The Guardian are reporting that the London Metropolitan Police have deployed ‘super recogniser’ officers to Notting Hill Carnival to pick out known criminals from the crowd.

The Guardian are reporting that the London Metropolitan Police have deployed ‘super recogniser’ officers to Notting Hill Carnival to pick out known criminals from the crowd.

This is curious because this is a verified ability that has only recently been reported in the scientific literature.

It has been long known that some people have severe difficulties recognising faces – something called prosopagnosia and sometimes inaccurately labelled ‘face blindness’.

But more recently, it was discovered that a tiny minority of people are ‘super recognisers’ – with exceptional face recognition abilities – meaning they can pick out a previously identified face from huge numbers of possibilities.

A more recent fMRI study found that super recognisers tend to show a greater level of activity in the fusiform gyrus.

This area is heavily associated with face recognition, although debates are ongoing whether it is face-dedicated or just specialised for learned fine-grained visual recognition of various sorts.

It’s not clear how the Met Police identified their ‘super recogniser’ officers but it seems it might be an interesting exercise in screening for key neuropsychological characteristics and deploying those officers to the appropriate task.

Needless to say, picking out a few dodgy faces from a street party that welcomes a million people every year would be exactly this sort of job.

More details from the The Guardian report:

…17 specialist officers will be holed up in a central control room several miles away in Earls Court monitoring live footage in an attempt to identify known offenders.

Chief superintendent Mick Johnson from the Metropolitan police said it was the first time the “recognisers” – who have been selected for their ability to remember hundreds of offenders’ faces – have been used to monitor a live event.

“This type of proactive operation is the first one we have done in earnest in real time so we are going to be looking at it very closely to see how effective it is and what we get out of it,” he said.

The Met has 180 so-called super recognisers – most of whom came to the fore in the aftermath of the London riots when they managed to identify more than a quarter of the suspects who were caught on CCTV footage…

One of the super recognisers on duty will be Patrick O’Riordan, who says he has had an ability to pick people out in a crowd and recall faces since he joined the Met 11 years ago.

“It is with me all the time. Often when I am on a day off or out with my girlfriend I will see someone and know straight away who they are and where they fit in,” said 45-year-old. “It could be their eyes or the shape of their forehead or their gait, but something usually sticks with me. It something that started from day one as a police officer – really it is just something that I took too naturally.”

Link to Guardian article on super recogniser officers at the Carnival.

Link to summary of study that identified ‘super recognisers’.

pdf of full-text of the same paper.

Regular readers will know of my ongoing fascination with the fate of the old psychiatric asylums and how they’re often turned into luxury apartments with not a whisper of their previous life.

Regular readers will know of my ongoing fascination with the fate of the old psychiatric asylums and how they’re often turned into luxury apartments with not a whisper of their previous life. Aeon Magazine has an amazing

Aeon Magazine has an amazing

The New York Times has an

The New York Times has an

I often get asked ‘how can I avoid common misunderstandings in neuroscience’ which I always think is a bit of an odd question because the answer is ‘learn a lot about neuroscience’.

I often get asked ‘how can I avoid common misunderstandings in neuroscience’ which I always think is a bit of an odd question because the answer is ‘learn a lot about neuroscience’.

A festival of music, film and neuroscience is about to kick off in an abandoned psychiatric hospital in East London. Called

A festival of music, film and neuroscience is about to kick off in an abandoned psychiatric hospital in East London. Called

Philosopher

Philosopher  One of the computational linguists who applied forensic text analysis to JK Rowling’s books to uncover her as the author of

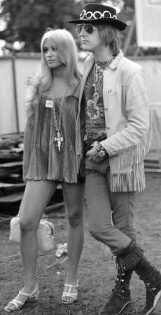

One of the computational linguists who applied forensic text analysis to JK Rowling’s books to uncover her as the author of  The Groupies is a remarkable

The Groupies is a remarkable