Yesterday’s Nature contains an intriguing short report of how stimulating part of the brain during neurosurgery induced the feeling that a shadowy version of the patient’s body had appeared and was mirroring the patient’s movements.

Yesterday’s Nature contains an intriguing short report of how stimulating part of the brain during neurosurgery induced the feeling that a shadowy version of the patient’s body had appeared and was mirroring the patient’s movements.

The patient was undergoing routine neurosurgery to examine the brain, prior to more serious neurosurgery to treat otherwise untreatable epilepsy.

It is not uncommon for patients to volunteer to take part in simple neuroscience experiments during these procedures.

Patients have to be awake for part of the neurosurgery anyway because the surgeons probe the brain to make sure they avoid removing any areas essential for language, memory and so on.

The experience of feeling or seeing a double or your own body is called autoscopy or heautoscopy.

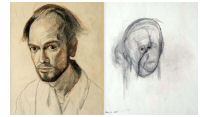

In this case, a team of researchers led by neuroscientist Shahar Arzy managed to induce this experience by stimulating an area of the brain called the left temporoparietal junction.

This is the area on the left side of the brain where the temporal lobe and parietal lobe meet (see the pink arrow in the image on the left).

This is not the first case of this kind. The Nature report is from the lab of Olaf Blanke which has reported a number of cases of this condition, either owing to brain injury, epilepsy, or induced by brain stimulation.

In a 2004 paper published in Brain, Blanke’s team reported on a number of patients who experienced this phenomenon, including one who said “I see myself lying in bed, from above, but I only see my legs” when her brain was also stimulated in the left temperoparietal junction.

In a further recent paper published in Cortex, Peter Brugger and colleagues reviewed 14 cases of ‘polyopic heautoscopy’, where patients experience multiple doubles of their own body.

(NB: This paper is available on Cortex’s website but because their site is such as mess, you can’t link to it directly and you have to use Explorer to navigate. Isn’t progress great?)

The temporoparietal junction might be significant as it is thought to process and hold representations of the body and its relationship to external space.

One interesting aspect of the Nature paper is that the patient reported that her double was unpleasant and seemed to have somewhat malign intentions:

Further stimulations (11.0 mA; n=2) were applied while the seated patient performed a naming (language-testing) task using a card held in her right hand: she again reported the presence of the sitting “person”, this time displaced behind her to her right and attempting to interfere with the execution of her task (“He wants to take the card”; “He doesn‚Äôt want me to read”).

The authors suggest they may have found evidence for the mechanism behind ‘delusions of control’ or ‘passivity symptoms’ usually linked to schizophrenia.

These are experiences or beliefs that the body and / or mind is being controlled by external forces.

However, not all patients with autoscopy report their experiences as malign, and it may be that the effect of the anaesthetics (known to induce paranoia in some), epilepsy (also linked to risk for psychosis) or the stress of the operation, may have given an unpleasant or malign twist to the experience which might not be directly linked to the disruption of the proposed brain mechanism itself.

The paper is also discussed on Nature’s news service.

Link to abstract of Nature study.

Link to Nature News write-up.

Link to full-text of 2004 Brain paper.

Link to full-text of Journal of Neuroscience paper on tempororparietal junction, body image and self .

The New York Times has

The New York Times has  The graph on the left shows EEG recordings taken from the temporal lobes during a period of speaking in tongues that show increased ‘spike events’.

The graph on the left shows EEG recordings taken from the temporal lobes during a period of speaking in tongues that show increased ‘spike events’. The Washington Post investigates the neuroscience of lying in a recent

The Washington Post investigates the neuroscience of lying in a recent  I went to the

I went to the

Seed Magazine

Seed Magazine  The Times has a

The Times has a  Brain Ethics has a fantastic

Brain Ethics has a fantastic  The

The  Science News

Science News

Yesterday’s Nature contains an intriguing

Yesterday’s Nature contains an intriguing  The University of Wisconsin Medical School have an online

The University of Wisconsin Medical School have an online  There’s a useful

There’s a useful