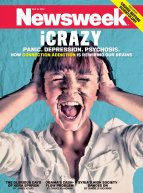

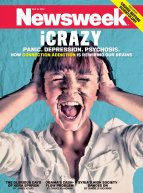

Oh Newsweek, what have you done. The cover story in the latest edition is an embarrasing look at non-research that certainly doesn’t suggest that the internet is causing “extreme forms of mental illness”.

Oh Newsweek, what have you done. The cover story in the latest edition is an embarrasing look at non-research that certainly doesn’t suggest that the internet is causing “extreme forms of mental illness”.

The article is a litany of scientific stereotypes and exaggeration:

The current incarnation of the Internet—portable, social, accelerated, and all-pervasive—may be making us not just dumber or lonelier but more depressed and anxious, prone to obsessive-compulsive and attention-deficit disorders, even outright psychotic.

This is an amazing list of mental illnesses supposedly caused by the internet but really Newsweek? Psychosis? A condition ranked by the World Health Organisation as the third most disabling health condition there is and one that is only beaten in its ability to disable by total limb paralysis and dementia and that comes ahead of leg paralysis and blindness.

We’re talking schizophrenia and severe bipolar disorder here. The mention of psychosis even makes the front page, of one of the most respected news magazines in the world, so this must be pretty striking evidence.

So striking, in fact, that it would probably turn psychiatric research on its head. We have studied the environmental risk factors for psychosis for decades and nothing has suggested that the internet or anything like it would raise the risk of psychosis. This must be amazing new scientific evidence.

So what is the evidence to back up Newsweek’s front page splash: a blog post, a quote and a single case study.

The rest of the article is full of similar howlers.

But the research is now making it clear that the Internet is not “just” another delivery system. It is creating a whole new mental environment, a digital state of nature where the human mind becomes a spinning instrument panel, and few people will survive unscathed.

“This is an issue as important and unprecedented as climate change,” says Susan Greenfield, a pharmacology professor at Oxford Univer…

Oh Christ.

A 1998 Carnegie Mellon study found that Web use over a two-year period was linked to blue moods, loneliness, and the loss of real-world friends. But the subjects all lived in Pittsburgh, critics sneered.

They didn’t sneer. They looked at the follow-up study, done on the same people, by the same research team, that found that “A 3-year follow-up of 208 of these respondents found that negative effects dissipated”.

As I’ve mentioned before, it is only possible to report on the first of these findings without the second if you’ve not read the research or are aiming for a particular angle. Why? Because if you type ‘internet paradox’, the name of the original study, into Google, the name of the follow-up study – The Internet Paradox Revisited – comes up as the second link.

If you’d read any of the actual literature on the topic, you’d know about the follow-up study because they are two of the most important and some of the few longitudinal studies in the field.

The article also manages the usual neuroscience misunderstandings. The internet ‘rewires the brain’ – which I should hope it does, as every experience ‘rewires the brain’ and if your brain ever stops re-wiring you’ll be dead. Dopamine is described as a reward, which is like mistaking your bank statement for the money.

There are some scattered studies mentioned here and there but without any sort of critical appraisal. Methodological problems with internet addiction studies? No mention. The fact that the whole concept of internet addiction is a category error? Not a whisper. The fact that prevalence has been estimated to vary between 1% and 66% of internet users. Nada

Sadly, these sorts of distorted media portrayals have a genuine impact on the public’s attitudes and beliefs about mental illness.

But perhaps the biggest problem with the article is that it doesn’t include any critical voices. It’s mainly people who have a book to sell or an axe to grind.

The internet will apparently make you psychotic if you only listen to the three people who think so. Or Newsweek, that is.

Link to ‘Is the Web Driving Us Mad?’

Science writer

Science writer  It’s not often you see someone licking a brain in a rock n’ roll video and get to think to yourself “well, there’s a funny story behind that”, but this is one of those occasions.

It’s not often you see someone licking a brain in a rock n’ roll video and get to think to yourself “well, there’s a funny story behind that”, but this is one of those occasions.

In a

In a

The latest FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin is a

The latest FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin is a  Oh Newsweek, what have you done. The

Oh Newsweek, what have you done. The