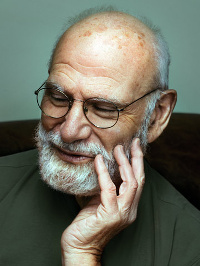

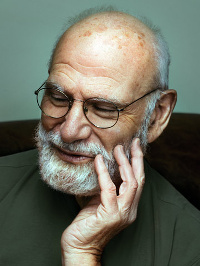

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks has died at the age of 82.

Neurologist and author Oliver Sacks has died at the age of 82.

It’s hard to fully comprehend the enormous impact of Oliver Sacks on the public’s understanding of the brain, its disorders and our diversity as humans.

Sacks wrote what he called ‘romantic science’. Not romantic in the sense of romantic love, but romantic in the sense of the romantic poets, who used narrative to describe the subtleties of human nature, often in contrast to the enlightenment values of quantification and rationalism.

In this light, romantic science would seem to be a contradiction, but Sacks used narrative and science not as opponents, but as complementary partners to illustrate new forms of human nature that many found hard to see: in people with brain injury, in alterations or differences in experience and behaviour, or in seemingly minor changes in perception that had striking implications.

Sacks was not the originator of this form of writing, nor did he claim to be. He drew his inspiration from the great neuropsychologist Alexander Luria but while Luria’s cases were known to a select group of specialists, Sacks wrote for the general public, and opened up neurology to the everyday world.

Despite Sacks’s popularity now, he had a slow start, with his first book Migraine not raising much interest either with his medical colleagues or the reading public. Not least, perhaps, because compared to his later works, it struggled to throw off some of the technical writing habits of academic medicine.

It wasn’t until his 1973 book Awakenings that he became recognised both as a remarkable writer and a remarkable neurologist, as the book recounted his experience with seemingly paralysed patients from the 1920s encephalitis lethargica epidemic and their remarkable awakening and gradual decline during a period of treatment with L-DOPA.

The book was scientifically important, humanely written, but most importantly, beautiful, as he captured his relationship with the many patients who experienced both a physical and a psychological awakening after being neurologically trapped for decades.

It was made into a now rarely seen documentary for Yorkshire Television which was eventually picked up by Hollywood and made into the movie starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro.

But it was The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat that became his signature book. It was a series of case studies, that wouldn’t seem particularly unusual to most neurologists, but which astounded the general public.

A sailor whose amnesia leads him to think he is constantly living in 1945, a woman who loses her ability to know where her limbs are, and a man with agnosia who despite normal vision can’t recognise objects and so mistook his wife’s head for a hat.

His follow-up book An Anthropologist on Mars continued in a similar vein and made for equally gripping reading.

Not all his books were great writing, however. The Island of the Colorblind was slow and technical while Sacks’s account of how his damaged leg, A Leg to Stand On, included conclusions about the nature of illness that were more abstract than most could relate to.

But his later books saw a remarkable flowering of diverse interest and mature writing. Music, imagery, hallucinations and their astounding relationship with the brain and experience were the basis of three books that showed Sacks at his best.

And slowly during these later books, we got glimpses of the man himself. He revealed in Hallucinations that he had taken hallucinogens in his younger years and that the case of medical student Stephen D in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat – who developed a remarkable sense of smell after a night on speed, cocaine, and PCP – was, in fact, an autobiographical account.

His final book, On the Move, was the most honest, as he revealed he was gay, shy, and in his younger years, devastatingly handsome but somewhat troubled. A long way from the typical portrayal of the grey-bearded, kind but eccentric neurologist.

On a personal note, I have a particular debt of thanks to Dr Sacks. When I was an uninspired psychology undergraduate, I was handed a copy of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat which immediately convinced me to become a neuropsychologist.

Years later, I went to see him talk in London following the publication of Musicophilia. I took along my original copy of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, hoping to surprise him with the news that he was responsible for my career in brain science.

As the talk started, the host mentioned that ‘it was likely that many of us became neuroscientists because we read Oliver Sacks when we started out’. To my secret disappointment, about half the lecture hall vigorously nodded in response.

The reality is that Sacks’s role in my career was neither surprising nor particularly special. He inspired a generation of neuroscientists to see brain science as a gateway to our common humanity and humanity as central to the scientific study of the brain.

Link to The New York Times obituary for Oliver Sacks.

While you’re visiting, by the way, have a walk through the hospital grounds. They’re open to the public, extensive and beautiful. Locals walk their dogs there and come in the use the swimming pool. It’s quite different from how many people imagine a psychiatric hospital to be (and it has to be said, quite different from how many other psychiatric hospitals are).

While you’re visiting, by the way, have a walk through the hospital grounds. They’re open to the public, extensive and beautiful. Locals walk their dogs there and come in the use the swimming pool. It’s quite different from how many people imagine a psychiatric hospital to be (and it has to be said, quite different from how many other psychiatric hospitals are).

The

The