A mysterious epidemic of paralysis was sweeping through 1920s America that had the medical community baffled. The cause was first identified not by physicians, but by blues singers.

A mysterious epidemic of paralysis was sweeping through 1920s America that had the medical community baffled. The cause was first identified not by physicians, but by blues singers.

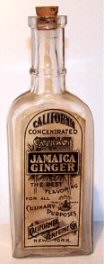

During the prohibition, alcohol was banned but people got buzzed the best way they could. One way was through a highly alcoholic liquid called Jamaica Ginger or ‘Jake’ that got round the ban by being sold as a medicine.

Eventually the feds caught on and even such poorly disguised medicines were blacklisted but Jamaica Ginger stayed popular, and alcoholic, due to the producers including an organophosphate additive called tricresyl phosphate that helped fool the government’s tests.

What they didn’t know was that tricresyl phosphate is a slow-acting neurotoxin that affected the neurons that control movement.

The toxin starts by causing lower leg muscular pain and tingling, followed by muscle weakness in the arms and legs. The effect on the legs caused a distinctive form of muscle paralysis that required affected people to lift the leg high during walking to allow the foot to clear the ground.

This epidemic of paralysis first made the pages of the New England Journal of Medicine in June 1930, but the cause remained a mystery.

What the puzzled doctors didn’t know was that the cause had been identified by two blues musicians earlier that year, in songs released on 78rpm records.

Ishman Bracey’s song Jake Liquor Blues and Tommy Johnson’s track Alcohol and Jake Blues had hit on the key epidemiological factor, the consumption of Jamaica Ginger, likely due to their being part of the poor southern communities where jake was most commonly drunk.

Slowly, the medical community caught on, noting that the additive damaged the spinal cord and peripheral nerves, and the adulterated jake was slowly tracked down and outlawed.

The story, however, has an interesting neurological twist. In 1978, two neurologists decided to track down some of the survivors of jake poisoning 47 years after the booze fuelled epidemic hit.

They found that the original neurological explanation for the ‘jake walk’ effect was wrong. The paralysis was actually due to damage to the movement control neurons in the brain (upper motor neurons) and not the peripheral nervous system.

Jake was much more dangerous than thought and the false lead was probably due to inadequate assessments when the epidemic hit, possibly because the stigma associated with the condition prevented a thorough investigation.

The study has a poignant description of the social effect of the condition:

The shame experienced by those with jake leg possibly led some with a minimal functional disorder to deny that they ever had the disease, and patient 4 stated that he knew some such people. We heard of other men with obvious impairment who claimed to have had a stroke.

If you want to read more on this curious piece of neurological there’s a great article on Providentia you can check out for free and a renowned 2003 article from The New Yorker which is locked behind a paywall due to digital prohibition.

Link to Providentia post on Ginger Jake.

Medical History has a brief but good article on the political wranglings and scientific battles between psychiatry, psychoanalysis and clinical psychology in 20th Century America.

Medical History has a brief but good article on the political wranglings and scientific battles between psychiatry, psychoanalysis and clinical psychology in 20th Century America.

The Glass Piano is a wonderful BBC Radio 3

The Glass Piano is a wonderful BBC Radio 3

If pant-wetting were a sport, the recent

If pant-wetting were a sport, the recent  It’s been forty years since the Stanford prison experiment and the university’s alumni magazine has asked the participants and researchers for their

It’s been forty years since the Stanford prison experiment and the university’s alumni magazine has asked the participants and researchers for their  The July issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry has another

The July issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry has another  A mysterious epidemic of paralysis was sweeping through 1920s America that had the medical community baffled. The cause was first identified not by physicians, but by blues singers.

A mysterious epidemic of paralysis was sweeping through 1920s America that had the medical community baffled. The cause was first identified not by physicians, but by blues singers. A curious anecdote about legendary neurologist

A curious anecdote about legendary neurologist  The New York Times has an extended

The New York Times has an extended

The Providentia blog has a brilliant

The Providentia blog has a brilliant