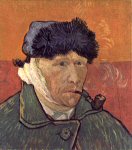

I just found this fascinating account of how Vincent Van Gogh cut off his own ear while seemingly severely mentally ill, the event that led him to paint one of his most famous pictures.

I just found this fascinating account of how Vincent Van Gogh cut off his own ear while seemingly severely mentally ill, the event that led him to paint one of his most famous pictures.

The account is apparently reconstructed from known events at the time but also has van Gogh’s own description of the event, taken from letters to his sister.

On Christmas Eve 1888, after Gauguin already had announced he would leave, van Gogh suddenly threw a glass of absinthe in Gauguin’s face, then was brought home and put to bed by his companion. A bizarre sequence of events ensued. When Gauguin left their house, van Gogh followed and approached him with an open razor, was repelled, went home, and cut off part of his left earlobe, which he then presented to Rachel, his favorite prostitute.

The police were alerted; he was found unconscious at his home and was hospitalized. There he lapsed into an acute psychotic state with agitation, hallucinations, and delusions that required 3 days of solitary confinement. He retained no memory of his attacks on Gauguin, the self-mutilation, or the early part of his stay at the hospital…

At the hospital, Felix Rey, the young physician attending van Gogh, diagnosed epilepsy and prescribed potassium bromide. Within days, van Gogh recovered from the psychotic state. About 3 weeks after admission, he was able to paint Self-Portrait With Bandaged Ear and Pipe, which shows him in serene composure. At the time of recovery and during the following weeks, he described his own mental state in letters to Theo and his sister Wilhelmina: “The intolerable hallucinations have ceased, in fact have diminished to a simple nightmare, as a result of taking potassium bromide, I believe.”

“I am rather well just now, except for a certain undercurrent of vague sadness difficult to explain.” “While I am absolutely calm at the present moment, I may easily relapse into a state of overexcitement on account of fresh mental emotion.” He also noted “three fainting fits without any plausible reason, and without retaining the slightest remembrance of what I felt”

Although absinthe is commonly associated with hallucinations and madness, and the author of the article wonders whether it might have helped cause his epilepsy, this is unlikely due to the fact that the effect of absinthe’s ‘special ingredient’ is largely a myth.

The distinctive aspect of the drink, the chemical thujone from the wordwood plant, is actually present in such small quantities that absinthe has virtually no psychoactive effects beyond the alcohol.

However, epilepsy does raise the risk of psychosis and it is suspected that he had temporal lobe epilepsy which is particularly associated with this reality-bending mental state.

Link to AJP article on ‘The Illness of Vincent van Gogh’.

Slate has a brilliant

Slate has a brilliant  A curious anecdote about legendary neurologist

A curious anecdote about legendary neurologist

The Independent has an excellent

The Independent has an excellent

The Providentia blog has a brilliant

The Providentia blog has a brilliant

The New Yorker has a fantastic

The New Yorker has a fantastic

A remarkably accurate account of the

A remarkably accurate account of the  New York Magazine has an in-depth

New York Magazine has an in-depth  Pioneering neurosurgeon

Pioneering neurosurgeon