‘Is pornography driving men crazy?’ asks campaigner Naomi Wolf in a CNN article that contains a spectacular misunderstanding of neuroscience applied to a shaky moral conclusion.

‘Is pornography driving men crazy?’ asks campaigner Naomi Wolf in a CNN article that contains a spectacular misunderstanding of neuroscience applied to a shaky moral conclusion.

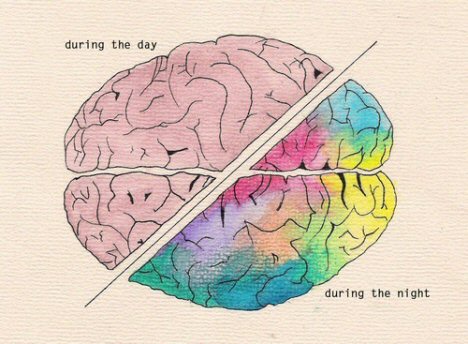

Wolf asks suggests that the widespread availability and consumption of pornography is “rewiring the male brain” and “causing them to have more difficulty controlling their impulses”.

According to her article, pornography causes “rapid densensitization” to sexual stimulation which is “desensitizing healthy young men to the erotic appeal of their own partners” and means “ordinary sexual images eventually lose their power, leading consumers to need images that break other taboos in other kinds of ways, in order to feel as good.”

Moreover, she says “some men (and women) have a “dopamine hole” – their brains’ reward systems are less efficient – making them more likely to become addicted to more extreme porn more easily.”

Wolf cites the function of dopamine to back up her argument and says this provides “an increasing body of scientific evidence” to support her ideas.

It does not, and unfortunately, Wolf clearly does not understand either the function or the relevance of the dopamine system to this process, but we’ll get onto that in the moment.

Purely on the premise of the article, I was troubled by the fact that “breaking taboos” is considered to be a form of pathology and it lumps any sort of progression in sexual interest as a move toward the “extreme”.

‘Taboo’ and ‘extreme’ are really not the issue here as both are a matter of perception and taste. What is important is ‘consensual’ and ‘non-consensual’ and when the evidence is examined as a whole there is no conclusive evidence that pornography increases sexual violence or the approval of it (cross-sectional studies tend to find a link, experimental and crime data studies do not).

To the contrary, wanting new and different sexual experiences is for the majority a healthy form of sexual exploration, whether that be through porn or other forms of sexual behaviour.

One part of the motivation for this is probably that people do indeed become densensitised to specific sexual images or activities, so seeing the same thing or doing the same thing over and over is likely to lead to boredom – as any women’s magazine will make abundantly clear on their advice pages.

But this is no different to densensitisation to any form of emotional experience. I contacted Jim Pfaus, the researcher mentioned in the article, who has conducted several unpublished studies showing that physiological arousal reduces on repeat viewing of sexual images, but he agrees that this is in line with standard habituation of arousal to most type of emotional images, not just sexual, that happens equally with men and with women.

It’s important to point out that this densensitisation research is almost always on the repetition of exactly the same images. We would clearly be in trouble if any sexual experience caused us to densensitise to sex as we’d likely lose all interest by our early twenties.

However, it is Wolf’s description of the dopamine system where things get really weird:

Since then, a great deal of data on the brain’s reward system has accumulated to explain this rewiring more concretely. We now know that porn delivers rewards to the male brain in the form of a short-term dopamine boost, which, for an hour or two afterwards, lifts men’s mood and makes them feel good in general. The neural circuitry is identical to that for other addictive triggers, such as gambling or cocaine.

The addictive potential is also identical: just as gamblers and cocaine users can become compulsive, needing to gamble or snort more and more to get the same dopamine boost, so can men consuming pornography become hooked. As with these other reward triggers, after the dopamine burst wears off, the consumer feels a letdown – irritable, anxious, and longing for the next fix.

Wolf is accidentally right when she says that porn ‘rewires the brain’ but as everything rewires the brain, this tells us nothing.

With regard to dopamine, it is indeed involved in sexual response, but this is not identical to the systems involved with gambling or cocaine as different rewards rely on different circuits in the brain – although doesn’t it sound great to lump those vices together?

Porn is portrayed as a dangerous addictive drug that hooks naive users and leads them into sexual depravity and dysfunction. The trouble is, if this is true (which by the way, it isn’t, research suggests both males and females find porn generally enhances their sex lives, it does not effect emotional closeness and it is not linked to risky sexual behaviours) it would also be true for sex itself which relies on, unsurprisingly, a remarkably similar dopamine reward system.

Furthermore, Wolf relies on a cartoon character version of the reward system where dopamine squirts are represented as the brain’s pleasurable pats on the back.

But the reward is not the dopamine. Dopamine is a neurochemical used for various types of signalling, none of which match the over-simplified version described in the article, that allow us to predict and detect rewards better in the future.

One of its most important functions is reward prediction where midbrain dopamine neurons fire when a big reward is expected even when it doesn’t occur – such as in a near-miss money-loss when gambling – a very unpleasant experience.

But what counts as a reward in Wolf’s dopamine system stereotype? Whatever makes the dopamine system fire. This is a hugely circular explanation and it doesn’t account for the huge variation in what we find rewarding and what turns us on.

This is especially important in sex because people are turned on by different things. Blondes, brunettes, men, women, transsexuals, feet, being spanked by women dressed as nuns (that list is just off the top of my head you understand).

Not all sex is rewarding to all people and people have their likes, dislikes and limits.

In other words, there is more to reward than the dopamine system and in many ways it is a slave to the rest of the brain which interprets and seeks out the things we most like. It is impossible to explain sexual motivation or sexual pathology purely or, indeed, mainly as a ‘dopamine problem’.

Wolf finishes by saying that “understanding how pornography affects the brain and wreaks havoc on male virility permits people to make better-informed choices” despite clearly not understanding how pornography could affect the brain and providing nothing but anecdotes about the effect on male sexual function.

This does not mean all porn is helpful or healthy, either to individuals or society, but we should be criticising it on established effects, not on misunderstood and poorly applied neuroscience deployed in the service of bolstering shaky conclusions about its personal impact.

Link to Naomi Wolf’s “Is pornography driving men crazy?”

A mysterious epidemic of paralysis was sweeping through 1920s America that had the medical community baffled. The cause was first identified not by physicians, but by blues singers.

A mysterious epidemic of paralysis was sweeping through 1920s America that had the medical community baffled. The cause was first identified not by physicians, but by blues singers. The New York Times has an inspiring

The New York Times has an inspiring

A team of neurosurgeons has completed an exhaustive

A team of neurosurgeons has completed an exhaustive  BBC Radio 4’s Crossing Continents has an excellent

BBC Radio 4’s Crossing Continents has an excellent  Nature News has an excellent

Nature News has an excellent  The New York Times has an amazing

The New York Times has an amazing

I’ve got a brief

I’ve got a brief  A

A

The San Francisco Chronicle has a striking

The San Francisco Chronicle has a striking