Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

There’s a fantastic discussion and video interview on America’s first prison for drug addicts, “the world’s most famous – and infamous – center for the treatment and study of drug addiction”, over at Neuroanthropology.

The Guardian has a piece by psychologist Susan Blackmore on why she’s changed her mind on the idea that religion works like a ‘meme virus’.

How political beliefs affect racial biases. Neuron Culture covers an intriguing study on how both liberals and conservatives show racial biases but in opposite directions in moral reasoning tasks.

Time has a beautiful gallery of photos depicting how different types of booze look under a microscope. Brings a whole a new meaning to the term ‘beer goggles’.

The paradoxes of pharmaco-psychiatry are discussed in excellent coverage from Neuroskeptic. If you read only one piece on mental health this week, make it this one.

The Globe and Mail discuss how popularity influences how infectious diseases spread, discussing new research showing that the cool kids get the flu first .

Why are women often chosen to lead organisations in a crisis? Fascinating counter-intuitive sex bias covered by the BPS Research Digest. Bonus dispiriting last paragraph.

Science News covers a study on how video games damage the… Sorry, my mistake, it’s another study on how action video games lead to generalisable cognitive benefits.

There’s another good piece on Evidence Based Mummy about how kids’ ability with numbers is strongly linked to how often their parents talk about numbers. I love the phrase ‘number talk’.

The New York Times publish a full-on retraction for an unrealistic story about how future Alzheimer’s could be detected with 100% accuracy. The Neuroshrink blog had called bullshit two weeks ago.

The ever-excellent forensic psychology blog In the News covers another academic attack on criminal profiling as “so vague as to be meaningless”.

Wired Science covers an interesting legal bias finding, for crimes of toxin exposure, more severe punishments are handed out for crimes with fewer victims.

I found an interesting video on YouTube where a self-identified face-taste synaesthete describes what tastes different famous faces evoke. No Shakira, but I suspect her face tastes like a choir of angels weeping gently on your tongue.

The LA Times on how endocrinologists are calling out two widely discussed conditions without a medical basis, ‘adrenal fatigue’ and ‘Wilson’s temperature fatigue’, as “internet diseases”. I suspect, without knowing what internet disease is slang for.

The Oxford English Dictionary now has a definition taken from Language Log immediately opening a recursion hole in the fabric of space and time.

University of Texas press release on a study finding that placebo improves ‘low sexual functioning’ in 1-in-3 women. “For more information, contact: Jessica Sinn”

A new study on how modern psychosurgery lifts mood in chronically depressed patients is covered by The Neurocritic.

The Sydney Morning Herald covers a study on how people who are better at introspection have structural differences in the anterior prefrontal cortex.

There’s a podcast discussion with neuroscience-inspired artist Garry Kennard over at The Beautiful Brain.

VBS.TV has a fantastic interview with Alexander Shulgin, psychedelic chemist and researcher extraordinaire.

There’s a fantastic piece on how we unintentionally ‘mirror’ other people’s speech patterns during conversation over at Sensory Superpowers.

BoingBoing interviews the Perez Hilton of Mexico’s drug war – the anonymous writer behind Blog De Narco.

There are 10 psychological insights into online dating taken from the scientific literature over at PsyBlog.

Discover Magazine has an opinion piece by tech psychologist Sherry Turkle on her vision for the near future of human society.

Can we all become delusional with hypnosis? Brief but good piece by philosopher Lisa Bortolotti on The Splintered Mind.

Seed Magazine has an intriguing piece on the psychoactive effects of food.

Perceptual and perceptive psychologist Mark Changizi guest posts on PLoS Blogs about a proposal for the ‘Red Club for Men’.

The Cold War espionage styles of the US and Soviet spy agencies are compared in a fantastic article for the history of science journal Isis that notes that while the Americans tended to invest in technology, the Russians were more focused on ‘human intelligence’.

The Cold War espionage styles of the US and Soviet spy agencies are compared in a fantastic article for the history of science journal Isis that notes that while the Americans tended to invest in technology, the Russians were more focused on ‘human intelligence’.

The New York Times has an excellent

The New York Times has an excellent

The Yale Alumni Magazine has a moving and beautifully written

The Yale Alumni Magazine has a moving and beautifully written

The Atlantic has an amazing

The Atlantic has an amazing

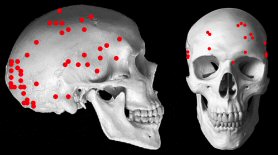

Gunshot wounds to the head are a major cause of death among soldiers in combat but little is known about where bullets are more likely to impact. A

Gunshot wounds to the head are a major cause of death among soldiers in combat but little is known about where bullets are more likely to impact. A

The Twilight series of young adult novels “could be affecting the dynamic workings of the teenage brain in ways scientists don’t yet understand” according to a bizarre

The Twilight series of young adult novels “could be affecting the dynamic workings of the teenage brain in ways scientists don’t yet understand” according to a bizarre