History of Psychology has just published a brief article I wrote about my trip to Hospital San Lázaro in Quito, Ecuador, one of the oldest psychiatric hospitals in Latin America and still a working mental health facility.

History of Psychology has just published a brief article I wrote about my trip to Hospital San Lázaro in Quito, Ecuador, one of the oldest psychiatric hospitals in Latin America and still a working mental health facility.

…

In the strong morning light, the whitewashed walls of the Hospital Psiquiátrico San Lázaro come alive with lucid sunshine. The beautiful but commanding building looks out over Quito’s old town, set back from the historic centre, where it retains its ambivalent mixture of the modern and medieval. It’s not a welcoming structure and, externally, seems more castle than care facility. Visitors need to enter large metal gates, before climbing an external ramp, and then must announce themselves to reception in the imposing stone gatehouse. I had come, I explained, to visit the hospital, but so far had no luck getting in touch with anyone to organise an appointment.

I had heard of ‘El Hospicio de Quito’ from colleagues in Colombia who had informed me that it was one of the oldest psychiatric hospitals in Latin America, but yet it merits barely a mention in the English language literature and surprisingly little in the Spanish. Determined to discover more, I visited the hospital and, after arranging to return with a letter officially requesting my visit, I was shown round by one of the staff psychologists.

You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed.

You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed.

The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated.

The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated.

As I discovered at the time, the hospital itself is not the best place to go to research its history and I have learnt in retrospect that there are much better sources for the serious investigator – albeit ones which necessitate a visit to the city. Nevertheless, I managed to find some background in Luciano Andrade Marín’s (2003) La Lagartija que Abrió la Calle Mejía; Historietas de Quito thanks to the assistance of the staff at the Biblioteca Municipal. The hospital lies on the site of a Jesuit seminary originally founded in 1587 as a place of training and spiritual retreat.

Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents.

Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents.

The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”.

The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”.

Sadly, I found out little about the 20th Century history of the institution, but now considerably more humane and caring, the institution is one of the most important psychiatric hospital in Ecuador. Those wishing to investigate further may want to obtain Mariana Landázuri Camacho’s (2008) book Salir del encierro. Medio siglo del Hospital Psiquiátrico San Lázaro, which apparently contains a more complete history, although seems only available from select shops in Quito. The city libraries I visited could only provided limited help but apparently archives relating to the hospital are held in Quito’s Museo Nacional de Medicina.

The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.

The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.

Link to article entry at History of Psychology.

I’ve just discovered a engrossing two-part BBC World Service documentary on ‘oral history’ and how the process of getting everyday folk to relay their memories of important event often challenges the authorised memories of official history.

I’ve just discovered a engrossing two-part BBC World Service documentary on ‘oral history’ and how the process of getting everyday folk to relay their memories of important event often challenges the authorised memories of official history. In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion.

In 1972, Colombian psychiatrist Miguel Echeverry published a book arguing that hippies were not a youth subculture but the expression of a distinct mental illness that should be treated aggressively lest it spread through the population like a contagion. The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

The image on the right is from one of the adverts in the book, all of which advertise the drug Lucidril as a ‘treatment’ for hippies, and it’s no surprise that the book was sponsored by the makers of the medication.

Being in coma could play havoc with your nail care routine.

Being in coma could play havoc with your nail care routine.

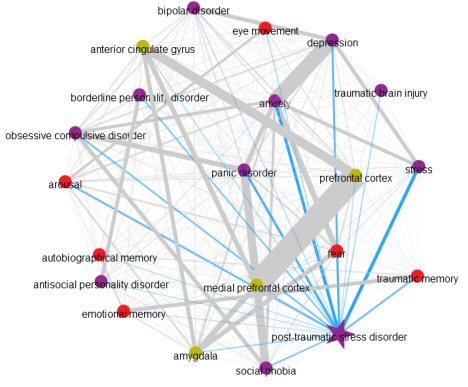

The brilliant Neuroskeptic has created a

The brilliant Neuroskeptic has created a

Cannibalism is a lot more common in human history than you’d guess and an intriguing

Cannibalism is a lot more common in human history than you’d guess and an intriguing  Ecstasy users often describe the high as feeling ‘loved up’ and

Ecstasy users often describe the high as feeling ‘loved up’ and

History of Psychology has just published a brief

History of Psychology has just published a brief  You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed.

You can see virtually nothing of the hospital from the gatehouse, but after stepping through the iron doors you find yourself in a courtyard of surprisingly gentle beauty, filled with trees and fountains, and surrounded on all sides by the building’s open internal arches. Although built at the dawn of the Renaissance, the hospital feels more like a medieval fantasy and is made up of a collection of multi-level walkways and clinical areas in cobbled courtyards that seem to have been ‘added on’ rather than designed. The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated.

The consulting rooms are sparse with high ceilings, while the patient wards, both male and female, consist of large dormitories and both indoor and outdoor communal areas around which patients meander until therapy, mealtime or visits take priority. But despite the antique façade there was determined modernisation programme in progress, with both the historic chapel being restored and the clinical facilities being renovated. Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents.

Although damaged in the volcano eruption of 1698 and the earthquake of 1755, the building retains many of its Jesuit features including an impressive baroque entrance arch. The building lay empty for some years after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 although by 1785 the Royal Order of Spain (a plaque in the hospital names them the Mercedarians) had converted the seminary into a hospice for the poor, disabled, mad and leprous. By the time of Ecuador’s independence, the hospice was notorious for the brutal treatment handed out to its mentally disturbed residents. The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”.

The hospice was taken over by The Sisters of Charity in 1870 who dedicated the institution to the mentally ill and began altering the building to better accommodate its more singular purpose. Patient care was not so forward thinking, however, and a doctor who visited the hospital in 1903, quoted in Andrade Marín (2003), minced no words in describing the conditions: the patients “were treated like animals… writhing in unclean yards, enclosed in dirt and gloomy dungeons, fed like wild beasts… naked and maltreated”. The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.

The building is not open to the public, but the staff were friendly and welcoming, and, at the very least, the exterior is worth a visit for its architectural beauty and evocative location. There are no histories of this important institution in the English academic literature, and Landázuri Camacho’s book is apparently the only serious attempt at historical scholarship anywhere. Clearly, there is still much to be investigated about the history of this important institution.