Today’s BPS Research Digest has a wonderfully ironic and recursive Freudian slip in a post about the misdiagnosis of women with mental illness in Victorian Britain.

Today’s BPS Research Digest has a wonderfully ironic and recursive Freudian slip in a post about the misdiagnosis of women with mental illness in Victorian Britain.

It highlights how misdiagnosis could get the doctor in hot water, and makes a link with Freud’s later ideas about hysteria – symptoms that appear to be neurological, such as paralysis, but aren’t accounted for by damage to the nervous system.

I hope Christian won’t mind me pointing out that the misspelling of Freud is brilliantly paradoxical:

Remember this is some decades before Fraud started applying the diagnosis of conversion disorder or hysteria to so many women, many of whom probably had organic illnesses.

Freud argued that the ‘Freudian slip‘, or parapraxis, is an example of the unconscious mind slipping past our conscious editing of speech and action, potentially revealing the true beliefs of desires of the person in question.

I wonder whether he’d feel vindicated over the sentence above, or would just despair that such talented psychologists think he was talking bunk on this occasion.

With regards to the question over the reliability of diagnosing hysteria, now reclassified as ‘conversion disorder‘, Slater completed a famous 1965 study where he followed up patients who had been diagnosed with hysteria to see if they later showed definite signs of neurological illness.

He found that over 60% later showed signs of genuine neurological illness and dryly stated that “The only thing that ‚Äòhysterical‚Äô patients have in common is that they are all patients”.

Although influential at the time, it has subsequently been discredited as lacking rigorous methods (taking family doctor notes as follow-up data, for example).

The most comprehensive study was published in 2005 and looked at patients diagnosed with hysteria over many decades and found that misdiagnosis rates were one third in the 1950s, but have been at 4% since the 1970s – probably due to the emergence of reliable brain imaging technologies.

Incidentally, the image on the left is a slightly edited panel from a six page comic called The New Adventures of Sigmund Freud where an Uzi toting Sigmund takes on Osama Bin Laden in his secret lair.

Link to BPSRD on ‘The Suspicions of Mr Whicher’.

Link to 2005 hysteria follow-up study with full text link.

Link to The New Adventures of Sigmund Freud.

The Atlantic has a provocative

The Atlantic has a provocative  The August edition of the Nature Neuroscience podcast, NeuroPod,

The August edition of the Nature Neuroscience podcast, NeuroPod,  The

The

The Boston Globe has an interesting

The Boston Globe has an interesting

Cognitive scientists should be explorers of the mind, forging a path through the chaotic world of everyday life before even thinking of retreating to the lab, according to a critical

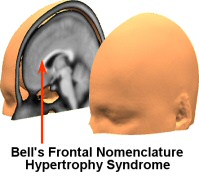

Cognitive scientists should be explorers of the mind, forging a path through the chaotic world of everyday life before even thinking of retreating to the lab, according to a critical  I have discovered shocking evidence that computers are affecting the brain. After extensive research, I have discovered the problem is remarkably specific and I have isolated it to an individual brain area affected by one particular application. Microsoft Word is causing abnormal growth in the frontal lobes.

I have discovered shocking evidence that computers are affecting the brain. After extensive research, I have discovered the problem is remarkably specific and I have isolated it to an individual brain area affected by one particular application. Microsoft Word is causing abnormal growth in the frontal lobes. The September issue of The Psychologist has two excellent and freely available articles that smash the popular myths of scientific psychology.

The September issue of The Psychologist has two excellent and freely available articles that smash the popular myths of scientific psychology.

Wikipedia has a short but fascinating

Wikipedia has a short but fascinating  Neurophilosophy has a stimulating

Neurophilosophy has a stimulating  Today’s New York Times has an interesting

Today’s New York Times has an interesting  Today’s Nature has a teeth-grittingly bitchy

Today’s Nature has a teeth-grittingly bitchy  PLoS Biology has a cozy

PLoS Biology has a cozy