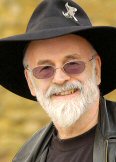

I’ve just found an amazing Terry Pratchett article published in the Journal of Mental Health earlier this year entitled ‘Diagnosing Clapham Junction syndrome’ where he discusses his experience with dementia.

I’ve just found an amazing Terry Pratchett article published in the Journal of Mental Health earlier this year entitled ‘Diagnosing Clapham Junction syndrome’ where he discusses his experience with dementia.

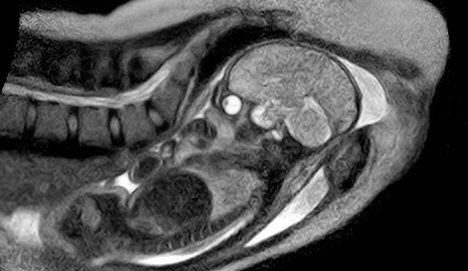

Pratchett was diagnosed with posterior cortical atrophy, usually considered to be an atypical form of Alzheimer’s disease that is focused on the back of the brain and tends to cause particular disruption to visual abilities.

You can’t battle it, you can’t be a plucky “survivor”. It just steals you from yourself. And I’m 60; that’s supposed to be the new 40. The baby boomers are getting older, and will stay older for longer. And they will run right into the dementia firing range. How will a society cope? Especially a society that can’t so readily rely on those stable family relationships that traditionally provided the backbone of care?

What is needed is will and determination. The first step is to talk openly about dementia because it’s a fact, well enshrined in folklore, that if we are to kill the demon then first we have to say its name. Once we have recognized the demon, without secrecy or shame, we can find its weaknesses. Regrettably one of the best swords for killing demons like this is made of gold – lots of gold. These days we call it funding. I believe the D-day battle on Alzheimer’s will be engaged shortly and a lot of things I’ve heard from experts, not always formally, strengthen that belief. It’s a physical disease, not some mystic curse; therefore it will fall to a physical cure. There’s time to kill the demon before it grows.

I have to say, in one section, Pratchett is probably a little hard on clinicians in terms of how long it takes to diagnose dementia, which is not an easy task.

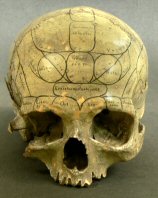

Dementia is usually defined as a decline in mental abilities that happens faster than would be expected from normal ageing and is associated with degeneration of the brain.

There are many types of dementia, and diagnosis is often broken down into ‘possible’, ‘probable’ and ‘confirmed’ versions.

Rather frustratingly, for those wanting a precise and confident diagnosis of, let’s say, Alzheimer’s disease, a ‘confirmed’ diagnosis can only be officially made on the basis of close examination of the brain tissue after the symptoms are known.

In practice this means that dementia can only be ‘confirmed’ after death. The result is that most people get a diagnosis of ‘possible’ or ‘probable’ dementia.

The former is made when the person has known cognitive problems and estimates that they were much better before, and the latter only when testing has shown that there has been a definite decline over at least six months.

For a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, this needs to affect at least two areas of mental functioning, so a tried and tested decline in just memory over six months would still leave some doubt. This means a wait of a year can be pretty standard for a ‘probable’ diagnosis.

After finally getting his diagnosis after experiencing difficulties for some time, Pratchett says “you could have used my anger to weld steel”. It’s worth saying that the frustration is shared.

By the way, Pratchett’s article was published in a special open-access edition of the Journal of Mental Health focussing on classification where several people discuss their experience of hearing their diagnosis.

There’s a particularly good piece by Mark Vonnegut, son of science fiction author Kurt Vonnegut who was previously diagnosed with schizophrenia and is now a qualified doctor, working as a primary care pediatrician.

Link to Terry Pratchett on ‘Diagnosing Clapham Junction syndrome’.

Link to table of content for open-access edition.

I’ve just found an amazing Terry Pratchett

I’ve just found an amazing Terry Pratchett  Slate has an amazing

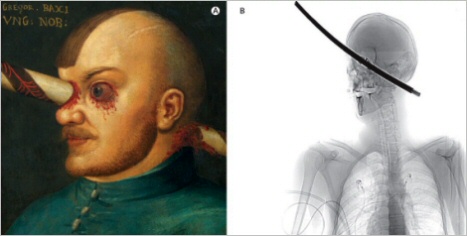

Slate has an amazing  Legendary Polish neurologist

Legendary Polish neurologist  The Guardian has an excellent

The Guardian has an excellent

This week’s

This week’s  I’ve just read an incredible

I’ve just read an incredible  I’ve just discovered a new

I’ve just discovered a new

BBC Radio 4 recently ran a fascinating one-off

BBC Radio 4 recently ran a fascinating one-off  All in the Mind kicks off a new three-part series on ‘Cultural Chemistry’ with a

All in the Mind kicks off a new three-part series on ‘Cultural Chemistry’ with a  Bad Science has an excellent

Bad Science has an excellent  The Loom has a wonderful

The Loom has a wonderful