Ketamine is both a powerful hallucinogenic drug and an effective anaesthetic that can create striking out-of-body experiences.

Ketamine is both a powerful hallucinogenic drug and an effective anaesthetic that can create striking out-of-body experiences.

The history of ‘Taming the Ketamine Tiger’ is recounted by the doctor who has been most involved in researching and understanding the curious compound in an open-access article published in Anesthesiology.

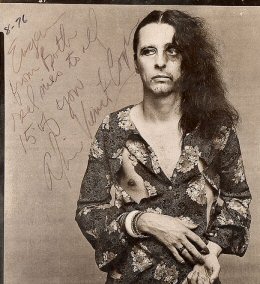

The author is the wonderfully named Edward Domino who was one of the first people to study both the pain killing and mind bending effects of ketamine.

His article recounts the history of the compound from its discovery, to its use in surgery, to its deployment in the Vietnam war and its championing by the consciousness exploring counter-culture.

The paper is written for fellow pharmacologists and so has some fairly technical parts (the section ‘Ketamine Pharmacology’ is probably best skipped if you’re not into the gritty details of how it affects the body and brain) but also has some wonderful personal recollections and anecdotes from the drug’s history.

About 1978, the prominent physician, researcher, and mystic John C. Lilly, M.D. (1915–2001), self-administered ketamine to induce an altered state of consciousness. He summarized his many unique experiences as “a peeping Tom at the keyhole of eternity.” These included sensory deprivation while submerged in a water tank, communication with dolphins, and seduction by repeated ketamine use.

In 1978, Moore and Alltounian reported on their personal ketamine use. Marcia Moore was a celebrated yoga teacher, Howard Alltounian, M.D., a respected clinical anesthesiologist. They reportedly got high on ketamine together and after two ketamine “trips” fell in love and became engaged after 1 week. They felt they were “pioneering a new path to consciousness.” Ms. Moore was called the priestess of the Goddess Ketamine. She took the drug daily and apparently developed tolerance.

For her, ketamine was a seductress, not a goddess. Her husband warned her of its dangers. She slept only a few hours each night. She agreed that she was wrong about a lot of things and was “going to stay with it until it is tamed.” However, Moore was unable to tame the ketamine tiger and in January 1979 disappeared. The assumption was that she injected herself with ketamine and froze to death in a forest.

You can read the full article here although it’s not clear to me that the link is stable enough to be archived, in which case the DOI entry points here although you may need to do some clicking through to find the full text.

Anyway, a fascinating look back at a complex compound from the man at the centre of its science.

Link to ‘Taming the Ketamine Tiger’ in Anesthesiology.

Link to DOI entry for same.

Neurotribes has a fantastic

Neurotribes has a fantastic  The remains of

The remains of

BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time has a wonderful programme on the history of our knowledge about the nervous system which you can listen to streamed from the

BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time has a wonderful programme on the history of our knowledge about the nervous system which you can listen to streamed from the

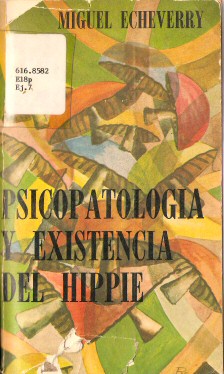

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion.

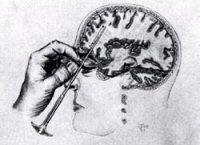

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion. The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication. History of Psychology has just published a brief

History of Psychology has just published a brief  You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed.

You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed. The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated.

The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated. Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents.

Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents. The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”.

The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”. The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.

The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution. Pioneering neurosurgeon

Pioneering neurosurgeon

I recently indulged in the outrageous luxury of placing an international order for the

I recently indulged in the outrageous luxury of placing an international order for the