If you want any evidence that drugs have won the drug war, you just need to read the scientific studies on legal highs.

If you want any evidence that drugs have won the drug war, you just need to read the scientific studies on legal highs.

If you’re not keeping track of the ‘legal high’ scene it’s important to remember that the first examples, synthetic cannabinoids sold as ‘Spice’ and ‘K2’ incense, were only detected in 2009.

Shortly after amphetamine-a-like stimulant drugs, largely based on variations on pipradrol and the cathinones appeared, and now ketamine-like drugs such as methoxetamine have become widespread.

Since 1997, 150 new psychoactive substances were reported. Almost a third of those appeared in 2010.

Last year, the US government banned several of these drugs although the effect has been minimal as the legal high laboratories have over-run the trenches of the drug warriors.

A new study just published in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology tracked the chemical composition of legal highs as the bans were introduced.

A key question was whether the legal high firms would just try and use the same banned chemicals and sell them under a different name.

The research team found that since the ban only 4.9% of the products contained any trace of the recently banned drugs. The remaining 95.1% of products contained drugs not covered by the law.

The chemicals in legal highs have fundamentally changed since the 2011 ban and the labs have outrun the authorities in less than a year.

Another new study has looked at legal highs derived from pipradrol – a drug developed in 1940s for treating obesity, depression, ADHD and narcolepsy.

It was made illegal in many countries during the 70s due to its potential for abuse because it gives an amphetamine-like high.

The study found that legal high labs have just been running through variations of the banned drug using simple modifications of the original molecule to make new unregulated versions.

The following paragraph is from this study and even if you’re not a chemist, you can get an impression of how the drug is been tweaked in the most minor ways to create new legal versions.

Modifications include: addition of halogen, alkyl or alkoxy groups on one or both of the phenyl rings or addition of alkyl, alkenyl, haloalkyl and hydroxyalkyl groups on the nitrogen atom. Other modifications that have been reported include the substitution of a piperidine ring with an azepane ring (7-membered ring), a morpholine ring or a pyridine ring or the fusion of a piperidine ring with a benzene ring. These molecules, producing amphetamine-like effects, increase the choice of new stimulants to be used as legal highs in the coming years.

New, unknown and poorly understood psychoactive chemicals are appearing faster than they can be regulated.

The market is being driven by a demand for drugs that have the same effects as existing legal highs but won’t get you thrown in prison.

The drug war isn’t only being lost, it’s being made obsolete.

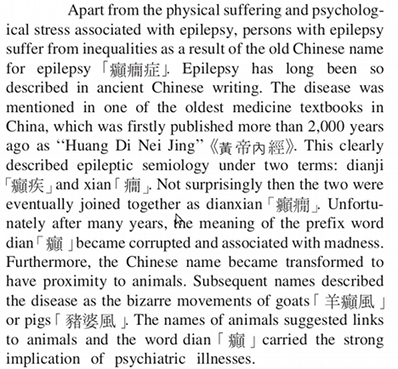

The Chinese character for

The Chinese character for  just makes reference to the brain although the story of how the original name got its meaning is quite fascinating in itself.

just makes reference to the brain although the story of how the original name got its meaning is quite fascinating in itself.

A group of black bloc researchers fed up with the lack of interest in replicating psychology studies has set up a strike force called the

A group of black bloc researchers fed up with the lack of interest in replicating psychology studies has set up a strike force called the  Nature has an

Nature has an  The Ailing Brain is a fantastic documentary series on the brain and its disorders that’s freely available online. It has been produced in Spanish but the

The Ailing Brain is a fantastic documentary series on the brain and its disorders that’s freely available online. It has been produced in Spanish but the

This year’s Royal Institution Christmas Lectures were a fantastic trip through neuroscience and the brain – and you can now watch them

This year’s Royal Institution Christmas Lectures were a fantastic trip through neuroscience and the brain – and you can now watch them  The American Psychiatric Association have used

The American Psychiatric Association have used