, because fine action control signals are being sent and modified on the basis of the sensations from the limb.

As the penis has less need for such fine action control, it’s probably less likely that misfiring of the signals can make it seem as if it is in an awkward or painful position, possibly reducing the chance of an uncomfortable phantom pecker.

Link to DOI entry for the locked article (via AITHOP).

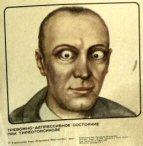

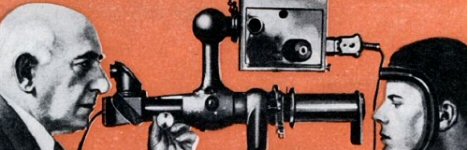

Legendary Polish neurologist Edward Flatau created one of the first photographic brain atlases way back in 1894. This photo shows how he carefully took 20-minute exposure photos of freshly sliced brains.

Legendary Polish neurologist Edward Flatau created one of the first photographic brain atlases way back in 1894. This photo shows how he carefully took 20-minute exposure photos of freshly sliced brains. A wonderful poem simply titled ‘Thought’ by the English writer

A wonderful poem simply titled ‘Thought’ by the English writer  Some of the world’s best illusionists are now

Some of the world’s best illusionists are now  English Russia has a

English Russia has a

The Psychologist has a fascinating

The Psychologist has a fascinating  The Loom has a wonderful

The Loom has a wonderful

I often get asked what ‘nervous breakdown’ means, as if it was a technical term defined by psychology.

I often get asked what ‘nervous breakdown’ means, as if it was a technical term defined by psychology.

Yale University archives have a piece of steak signed by the famous Russian psychologist

Yale University archives have a piece of steak signed by the famous Russian psychologist  A 1997

A 1997