Cognitive scientists should be explorers of the mind, forging a path through the chaotic world of everyday life before even thinking of retreating to the lab, according to a critical article in the latest edition of the British Journal of Psychology.

Cognitive scientists should be explorers of the mind, forging a path through the chaotic world of everyday life before even thinking of retreating to the lab, according to a critical article in the latest edition of the British Journal of Psychology.

Cognitive science often works like this: researchers notice something interesting in the world, they create a lab-based experiment in an attempt to control everything except what they think is the core mental process, they then test the data to see if it predicts real-world performance.

A new approach, proposed by psychologist Alan Kingstone and colleagues, suggests this is fundamentally wrong-headed and we need to completely rethink how we study the human mind to make it relevant to the real world.

The authors suggest that the standard approach relies on a flawed assumption – that mental processes are like off-the-shelf tools that do the same job, but are just assembled by the mind in different ways depending on the situation.

But imagine if this isn’t the case and mental processes are, in fact, much more fluid and adapt to fit the environment and situation. Not only would we have to change our psychological theories, we would have to change how we study the mind itself because the assumption that we can isolate and test the same mental process in different environments justifies the whole tradition of lab-based research.

The authors suggest an alternative they call ‘cognitive ethology’ and it focuses the efforts of cognitive scientists on a different part of the research process.

Let’s just revisit our potted example of what most cognitive scientists do: they notice something in the world, they create a lab-based experiment, they test to see if it predicts real-world performance.

The first part of this process (noticing -> lab-experiment) is often based on subjective judgements and rough descriptions and isn’t validated until the lab-based experiment is tested.

Kingston and his colleagues argue that scientists should be applying the techniques of science to the first stage – measuring and describing behaviour as it happens in the real world – and only then taking to the lab to see what happens when conditions change.

They give an example of this approach in an interesting driving study:

A Nature publication by Land and Lee (1994) provides a good illustration of a research approach that is grounded in the principle of first examining performance as it naturally occurs. These investigators were interested in understanding where people look when they are steering a car around a corner. This simple issue had obvious implications for human attention and action, as well as for matters as diverse as human performance modelling, vehicle engineering, and road design.

To study this issue, Land and Lee monitored eye, head, steering wheel position, and car speed, as drivers navigated a particularly tortuous section of road. Their study revealed the new and important finding that drivers rely on a ‘tangent point’ on the inside of each curve, seeking out this point 1–2 seconds before each bend and returning to it reliably.

Later, other researchers used a lab-based driving simulator study to systematically alter how much of this ‘tangent point’ was available to see what caused abnormal driving.

The authors also make the point that this approach is much better at helping us understand why something happens the way it does, because it ties it to the real world and helps us integrate it with the our knowledge of personal meaning.

It’s an interesting approach and meshes nicely with a recent article on cultural cognitive neuroscience in Nature Reviews Neuroscience. It looked at a number of fascinating studies on cultural influences on mind and brain function and discusses how we can go about understanding the interaction between culture and the brain.

If you want to skip the theoretical parts, Box 1 is worth looking at just for a brief summary of some intriguing cultural differences in the way we think.

The piece was also rather expertly covered by Neuroanthropology who cover the main punchlines and discuss some of the claims.

Link to ‘cognitive ethology’ article.

Link to PubMed entry for ‘cognitive ethology’ article.

Link to ‘cultural neuroscience’ article.

Link to PubMed entry for ‘cultural neuroscience’ article.

My new favourite typo: if you’re fed up with the sound of electric rock n’ roll perhaps you’d prefer some autistic guitar.

My new favourite typo: if you’re fed up with the sound of electric rock n’ roll perhaps you’d prefer some autistic guitar. The BPS Research Digest has

The BPS Research Digest has  Psychologist Petra Boyton has written a fantastic

Psychologist Petra Boyton has written a fantastic  I just found this fascinating

I just found this fascinating  Not Exactly Rocket Science has a great <a href="

Not Exactly Rocket Science has a great <a href=" Today’s BPS Research Digest has a wonderfully ironic and recursive Freudian slip in a

Today’s BPS Research Digest has a wonderfully ironic and recursive Freudian slip in a  The Atlantic has a provocative

The Atlantic has a provocative  The August edition of the Nature Neuroscience podcast, NeuroPod,

The August edition of the Nature Neuroscience podcast, NeuroPod,  The

The

The Boston Globe has an interesting

The Boston Globe has an interesting

Cognitive scientists should be explorers of the mind, forging a path through the chaotic world of everyday life before even thinking of retreating to the lab, according to a critical

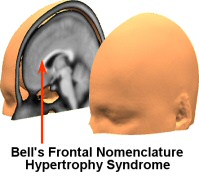

Cognitive scientists should be explorers of the mind, forging a path through the chaotic world of everyday life before even thinking of retreating to the lab, according to a critical  I have discovered shocking evidence that computers are affecting the brain. After extensive research, I have discovered the problem is remarkably specific and I have isolated it to an individual brain area affected by one particular application. Microsoft Word is causing abnormal growth in the frontal lobes.

I have discovered shocking evidence that computers are affecting the brain. After extensive research, I have discovered the problem is remarkably specific and I have isolated it to an individual brain area affected by one particular application. Microsoft Word is causing abnormal growth in the frontal lobes. The September issue of The Psychologist has two excellent and freely available articles that smash the popular myths of scientific psychology.

The September issue of The Psychologist has two excellent and freely available articles that smash the popular myths of scientific psychology.