A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed.

A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed.

Broca’s area was one of the first brain areas identified with a specific function after 19th Century neurologist Paul Broca autopsied a man who had lost the ability to speak.

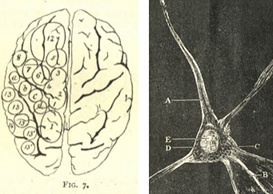

When examining the man’s brain (you can see it on the right), Broca found selective damage to the third convolution of the left frontal lobe and linked this with the fact that the person could understand speech but not produce it.

This type of speech problem after brain injury is now known as Broca’s aphasia but his innovation was not simply naming a new type of neurological problem.

Broca was one of the first people to think of the brain in terms of separate areas supporting specialised functions and studying patterns of difficulty after brain damage as a way of working this out – a science now known as cognitive neuropsychology.

The patient Broca described was nicknamed ‘Tan’ because this was the only syllable he could produce. The scientific report named his as Monsieur Leborgne but no further details existed.

Oddly, personal details were not even recorded in Broca’s unpublished medical notes for the patient.

Because of the mystery, people have speculated for years about the identity of Monsieur Leborgne with theories ranging from the idea that he was a French peasant to a philandering man struck down by syphilis.

But now, historian Cezary Domanski has tracked down the identity of Broca’s famous patient through detective work in record offices in France and published the results in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences.

According to the Broca’s report, the health problems of Louis Victor Leborgne became apparent during his youth, when he suffered the first fits of epilepsy. Although epileptic, Louis Victor Leborgne was a working person. He lived in Paris, in the third district. His profession is given as “formier” (a common description in the nineteenth century used for craftsmen who produced forms for shoemakers).

Leborgne worked until the age of 30 when the loss of speech occurred. It is not known if the damage to the left side of Leborgne’s brain had anything to do with traumas sustained during fits of epilepsy nor, as reported in some recent publications, does it appear to have been caused by syphilis, as that was not indicated in Broca’s reports. The immediate cause for his hospitalization was his problem with communicating.

Leborgne was admitted to the Bicêtre hospital two or three months after losing his ability to speak. Perhaps at first this might have been perceived as a temporary loss, but the defect proved incurable. Because Leborgne was unmarried, he could not be released to be cared for by close relatives; he therefore spent the rest of his life (21 years total) in the hospital.

Domanski’s article finishes on a poignant note, highlighting that Leborgne became famous through his disease and death and his life history was seemingly thought irrelevant even when he was alive.

“It is time” says Domanski, “for Louis Victor Leborgne to regain his identity”.

Link to locked article on the identity of Broca’s patient (via @Neuro_Skeptic)

The New York Review of Books has a reflective piece by Oliver Sacks on the swirling mists of memory and how false recall has affected authors and artists throughout history.

The New York Review of Books has a reflective piece by Oliver Sacks on the swirling mists of memory and how false recall has affected authors and artists throughout history. A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed.

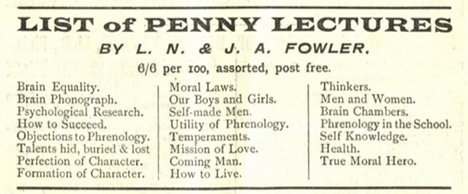

A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed. The images on the right are from the June 1890 edition (the brain) and October 1895 edition (the neuron) and both show some of the then cutting-edge neuroscience that the magazine regularly featured.

The images on the right are from the June 1890 edition (the brain) and October 1895 edition (the neuron) and both show some of the then cutting-edge neuroscience that the magazine regularly featured.

Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist

Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist

A familiar sight amid the Christmas supermarket shelves is the box of Black Magic chocolates. It’s a classic product that’s been familiar to British shoppers since the 1930s but less well known is the fact that it was entirely designed by psychologists.

A familiar sight amid the Christmas supermarket shelves is the box of Black Magic chocolates. It’s a classic product that’s been familiar to British shoppers since the 1930s but less well known is the fact that it was entirely designed by psychologists.

The Global Mail has an amazing

The Global Mail has an amazing  Alistair Cooke presented the longest running radio show in history. The BBC’s Letter from America was a

Alistair Cooke presented the longest running radio show in history. The BBC’s Letter from America was a

A fascinating short excerpt from a new

A fascinating short excerpt from a new  “It’s no secret” says the promotional material “that several professional footballers live in Repton Park”, presumably unaware that one of London’s most luxurious housing developments used to be a psychiatric hospital.

“It’s no secret” says the promotional material “that several professional footballers live in Repton Park”, presumably unaware that one of London’s most luxurious housing developments used to be a psychiatric hospital.

Novelist

Novelist  The Lancet has a wonderful

The Lancet has a wonderful