My BBC Future column from Tuesday. The original is here. It’s a Christmas theme folks, but hopefully I cover an interesting research area too: Berridge, Robinson and colleagues’ work on the wanting/liking distinction.

As the holiday season approaches, Tom Stafford looks at festive overindulgence, and explains how our minds tell us we want something even if we may not like it.

Ah, Christmas, the season of peace, goodwill and overindulgence. If this year is like others, I’ll probably be taking up residence on the couch after a big lunch, continuing to munch my way through packets of unhealthy snacks, and promising myself that I’ll live a more virtuous life once the New Year begins.

It was on one such occasion that I had an epiphany in the psychology of everyday life. I’d just finished the last crisp of a large packet, and the thought occurred to me that I don’t actually like crisps that much. But there I was, covered in crumbs and post-binge guilt, saturated fats coursing through my body looking for nice arteries to settle down on. In an effort to distract myself from the urge to reach for another packet, I started to think about the peculiar psychology of the situation.

Every bite seemed essential, but in a way that seem to suggest I was craving them rather than liking them. Fortunately for my confusion (and my arteries), there’s some solid neuroscience to explain how we can want something we don’t like.

Normally wanting and liking are tightly bound together. We want things we like and we like the things we want. But experiments by the University of Michigan’s Kent Berridge and colleagues show that this isn’t always the case. Wanting and liking are based on separate brain circuits and can be controlled independently.

To demonstrate this, Berridge used a method called “taste reactivity“, in effect, recording the faces pulled when animals are given different kinds of food. Give an adult human something sweet and they’ll lick their lips. This might sound obvious, but when you take it to the next level in terms of detail and rigour you start to get a powerful system for telling how much an animal likes a particular type of food. Taste reactivity involves defining the reactions precisely – for example, lip-licking would be defined as “a mild rhythmic smacking, slight protrusions of the tongue, a relaxed expression accompanied sometimes by a slight upturn of the corners of the mouth” – and then looking for this same expression in other species. A baby human can’t tell you they like the taste like an adult can, but you can see the same expression. A chimpanzee will do the same with a sweet taste. A rat won’t do exactly the same thing, but they do something similar. By carefully observing and coding the facial expressions that accompany nice and nasty tastes, you can tell what an animal is enjoying and what they aren’t.

Pleasure principles

This method is a breakthrough because it gives us another way of looking at how non-human species feel about things. Most animal psychology uses overt actions – things like pressing levers – as measures. So, for example, if you want to see how a reward affects a rat, you put it in a box with a lever and give it food each time it presses the level. Sure enough, the rat will learn to press the lever once it learns that this produces food. Taste reactivity creates an additional measure, allowing us insight into how much the animal enjoys the food, as well as what it makes it want to do.

From this, the neuroscientists have been able to show that wanting and liking are governed by separate circuits in the brain. The liking system is based in the subcortex, that part of our brain that is most similar to other species. Electrical stimulation here, in an area called the nucleus accumbans, is enough to cause pleasure. Sadly, you need brain surgery and implanted electrodes to experience this. But another way you can stimulate this bit of the brain is via the opioid chemical system, which is the brain messenger system directly affected by drugs like heroin. Like brain surgery, this is also NOT recommended.

Wanting happens in nearby, but distinct, circuits. These are more widely spread around the subcortex than the liking circuits, and use a different chemical messenger system, one based around a neurotransmitter called dopamine. Surprisingly, it is this circuit rather than the one for liking which seems to play a primary role in addiction. For addicts a key aspect of their condition is the way in which people, situations and things associated with drug taking become reminders of the drug that are impossible to ignore. Berridge has hypothesised that this is due to a drug’s direct effects on the wanting system. For addicts any reminder of drug taking triggers a neural cascade, which culminates in feelings of desire, but crucially, without needing any actual enjoyment of the drug to occur.

The reason wanting and liking circuits are so near each other is that they normally work closely together, ensuring you want what you like. But in addiction, the theory goes, the circuits can become uncoupled, so that you get extreme wanting without a corresponding increase in pleasure. Matching this, addicts are notable for enjoying the thing they are addicted to less than non-addicts. This is the opposite of most activities, where people who do the most are also the ones who enjoy it the most. (Most activities except another Christmas tradition, watching television, where you see the same pattern as with drug addictions – people who watch the most enjoy it the least).

So now you know what do when you find yourself chomping your way through yet another packet of crisps over the holiday period. Watch your face and see if you are licking your lips. If you are, perhaps your liking circuits are fully engaged and you’ll be happy with what you’ve eaten when you’re finished. If there’s no lip-licking then perhaps your wanting circuits are in control and you need to exercise some self-restraint. Perhaps after the next mouthful, though.

A familiar sight amid the Christmas supermarket shelves is the box of Black Magic chocolates. It’s a classic product that’s been familiar to British shoppers since the 1930s but less well known is the fact that it was entirely designed by psychologists.

A familiar sight amid the Christmas supermarket shelves is the box of Black Magic chocolates. It’s a classic product that’s been familiar to British shoppers since the 1930s but less well known is the fact that it was entirely designed by psychologists.

The chocolates were produced by Rowntree’s who were a pioneer in using empirical psychology to design products (rather than a Freudian approached preferred by American marketers like Edward Bernays).

The idea was to design an assortment of chocolates that would be tailored to be the ideal off-the-shelf romantic gift. This is from an article (pdf) on the history of Rowntree’s marketing:

The National Institute of Industrial Psychology interviewed 7,000 people over six months on their conception of the perfect chocolate assortment. In another survey, 3,000 preferences for hard, soft, and nut centres exactly determined the proportions of chocolate types in the assortment.

Retailers were consulted and their recommendations on margins and price maintenance were followed carefully. Shopkeepers, moreover, supplied information on buying behavior, and it was discovered that most assortments were purchased by men for women and that they were influenced entirely by value rather than fancy boxes. The now familiar, simple black-and-white box was distinctive and chosen from fifty similar designs.

The marketing was then focussed not on the qualities of the product, but on its potential use in developing relationships.

While this is common practice now, it was quite revolutionary at the time, although you can see from the archive of Black Magic adverts that the approach seems painfully clunky from a modern perspective.

The use of psychologists was part of Rowntree’s pioneering use of psychology throughout its whole business, both including product design and human resources and was also one of the most important moments in the launch of professional psychology in the UK – something covered by a 2001 article (pdf) from The Psychologist.

So while Black Magic chocolates now seem just like a common supermarket item, they’re actually an important part of psychology history.

Here’s my BBC Future column from last week. The original is here. The story here isn’t just about politics, although that’s an important example of capture by genetic reductionists. The real moral is about how the things that we measure are built into our brains by evolution: usually they aren’t written in directly, but as emergent outcomes..

There’s growing evidence to suggest that our political views can be inherited. But before we decide to ditch the ballot box for a DNA test, Tom Stafford explains why knowing our genes doesn’t automatically reveal how our minds work.

There are many factors that shape and influence our political views; our upbringing, career, perhaps our friends and partners. But for a few years there’s been growing body of evidence to suggest that there could be a more fundamental factor behind our choices: political views could be influenced by our genes.

The idea that political views have a genetic component is now widely accepted – or at least widely accepted enough to become a field of study with its own name: genopolitics. This began with a pivotal study, which showed that identical twins shared more similar political opinions than fraternal twins. It suggested that political opinion isn’t just influenced by dinner table conversation (which both kinds of twins share), but through parents’ genes (which identical twins have more in common than fraternal twins). The strongest finding from this field is that the position people occupy on a scale from liberal to conservative is heritable. The finding is surprisingly strong, allowing us to use genetic information to predict variations in political opinion on this scale more reliably than we can use genetic information to predict, say, longevity, or alcoholism.

Does this mean we can give up on elections soon, and just have people send in their saliva samples? Not quite, and this highlights a more general issue with regards to seeking genetic roots behind every aspect of our minds and bodies.

Since we first saw the map of the human genome over ten years ago, it might have seemed like we were poised to decode everything about human life. And through military-grade statistics and massive studies of how traits are shared between relatives, biologists are finding more and more genetic markers for our appearance, health and our personalities.

But there’s a problem – there simply isn’t enough information in the human genome to tell us everything. An individual human has only around 20,000 genes, slightly less than wild rice. This means there is about the same amount of information in your DNA as there is in eight tracks on your mp3 player. What forms the rest of your body and behaviour is the result of a complex unfolding of interactions among your genes, the proteins they create, and the environment.

In other words, when we talk about genes predicting political opinion, it doesn’t mean we can find a gene for voting behaviour – nor one for something like dyslexia or any other behaviour, for that matter. Leaving aside the fact that the studies measured “political beliefs” using an extremely simple scale, one that will give people with very different beliefs the same score, let’s focus on what it really means to say that genes can predict scoring on this scale.

Getting emotional

Obviously there isn’t a gene controlling how people answer questions about their political belief. That would be ridiculous, and require us to assume that somewhere, lurking in the genome, was a gene that lay dormant for millions of years until political scientists invented questionnaire studies. Extremely unlikely.

But let’s not stop there. It isn’t really any more plausible to imagine a gene for voting for liberal rather than conservative political candidates. How could such a gene evolve before the invention of democracy? What would it do before voting became a common behaviour?

The limited amount of information in the genome means that it will be rare to talk of “genes for X”, where X is a specific, complex outcome. Yes, some simple traits – like eye colour – are directly controlled by a small number of genes. But most things we’re interested in measuring about everyday life – for instance, political opinions, other personality traits or common health conditions – have no sole genetic cause. The strength of the link between genetics and the liberal-conservative scale suggests that something more fundamental is being influenced by the genes, something that in turn influences political beliefs.

One candidate could be brain systems controlling our emotional responses. For instance, a study showed that American volunteers who started to sweat most when they heard a sudden noise were also more likely to support capital punishment and the Iraq War. This implies that people whose basic emotional responses to threats are more pronounced end up developing a constellation of more right-wing political opinions. Another study, this time in Britain, showed differences in brain structure between liberals and conservatives – with the amygdala, a part of the brain that learns emotional responses, being larger in conservatives. Again, this suggests that differences in political beliefs might arise from differences in emotional processes.

But notice that there isn’t any suggestion that the political opinions are directly controlled by biology. Rather, the political opinions are believed to develop differently in people with different basic biology. Something like the size of a particular brain area is influenced by our genes, but the pathway from our DNA to an apparently simple variation in a brain region is one with many twists, turns and opportunities for other genes and accidents of history to intervene on.

So the idea that genes can have some influence on political views shouldn’t be shocking – it would be weird if there wasn’t some form of genetic influence. But rather than being the end of the story, it just deepens the mystery of how our biology and our ideas interact.

BBC Radio 1Xtra has just broadcast a fantastic programme about the rapper Scorzayzee who disappeared from the UK scene after, as it turned out, experiencing psychosis and being diagnosed with schizophrenia.

BBC Radio 1Xtra has just broadcast a fantastic programme about the rapper Scorzayzee who disappeared from the UK scene after, as it turned out, experiencing psychosis and being diagnosed with schizophrenia.

It’s a brilliant piece that not only tells the story of Scorzayzee but also cheekily tackles mental health in men – something which is rarely addressed in the media.

Virtually every documentary I’ve ever heard on psychosis is serious-voiced and worthy, while this is funny and engaging, with a fantastic sound-track.

One of Scorzayzee’s best known tracks is Great Britain – a brilliant angry push-back of a track that takes on everything from the economy to the Royal Family.

Apparently, Scorzayzee was paranoid when he wrote it but charmingly, in the programme, the BBC include a brief warning before playing it saying words to the effect of ‘please bear in mind that when Scorzayzee compared the Queen to Saddam Hussein, he was suffering the effects of psychosis’.

Thanks BBC.

You’ll be please to hear that Scorzayzee is now doing fine and makes a brilliant storyteller.

Oddly though, the piece is only online for seven days, so catch it while you can.

Recommended.

Link to ‘Scorzayzee and the S-Word’.

A fascinating study has just mapped which brain areas are most popular among scientists and which are most likely to get you published in the highest impact journals.

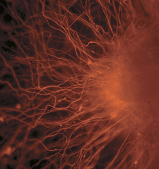

The image below looks like the result of an fMRI scan but instead of showing brain activity from a single experiment, it shows the average brain activity from almost every brain imaging study from 1985 to 2008.

In other words, it shows the popularity of different brain areas as reported in cognitive neuroscience publications.

Actually, if you think about it, this map shows a mix of how often the brain area is active (some areas – like the insula – are active in about a third of imaging experiments so will be more likely to be ‘popular’), how likely the results are to be published, and how motivated scientists are in targeting the area – all of which contribute to their ‘popularity’.

However, the researchers went one stage further and looked at how brain areas are linked to publication in a top tier journal:

…researchers who find activity in a prescribed part of the fusiform gyrus should be confident of having their article selected for publication in a high-impact journal, perhaps due to the role of the region in face processing. Other regions with proposed roles in emotional processing returned similarly stellar performances, including both the ventral and dorsal portions of the rostral medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior insular cortex, the anterior cingulate gyrus, and the amygdala.

The recent interest in reward prediction errors might explain impactful peaks in the mid-brain and ventral striatum, areas that exhibited independent significant effects of impact factor, publication date, and their interaction: studies reporting activation in these regions are published in high-impact journals, and are increasing in number (as a proportion of all studies) over time.

Activity in a contrasting set of regions was negatively predicted by impact factor. Leading the way in ignominy was the secondary somatosensory area, but the supplementary motor area was almost equally disgraced.

The researchers also mapped this onto the brain and although the article is locked, the diagrams are free, and if you look at the second diagram on this page you can see what amounts to a career progression map of the brain.

Studying the red areas are what’ll get you published in the best journals.

So when someone tells you that science is the ‘march of progress’ just remember that it’s actually more like that time when flairs were cool again.

Link to locked study with open diagrams (via @hugospiers)

A while ago I wrote a column in The Psychologist on why psychologists don’t do participant observation research – a type of data gathering where you immerse yourself in the activities of those you want to study.

A while ago I wrote a column in The Psychologist on why psychologists don’t do participant observation research – a type of data gathering where you immerse yourself in the activities of those you want to study.

In response, psychologist James Hartley wrote in and mentioned a remarkable study from 1938 where researchers hid under the beds of students to record their conversations.

The study was published in the Journal of Social Psychology and was titled “Egocentricity in Adult Conversation” and aimed to record natural conversations untainted by researcher-induced self-consciousness.

In order not to introduce artifacts into the conversations, the investigators took special precautions to keep the subjects ignorant of the fact that their remarks were being recorded. To this end they concealed themselves under beds in students’ rooms where tea parties were being held, eavesdropped in dormitory smoking-rooms and dormitory wash-rooms, and listened to telephone conversations.

Remarks were collected in waiting-rooms and hotel lobbies, street-cars, theatres and restaurants. Unwitting subjects were pursued in the streets, in department stores, and in the home. In each case a verbatim record of the remarks was made on the spot. Since the study is concerned with conversations, other sorts of talk, such as games and sales talk, were excluded.

The point of the study was to critique earlier research that had suggested that children tend to engage in lots of ‘ego-related’ self-referencing or self-centred talk which they later grow out of.

The researchers in this study found that college students seem to do so at about an equal level, suggesting that this style of communication may not change as we get older.

The researchers mention they did most of their data collection in a women’s college.

This was presumably in the day where “relax ladies, I’m a scientist” was sufficient to keep you out of jail.

Link to locked 1938 study.

The medical examiner for the Sandy Hook shooting has requested a genetic analysis of killer Adam Lanza. Following this, a powerful editorial in the science magazine Nature has condemned the move suggesting it is “misguided and could lead to dangerous stigmatization.”

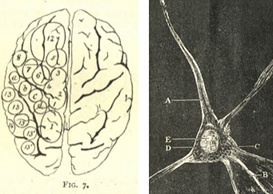

The medical examiner for the Sandy Hook shooting has requested a genetic analysis of killer Adam Lanza. Following this, a powerful editorial in the science magazine Nature has condemned the move suggesting it is “misguided and could lead to dangerous stigmatization.” The images on the right are from the June 1890 edition (the brain) and October 1895 edition (the neuron) and both show some of the then cutting-edge neuroscience that the magazine regularly featured.

The images on the right are from the June 1890 edition (the brain) and October 1895 edition (the neuron) and both show some of the then cutting-edge neuroscience that the magazine regularly featured.

The New Yorker has an amazing

The New Yorker has an amazing

Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist

Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist  The research on the psychological impact of video games tells quite a different story from the stories we get from interest groups and the media. I look at what we know in an

The research on the psychological impact of video games tells quite a different story from the stories we get from interest groups and the media. I look at what we know in an

A familiar sight amid the Christmas supermarket shelves is the box of Black Magic chocolates. It’s a classic product that’s been familiar to British shoppers since the 1930s but less well known is the fact that it was entirely designed by psychologists.

A familiar sight amid the Christmas supermarket shelves is the box of Black Magic chocolates. It’s a classic product that’s been familiar to British shoppers since the 1930s but less well known is the fact that it was entirely designed by psychologists. BBC Radio 1Xtra has just broadcast a fantastic

BBC Radio 1Xtra has just broadcast a fantastic