The judge in the case of ‘Colorado shooter’ James Holmes has made the baffling decision that a ‘narcoanalytic interview’ and ‘polygraph examination’ can be used in an attempt to support an insanity plea.

The judge in the case of ‘Colorado shooter’ James Holmes has made the baffling decision that a ‘narcoanalytic interview’ and ‘polygraph examination’ can be used in an attempt to support an insanity plea.

While polygraph ‘lie detectors’ are known to be seriously flawed, some US states still allow evidence from them to be admitted in court although the fact they’re being considered in such a key case is frankly odd.

But the ‘narcoanalytic interview’ is so left-field as to leave some people scratching their heads as to whether the judge has been at the narcotics himself.

The ‘narcoanalytic interview’ is sometimes described as the application of a ‘truth drug’ but the actual practice is far more interesting.

It has been variously called ‘narcoanalysis’, ‘narcosynthesis’ and the ‘amytal interview’ and involves, as you might expect, interviewing the person under the influence of some sort of narcotic.

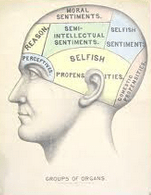

It’s roots lie in the very early days of 1890s pre-psychoanalysis where Freud used hypnosis to relax patients to help them discuss emotionally difficult matters.

The idea that being relaxed overcame the mind’s natural resistance to entertaining difficult thoughts and helped get access to the unconscious became the foundation of Freud’s work. Narcoanalysis is still essentially based on this idea.

But, of course, the concept had to wait until the discovery of the first suitable drugs – the barbituates.

Psychiatrist William Bleckwenn found that giving barbital to patients with catatonic schizophrenia led to a “lucid interval” where they seemed to be able to discuss their own mental state in a way previously impossible.

You can see the parallels in the first ever use of ‘narcoanalysis’ to the current case, but through the rest of the century the concept merged with the idea of creating a “truth drug”.

This was born in the 1920s where the gynaecologist Robert House noticed that women who were given scopolamine to ease the birth process seemed to go into a ‘twilight state’ and were more pliant and talkative.

House decided to test this on criminals and went about putting prisoners under the influence of the drug while interviewing them as a way of ‘determining innocence or guilt’. Encouraged by some initial, albeit later recanted, confessions House began to claim that it should be used routinely in police investigations.

This probably would have died a death as a dubious medical curiosity had Time magazine not run an article in their 1923 edition entitled “The Truth-Compeller” about House’s theory – making him and the ‘truth drug’ idea national stars.

These approaches became militarised: firstly as ‘narcoanalysis’ was used to treat traumatised soldiers in the World War Two, and secondly as it was taken up by the CIA in the Cold War as a method for interrogation and became a centrepiece of the secret Project MKUltra.

It has continued to be used in criminal investigations in the US, albeit infrequently, although it has popped up in the legal rulings.

In 1985 the US Supreme Court rejected an appeal by two people convicted of murder that their ‘narcoanalysis police interview’ made their conviction unsafe.

However, the psychiatrist who conducted the interview didn’t convince any of the judges that ‘narcoanalysis’ was actually of benefit:

At one point he testified that it would elicit an accurate statement of subjective memory, but later said that the subject could fabricate memories. He refused to agree that the subject would be more likely to tell the truth under narcoanalysis than if not so treated.

The concept seemed to disappear after that but strong suspicions were raised that ‘narcoanalysis’ was still a CIA favourite when the Bush government’s infamous ‘torture memo‘ justified the use of “mind-altering substances” as part of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’.

There is no evidence that ‘narcoanalysis’ actually helps in any way, shape or form, and at moderate to high doses, some of the drugs may actually impede memory or make it more likely that the person misremembers.

I suspect that the actual result of the bizarre ruling in the ‘Colorado shooter’ case will just be that psychiatrists will be able to give a potentially psychotic suspect a simple anti-anxiety drug without the resulting evidence being challenged.

This would be no different than giving an anxious or agitated witness the same drug to help them recount what happened.

But the fact that the judge included ‘lie detectors’ and ‘narcoanalysis’ in his ruling as useful legal tools rather than recognising them as flawed investigative techniques is still very concerning and suggests legal thinking mired in the 1950s.

pdf of judge’s ruling.

Link to (ironically locked) article on the history of ‘narcoanalysis’

If you only listen to one radio programme this week, make it the latest edition of BBC Radio 4’s Analysis on the under-explored science of gender.

If you only listen to one radio programme this week, make it the latest edition of BBC Radio 4’s Analysis on the under-explored science of gender.

I’ve written a

I’ve written a

Stanford Magazine has a wonderful

Stanford Magazine has a wonderful  I’ve got a

I’ve got a  The Guardian has a

The Guardian has a

The heaving busts and melodrama of a Latin American soap opera, a television industry desperate for a ratings hit, and the writer makes a woman with

The heaving busts and melodrama of a Latin American soap opera, a television industry desperate for a ratings hit, and the writer makes a woman with  Two neuroscience projects have been earmarked for billion dollar funding by Europe and the US government but little has been said about what the projects will achieve. Here’s what we know.

Two neuroscience projects have been earmarked for billion dollar funding by Europe and the US government but little has been said about what the projects will achieve. Here’s what we know.