I’ve just bought an excellent book called Invention of Hysteria which is about how the use of photography by the 19th century French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot helped shape the our concepts of ‘hysteria‘ – a disorder where psychological disturbances manifest themselves as what seem like neurological symptoms.

I’ve just bought an excellent book called Invention of Hysteria which is about how the use of photography by the 19th century French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot helped shape the our concepts of ‘hysteria‘ – a disorder where psychological disturbances manifest themselves as what seem like neurological symptoms.

Such patients would today be diagnosed with ‘conversion disorder’, usually after presenting to a neurology clinic with paralysis, blindness or epilepsy, only for it to be found that there is no damage to any of the areas you might expect or no seizure activity in the brain during a ‘fit’.

Importantly, the patients aren’t ‘faking’, they genuinely experience themselves as paralysed, blind, or otherwise impaired.

What recent research suggests is that there may be a disturbance in higher level brain function which may be suppressing normal actions or sensation.

To use a business analogy, none of the workers are on strike but the management is causing problems so the work can’t be carried out.

Charcot revived interest in this disorder through his weekly, somewhat theatrical, case demonstrations, and, as the book discusses, through some striking and equally theatrical photos and illustrations.

This wonderfully illustrated book examines the history of Charcot’s work at the Salp√™tri√®re, the famous Paris hospital, and how the newly developed technology of photography played a key role in popularising the disorder and shaping our ideas about hysteria.

In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, the Salpêtrière was what it had always been: a kind of feminine inferno, a citta dolorosa confining four thousand incurable or mad women. It was a nightmare in the midst of Paris’s Belle Epoque.

This is where Charcot rediscovered hysteria. I attempt to retrace how he did so, amidst all the various clinical and experimental procedures, through hypnosis and the spectacular presentations of patients having hysterical attacks in the amphitheater where he held his famous Tuesday Lectures. With Charcot we discover the capacity of the hysterical body, which is, in fact, prodigious. It is prodigious; it surpasses the imagination, surpasses “all hopes,” as they say.

Whose imagination? Whose hopes? There’s the rub. What the hysterics of the Salpêtrière could exhibit with their bodies betokens an extraordinary complicity between patients and doctors, a relationship of desires, gazes, and knowledge. This relationship is interrogated here.

What still remains with us is the series of images of the Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. It contains everything: poses, attacks, cries, “attitudes passionnelles,” “crucifixions,” “ecstasy,” and all the postures of delirium. If everything seems to be in these images, it is because photography was in the ideal position to crystallize the link between the fantasy of hysteria and the fantasy of knowledge.

A reciprocity of charm was instituted between physicians, with their insatiable desire for images of Hysteria, and hysterics, who willingly participated and actually raised the stakes through their increasingly theatricalized bodies. In this way, hysteria in the clinic became the spectacle, the invention of hysteria. Indeed, hysteria was covertly identified with something like an art, close to theater or painting.

The book’s website has the first chapter freely available, but sadly none of the photos.

The book’s website has the first chapter freely available, but sadly none of the photos.

Most of Charcot’s books, containing many of the wonderful illustrations and photos, are listed on Google Books but for some reason I can’t work out, you can’t view the pages.

As they were published in the late 1800s, they should be well out of copyright, so its a bit frustrating we can’t read them.

To give you an idea, however, the illustration on the left is the ‘Grande Hysterie Full Arch’, one of Charcot’s classifications of hysterical epilepsy.

This is one of Charcot’s many illustrations of amazing bodily contortions that was used as inspiration by the famed and somewhat eccentric French sculptor Louise Bourgeois, as you can see in a (possibly NSFW?) article on her work from the Tate magazine.

Link to details of book with sample chapter.

Neurophilosophy has found a fascinating black and white TV documentary on Mexican hallucinogenic mushrooms from 1961, where the presenter samples some of the psilocybin-containing fungus and reports the effects during the trip.

Neurophilosophy has found a fascinating black and white TV documentary on Mexican hallucinogenic mushrooms from 1961, where the presenter samples some of the psilocybin-containing fungus and reports the effects during the trip. Time

Time

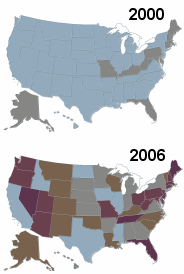

After a number of investigations into the under-disclosure of drug industry earnings by top psychiatry researchers, The New York Times

After a number of investigations into the under-disclosure of drug industry earnings by top psychiatry researchers, The New York Times  In early July, London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts hosted three nights of punk rock chaos with a difference, some of the audience were artificially intelligent

In early July, London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts hosted three nights of punk rock chaos with a difference, some of the audience were artificially intelligent  DrugMonkey has

DrugMonkey has

I’ve just bought an excellent

I’ve just bought an excellent  The book’s website has the first chapter freely available, but sadly none of the photos.

The book’s website has the first chapter freely available, but sadly none of the photos. PsyBlog has collected the

PsyBlog has collected the  PsychCentral, one of the original internet psychology sites, has recently been

PsychCentral, one of the original internet psychology sites, has recently been

PsyBlog has asked readers to

PsyBlog has asked readers to  The papers are full of

The papers are full of  Popular psychology magazine Psychology Today have launched their own

Popular psychology magazine Psychology Today have launched their own  ‘Who says Americans don’t do irony?’ I

‘Who says Americans don’t do irony?’ I  Homosexuality is a mental illness, at least according to the head of Northern Ireland’s health committee. Iris Robinson MP, who, with impeccable timing, put forth her

Homosexuality is a mental illness, at least according to the head of Northern Ireland’s health committee. Iris Robinson MP, who, with impeccable timing, put forth her