We are born immortal, as far as we know at the time, and slowly we learn that we are going to die. For most children, death is not fully understood until after the first decade of life – a remarkable amount of time to comprehend the most basic truth of our existence.

We are born immortal, as far as we know at the time, and slowly we learn that we are going to die. For most children, death is not fully understood until after the first decade of life – a remarkable amount of time to comprehend the most basic truth of our existence.

There are poetic ways of making sense of this difficulty: perhaps an understanding of our limited time on Earth is too difficult for the fragile infant mind to handle, maybe it’s evolution’s way of instilling us with hope; but these seductive theories tend to forget that death is more complex than we often assume.

To completely understand the significance of death, researchers – mortality psychologists if you will – have identified four primary concepts we need to grasp: universality (all living things die), irreversibility (once dead, dead forever), nonfunctionality (all functions of the body stop) and causality (what causes death).

In a recent review of studies on children’s understanding of death, medics Alan Bates and Julia Kearney describe how:

Partial understanding of universality, irreversibility, and nonfunctionality usually develops between the ages of 5 and 7 years, but a more complete understanding of death concepts, including causality, is not generally seen until around age 10. Prior to understanding nonfunctionality, children may have concrete questions such as how a dead person is going to breathe underground. Less frequently studied is the concept of personal mortality, which most children have some under standing of by age 6 with more complete understanding around age 8–11.

But this is a general guide, rather than a life plan. We know that children vary a great deal in their understanding of death and they tend to acquire these concepts at different times.

Although interesting from a developmental perspective these studies also have clear, practical implications.

Most children will know someone who dies and helping children deal with these situations often involves explaining death and dying in a way they can understand while addressing any frightening misconceptions they might have. No, your grandparent hasn’t abandoned you. Don’t worry, they won’t get lonely.

But there is a starker situation which brings the emerging ability to understand mortality into very sharp relief. Children who are themselves dying.

The understanding of death by terminally ill children has been studied by a small but dedicated research community, largely motivated by the needs of child cancer services.

One of the most remarkable studies, and perhaps, one of the most remarkable studies in the whole of palliative care, was completed by the anthropologist Myra Bluebond-Langner and was published as the book The Private Worlds of Dying Children.

Bluebond-Langner spent the mid 1970’s in an American child cancer ward and began to look at what the children knew about their own terminal prognosis, how this knowledge affected social interactions, and how social interactions were conducted to manage public awareness of this knowledge.

Her findings were nothing short of stunning: although adults, parents, and medical professionals, regularly talked in a way to deliberately obscure knowledge of the child’s forthcoming death, children often knew they were dying. But despite knowing they were dying, children often talked in a way to avoid revealing their awareness of this fact to the adults around them.

Bluebond-Langner describes how this mutual pretence allowed everyone to support each other through their typical roles and interactions despite knowing that they were redundant. Adults could ask children what they wanted for Christmas, knowing that they would never see it. Children could discuss what they wanted to be when they grew up, knowing that they would never get the chance. Those same conversations, through which compassion flows in everyday life, could continue.

This form of emotional support was built on fragile foundations, however, as it depended on actively ignoring the inevitable. When cracks sometimes appeared during social situations they had to be quickly and painfully papered over.

When children’s hospices first began to appear, one of their innovations was to provide a space where emotional support did not depend on mutual pretence.

Instead, dying can be discussed with children, alongside their families, in a way that makes sense to them. Studying what children understand about death is a way of helping this take place. It is knowledge in the service of compassion.

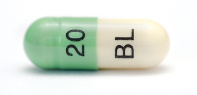

I’ve got an article in today’s Observer about the disastrous Psychoactive Substances Bill, a proposed law designed to outlaw all psychoactive substances based on a fantasy land version of neuroscience.

I’ve got an article in today’s Observer about the disastrous Psychoactive Substances Bill, a proposed law designed to outlaw all psychoactive substances based on a fantasy land version of neuroscience.

There’s much debate in the media about a culture of demanding ‘safe spaces’ at university campuses in the US, a culture which has been accused of restricting free speech by defining contrary opinions as harmful.

There’s much debate in the media about a culture of demanding ‘safe spaces’ at university campuses in the US, a culture which has been accused of restricting free speech by defining contrary opinions as harmful. MIT Technology Review has jaw dropping article

MIT Technology Review has jaw dropping article  I had always thought that suicide was made illegal in medieval times due to religious disapproval until suicidal people were finally freed from the risk of prosecution by the 1961 Suicide Act.

I had always thought that suicide was made illegal in medieval times due to religious disapproval until suicidal people were finally freed from the risk of prosecution by the 1961 Suicide Act.

The Lancet Psychiatry has a fantastic

The Lancet Psychiatry has a fantastic