The idea of the ‘hot hand’, where a player who makes several successful shots has a higher chance of making some more, is popular with sports fans and team coaches, but has long been considered a classic example of a cognitive fallacy – an illusion of a ‘streak’ caused by our misinterpretation of naturally varying scoring patterns.

The idea of the ‘hot hand’, where a player who makes several successful shots has a higher chance of making some more, is popular with sports fans and team coaches, but has long been considered a classic example of a cognitive fallacy – an illusion of a ‘streak’ caused by our misinterpretation of naturally varying scoring patterns.

But a new study has hard data to show the hot hand really exists and may turn one of the most widely cited ‘cognitive illusions’ on its head.

A famous 1985 study by psychologist Thomas Gilovich and his colleagues looked at the ‘hot hand’ belief in basketball, finding that there was no evidence of any ‘scoring streak’ in thousands of basketball games beyond what you would expect from natural variation in play.

Think of it like tossing a weighted coin. Although the weighting, equivalent to the players skill, makes landing a ‘head’ more likely overall, every toss of the coin is independent. The last result doesn’t effect the next one.

Despite this, sometimes heads or tails will bunch together and this is what people erroneously interpret as the ‘hot hand’ or being on a roll, at least according to the theory. Due to the basketball research, that seemed to show the same effect, the ‘hot hand fallacy’ was born and the idea of ‘scoring streaks’ thought to be sports myth.

Some have suggested that while the ‘hot hand’ may be an illusion, in practical terms, in might be useful on the field.

Better players are more likely to have a higher overall scoring rate and so are more likely to have what seem like streaks. Passing to that guy works out, because the better players have the ball for longer.

But a new study led by Markus Raab suggests that the hot hand does indeed exist. Each shot is not independent and players that hit the mark may raise their chances of scoring the next time. They seem to draw inspiration from their successes.

Crucially, the researchers chose their sport carefully because one of the difficulties with basketball – from a numbers point of view – is that players on the opposing team react to success.

If someone scores, they may find themselves the subject of more defensive attention on the court, damping down any ‘hot hand’ effect if it did exist.

Because of this, the new study looked at volleyball where the players are separated by a net and play from different sides of the court. Additionally, players rotate position after every rally, meaning its more difficult to ‘clamp down’ on players from the opposing team if they seem to be doing well.

The research first established the belief in the ‘hot hand’ was common in volleyball players, coaches and fans, and then looked to see if scoring patterns support it – to see if scoring a point made a player more likely to score another.

It turns out that over half the players in Germany’s first-division volleyball league show the ‘hot hand’ effect – streaks of inspiration were common and points were not scored in an independent ‘coin toss’ manner.

What’s more, players were sensitive to who was on a roll and used the effect to the team’s advantage – more commonly passing to those on a scoring streak.

So it seems the ‘hot hand’ effect exists. But this opens up another, perhaps more interesting, question.

How does it work? Because if teams can understand the essence of on court inspiration, they’ve got a recipe for success.

Link to blocked study. Clearing a losing strategy.

Link to full text which has mysteriously appeared online.

I’ve written an in-depth

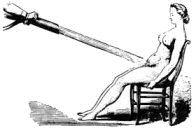

I’ve written an in-depth  We’ve covered The Technology of Orgasm

We’ve covered The Technology of Orgasm  The New York Times has an

The New York Times has an  Perhaps the most complete scientific review of what we know about synthetic cannabis or ‘spice’ products has just

Perhaps the most complete scientific review of what we know about synthetic cannabis or ‘spice’ products has just  An article in the Journal of Medical Humanities has a fascinating look at one of playwright

An article in the Journal of Medical Humanities has a fascinating look at one of playwright

A beautifully recursive

A beautifully recursive  Scientific American’s Bering in Mind has a fantastic

Scientific American’s Bering in Mind has a fantastic