In 1992, the BBC broadcast Ghostwatch, one of the most controversial shows in television history and one that has had a curious and unexpected effect on the course of psychiatry.

In 1992, the BBC broadcast Ghostwatch, one of the most controversial shows in television history and one that has had a curious and unexpected effect on the course of psychiatry.

The programme was introduced as a live report into a haunted house but in reality, it was fiction. This is now a common plot device, but the broadcast happened in 1992, years before even The Blair Witch Project used the documentary format to tell a fictional story and viewers were used to news-like programmes presenting news-like facts.

But despite some subtle nods to its fictional nature, the fact it was broadcast on Halloween and the ridiculous conclusion (the poltergeist eventually escapes from the house, takes control of the BBC and possesses presenter Michael Parkinson), many people believed the ‘documentary’ was real and that the programme was capturing these astounding events as they happened. You can watch it on YouTube and see how it was introduced.

Consequently, lots of people were genuinely frightened by the programme, including many children who were watching with their families. As a result, the BBC was flooded with calls and letters and were forced to start an investigation into the programme.

As the controversy raged on, an article appeared in the British Medical Journal, written by two doctors from Gulson Hospital in Coventry, reporting post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in two children that was apparently caused by watching Ghostwatch.

Case 1

This boy had been frightened by Ghostwatch and had refused to watch the ending. He subsequently expressed fear of ghosts, witches, and the dark, constantly talking about them and seeking reassurance. He suffered panic attacks, refused to go upstairs alone, and slept with the bedroom light on. He had nightmares and daytime flashbacks and banged his head to remove thoughts of ghosts. He became increasingly clingy and was reluctant to go to school or to allow his mother to go out without him.

Although not without scepticism, several other cases were published as replies to these initial reports producing a small case series of PTSD caused by the TV show.

These minor cases drifted into the history of medicine until people started to debate what event should be considered a sufficiently traumatic event in order to diagnose PTSD.

At the moment, the current DSM-IV-TR diagnosis for PTSD says that “the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” and that the person’s response involved “intense fear, helplessness, or horror”.

It’s the “confronted with” part that allows people who have seen distressing things on TV and reacted with “intense fear, helplessness, or horror” to be diagnosed with PTSD.

At the time Ghostwatch was broadcast the criteria required that “the person has experienced an event that is outside the range usual human experience and that would be markedly distressing to almost anyone” which could similarly be interpreted to allow TV programmes to cause the disorder.

The new proposed criteria for the DSM-5 wouldn’t allow television-triggered PTSD. In fact it specifically says that exposure to traumatic events “does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures, unless this exposure is work related.”

Ghostwatch has played a part in changing how PTSD will be diagnosed. Although a major motivation was the wave of PTSD diagnoses after watching coverage of 9/11 on TV, the fictional ghost investigation is often cited in the medical literature as an example of how the existing criteria can lead to absurd consequences.

Although the programme is more famous for its effect on the history of media, it remains a minor but significant spectre in psychiatry’s past.

Link to GhostWatch entry on Wikipedia.

BBC Radio 4’s brilliant psychology series Mind Changers has made a comeback and has a new season looking at some of the biggest ideas in cognitive science.

BBC Radio 4’s brilliant psychology series Mind Changers has made a comeback and has a new season looking at some of the biggest ideas in cognitive science. In 1992, the BBC broadcast

In 1992, the BBC broadcast

A fascinating

A fascinating  Nature has just published a fantastic Alan Turing

Nature has just published a fantastic Alan Turing  The Rolling Stones launched their career in a social therapeutic club, designed to help troubled youth with communication skills. The club became legendary in rock ‘n roll history but its therapeutic roots have almost been forgotten.

The Rolling Stones launched their career in a social therapeutic club, designed to help troubled youth with communication skills. The club became legendary in rock ‘n roll history but its therapeutic roots have almost been forgotten.

A new

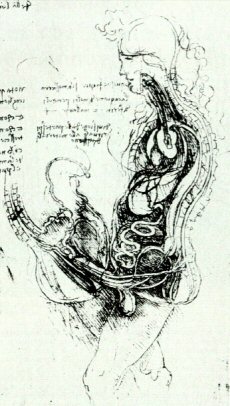

A new  In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain.

In Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, the penis is connected directly to the brain. ‘Space madness’ was a serious concern for psychiatrists involved in the early space programme. A new

‘Space madness’ was a serious concern for psychiatrists involved in the early space programme. A new  A

A

A new

A new