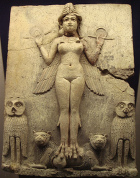

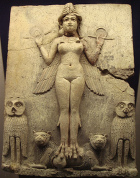

Despite the news reports, researchers probably haven’t discovered a mention of ‘PTSD’ from 1300BC Mesopotamia. The claim is likely due to a rather rough interpretation of Ancient Babylonian texts but it also reflects a curious interest in trying to find modern psychiatric diagnoses in the past, which tells us more about our own clinical insecurities than the psychology of the ancient world.

Despite the news reports, researchers probably haven’t discovered a mention of ‘PTSD’ from 1300BC Mesopotamia. The claim is likely due to a rather rough interpretation of Ancient Babylonian texts but it also reflects a curious interest in trying to find modern psychiatric diagnoses in the past, which tells us more about our own clinical insecurities than the psychology of the ancient world.

The claim comes from a new article published in Early Science and Medicine and it turns out there’s a pdf of the article available online if you want to read it in full.

The authors cite some passages from Babylonian medical texts in support of the fact that ‘symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder’ were recorded in soldiers. Here are the key translated passages from the article:

14.34 “If his words are unintelligible for three days […] his mouth [F…] and he experiences wandering about for three days in a row F…1.”

14.35 “He experiences wandering about (for three) consecutive (days)”; this means: “he experiences alteration of mentation (for three) consecutive (days).”

14.36 “If his words are unintelligible and depression keeps falling on him at regular intervals (and he has been sick) for three days F…]”

19.32 “If in the evening, he sees either a living person or a dead person or someone known to him or someone not known to him or anybody or anything and becomes afraid; he turns around but, like one who has [been hexed with?] rancid oil, his mouth is seized so that he is unable to cry out to one who sleeps next to him, ‘hand’ of ghost (var. hand of […]).”

19.33 “[If] his mentation is altered so that he is not in full possession of his faculties, ‘hand’ of a roving ghost; he will die.”

19.34 “If his mentation is altered, […] (and) forgetfulness(?) (and) his words hinder each other in his mouth, a roaming ghost afflicts him. (If) […], he will get well.”

Firstly, it’s clearly a huge stretch to suggest these are symptoms of PTSD which is defined as groupings of intrusive memories of the traumatising event, heightened arousal or emotional numbing, avoidance of reminders and, since the DSM-5, depression-like symptoms.

The authors suggest that the strongest evidence for the fact that the ancient descriptions are PTSD is that the ‘ghost’ mentioned in the text is often considered to be the ghosts of enemies whom the patient killed during military operations, and these could be PTSD-like flashbacks.

The trouble is that ‘ghosts’ are given as causes of many disorders in Babylonian medicine. Furthermore, all of the symptoms the authors describe could clearly also describe epilepsy and, in fact, are described in Babylonian texts on epilepsy.

For example, these are all symptoms described in BM 47753 a Babylonian tablet on epilepsy, discussed a 1990 article, that also describes wandering, confusion and unintelligible speech.

If he keeps going into and out of (his house) or getting into and out of his clothes .. or talks unintelligibly a great deal, does not any more eat his bread and beer rations and does not go to bed…

If, in a state of fear, he keeps getting up and sitting down, (or) if he mutters unintelligibly a great deal and becomes more and more restless…

Most symptoms are diagnosed as a form of being touched by the hand of a supernatural being. Below are some ‘ghost’ afflictions that are clearly epilepsy related, including ‘ghosts’ who have died violently in various ways, including a ‘mass killing’.

If at the end of his fit his limbs become paralysed, he is dazed (or, dizzy), his abdomen is “wasted” (sc., as of one in need of food) and he returns everything which is put into his mouth …….-hand of a ghost who has died in a mass killing.

If when his limbs become at rest again like those of a healthy person his mouth is seized so that he cannot speak,-hand of the ghost of a murderer. R: hand of the ghost of a person burned to death in a fire.

If when his limbs become at rest again like those of a healthy person he remains silent and does not eat anything,-hand of the ghost of a murderer; alternatively, hand of the ghost of a person burned to death in a fire

Oddly, the authors of the ‘ancient PTSD’ article suggest that references to slurring of speech and cognitive difficulties might reflect co-morbid drug abuse. They also admit that all their cited symptoms could be caused by head injury but as prognosis is given as non-fatal, they were probably PTSD-related. But again, epilepsy seems a much better fit here both from a contemporary and Babylonian perspective.

In fact, historians Kinnier Wilson and Reynolds, who wrote the 1990 article on Babylonian epilepsy texts, were quite convinced that references to ‘ghosts’ were ancient terms for nocturnal epilepsy, not ‘flashbacks’.

But it’s also worth mentioning that the ‘ancient PTSD’ argument is in a long-line of studies that attempt to match contemporary psychiatric diagnoses to vague historical references as a way of legitimising the modern concepts.

However, the ways in which psychological distress, particularly trauma, is expressed are massively affected by culture. PTSD is unlikely to be a concept that transcends time, place and social structure.

In fact, historians have not been able to convincingly find any PTSD-like descriptions in history and there seems a virtually complete absence of any records of flashbacks in the medical records of First and Second World War veterans, let alone in Ancient Babylon.

War, violence and tragedy has left its psychological mark on individuals from the beginning of time.

PTSD is a useful diagnosis we’ve created to help us deal with some of the consequences of these awful events in the limited but important contexts in which it occurs – but it’s not a universal feature of human nature.

Who knows whether anything like PTSD existed for the Babylonians but the fact that we can use it to help people is all we need to legitimise it.

The Neurologist has a fascinating case report of a women with Parkinson’s disease who experienced a fluctuating belief that she didn’t exist.

The Neurologist has a fascinating case report of a women with Parkinson’s disease who experienced a fluctuating belief that she didn’t exist. The last time I almost went blind staring at “that dress” was thanks to Liz Hurley and on this occasion I find myself equally unsatisfied.

The last time I almost went blind staring at “that dress” was thanks to Liz Hurley and on this occasion I find myself equally unsatisfied.

In a moving and defiant

In a moving and defiant

The British

The British

Despite the

Despite the

Articles on people’s experience of the altered states of madness often fall into similar types: tragedy, revelation or redemption. Very few do what a wonderful

Articles on people’s experience of the altered states of madness often fall into similar types: tragedy, revelation or redemption. Very few do what a wonderful