As the cacophony of politicians and commentators replaces that of the police sirens, look out for the particularly shrill voice of those who condemn as evil anyone with an alternative explanation for the looting than theirs. For an example, take the Daily Mail headline for Tuesday, which reads “To blame the cuts is immoral and cynical. This is criminality pure and simple”

If I’ve got them right, this means that when considering what factors contributed to the looting, identifying government spending cuts is not just incorrect, but actively harmful. For the Mail, the issue of explanations for the looting is of such urgency that they are comfortable condemning anyone who seeks an explanation beyond that of the looting being “criminality pure and simple”. What could be motivating this?

Research into moral psychology provides a lead. One of my favourite papers is “Thinking the unthinkable: sacred values and taboo cognitions” by Philip Tetlock (2003). In this paper he talks about how our notion of the sacred affect our thinking. The argument he makes is that in all cultures some values are sacred and we are motivated to not just to punish people who offend against these values, but also to punish people who even think about offending these values. The key experiment, from Tetlock et al, 2000, concerns a vignette about a sick child and hospital manager, who must decided if the hospital budget can afford an expensive treatment for the sick child. After reading about the manager’s decision, participants in the experiment are given the option to say how they felt about the manager, and to answer questions about such things as whether they think he should be removed from his job, and whether, if he were a friend of theirs, they would end their friendship with him. Unsurprisingly, if the vignette concludes by revealing that the manager decided the treatment was too expensive, participants are more keen to punish the manager than if he decided that the hospital could afford to treat the child. The explanation in terms of sacred values is straightforward: life, especially the life of a child, is a sacred value; money is not and so should not be weighed against the sacred value of life. But the most interesting contrast in the experiment is between participants who read vignettes in which the manager took a long time to make his decision and those in which he didn’t. Regardless of whether he decided for or against paying for the treatment, reading that the manager thought for a long time before making a decision provoked participants to want to punish the manager more. Tetlock argues that we are motivated to punish not just those who offend against sacred values, but also those who appear to be thinking about offending against sacred values – by weighing them against non-sacred values. In an added twist, Tetlock and colleagues also offered participants the opportunity to engage in ‘moral cleansing’ by subscribing to an organ donation scheme. Those participants who read about the manager who chose to save the money over saving the child, and those who read about the manager who took a long time to make his decision, regardless of what it was, were most motivated to donate their organs. This shows, Tetlock argues, that it is merely enough for the idea of breaking a taboo to flicker across your consciousness to provoke feelings of disgust at ourselves (which provoke the need for moral cleansing).

Tetlock’s papers are a full and nuanced treatment of how sacred values and taboo cognitions affect our thinking. I have only presented a snapshot here, and can but recommend that you read the full papers yourself, but I’d like to break from the science to draw some fairly obviously conclusions.

The Daily Mail editors feel they are in a moral community in which society is threatened by the looters and by those who give them succour, ‘the handwringing apologists on the Left’ who ‘blame the violence on poverty, social deprivation and a disaffected…youth’ (to quote from the rest of Tuesday’s editorial). For some, the looting is an immoral act of such a threatening nature that to think about it too hard, to react with anything other than a vociferous condemnation, is itself worthy of condemnation.

The sad thing about adopting this stance is that it prevents media commentators from thinking about how they themselves might have contributed to the looting. The footage on TV and in newspapers such as the Daily Mail has been vivid and hysterical. Television has shown the most dramatic footage of the looting, while headlines have screamed about the police losing control and anarchy on the streets. You don’t have to be a scholar of psychology to realise that this kind of media environment might play a role in encouraging the copycat looting sprees that sprung up outside of London (although if you were, you would be aware of the literature on how newspaper headlines and TV footage, can provoke immitation in the wider population).

Some, like the Daily Mail, see any attempt at explaining the looting as excusing the looting. The looting, like so much for them, is a moral issue of such virulence that they see people who understand society differently as part of the same threat to society as the looters. Research in moral psychology provides some clues about their style of thinking. It doesn’t, as far as I know, provide much of a clue about how to alter it.

REFS

Tetlock, P. E. (2003). Thinking the unthinkable: Sacred values and taboo cognitions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(7), 320–324.

Tetlock, P.E. et al. (2000) The psychology of the unthinkable: taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 853– 870

See also Vaughan’s Riot Psychology

Language Log

Language Log

I’ve written an

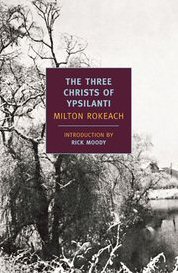

I’ve written an  The New York Review of Books has just

The New York Review of Books has just

Not Exactly Rocket Science

Not Exactly Rocket Science  Both of this year’s lead Oscar winners have published scientific papers on neuroscience. We’ve

Both of this year’s lead Oscar winners have published scientific papers on neuroscience. We’ve  Delusions in conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have tracked social concerns over the 20th century, according to a wonderful

Delusions in conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have tracked social concerns over the 20th century, according to a wonderful

A gripping

A gripping  The illusion that a horse could do maths may be behind sniffer dogs falsely ‘detecting’ illicit substances according to an intriguing study

The illusion that a horse could do maths may be behind sniffer dogs falsely ‘detecting’ illicit substances according to an intriguing study