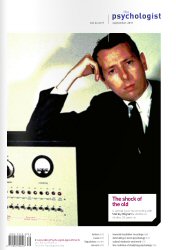

For a short time, the scientific community was excited about the smell of schizophrenia.

For a short time, the scientific community was excited about the smell of schizophrenia.

In 1960, a curious article appeared in the Archives of General Psychiatry suggesting not only that people with schizophrenia had a distinctive smell, but that the odour could be experimentally verified.

The paper by psychiatrists Kathleen Smith and Jacob Sines noted that “Many have commented upon the strange odour that pervades the back wards of mental hospitals” and went on to recount numerous anecdotes of the supposedly curious scent associated with the diagnosis.

Having worked on a fair few ‘back wards of mental hospitals’ in my time, my first reaction would be to point out that the ‘strange odour’ is more likely to be the staff than the patients but Smith and Sines were clearly committed to their observations.

They collected the sweat from 14 white male patients with schizophrenia and 14 comparable patients with ‘organic brain syndromes’ and found they could train rats to reliably distinguish the odours while a human panel of sweat sniffers seemed to be able to do the same.

Seemingly backed up by the nasal ninja skills of two different species, science attempted to determine the source of the ‘schizophrenic odour’.

Two years later researchers from Washington suggested the smell might be triggered by the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa but an investigation found it was no more common in people with schizophrenia than those without the diagnosis.

But just before the end of the 60s, the original research team dropped a scientific bombshell. They claimed to have identified the schizophrenia specific scent and got their results published in glittery headline journal Science.

Using gas chromotography they identified the ‘odorous substance’ as trans-3-methyl-2-hexenoic acid, now known as TMHA.

At this point, you may be staring blankly at the screen, batting your eyelids in disinterest at the mention of a seemingly minor chemical associated with the mental illness, but to understand why it got splashed across the scientific equivalent of Vogue magazine you need to understand something about the history, hopes and dreams of psychiatry research.

For a great part of the early 20th century, psychiatry was on the hunt for what was called an ‘endogenous schizotoxin’ – a theorised internal toxin that supposedly triggered the disorder.

A great part of the early scientific interest in psychedelics drew on the same idea as psychiatrists wondered whether reality-bending drugs like LSD and mescaline were affecting the same chemicals, or, in some cases, might actually be the ‘schizotoxins’ themselves.

So a chemical uniquely identified in the sweat of people with schizophrenia was big news. Dreams of Nobel Prizes undoubtedly flashed through the minds of the investigators as they briefly allowed themselves to think about the possibility of finally cracking the ‘mystery of madness’.

As the wave of excitement hit, other scientists quickly hit the labs but just couldn’t confirm the link – the results kept coming in negative. In 1973 the original research team added their own study to the disappointment and concluded that the ‘schizophrenic odour’ was dead.

Looking back, we now know that TMHA is genuinely an important component in sweat odour. Curiously, it turns out it is largely restricted to Caucasian populations but no link to mental illness or psychiatric disorder has ever been confirmed.

The theory seems like an curious anomaly in the history of psychiatry but it occasionally makes a reappearance. In 2005 a study claimed that the odour exists but is “complex and cannot be limited to a single compound, but rather to a global variation of the body odor” but no replications or further investigations followed.

I, on the other hand, am still convinced it was the staff that were the source of the ‘strange odour’, but have yet to get research funding to confirm my pioneering theories.

Now available in Italian L’odore della schizofrenia

(thanks Giuliana!)

A fascinating but unfortunately locked review article on the psychology of vegetarianism has this paragraph on how avoiding the pleasures of cooked flesh has been seen as a mental illness in times past.

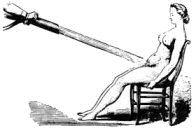

A fascinating but unfortunately locked review article on the psychology of vegetarianism has this paragraph on how avoiding the pleasures of cooked flesh has been seen as a mental illness in times past. We’ve covered The Technology of Orgasm

We’ve covered The Technology of Orgasm  Scientific American’s Bering in Mind has a fantastic

Scientific American’s Bering in Mind has a fantastic

Monitor on Psychology has a fascinating

Monitor on Psychology has a fascinating  From a curious

From a curious

Neurology has an

Neurology has an  A brief

A brief

I’ve just found this fascinating discussion on the psychopharmacology of ‘witches ointments’, that supposedly allowed 16th century witches to ‘fly’.

I’ve just found this fascinating discussion on the psychopharmacology of ‘witches ointments’, that supposedly allowed 16th century witches to ‘fly’.